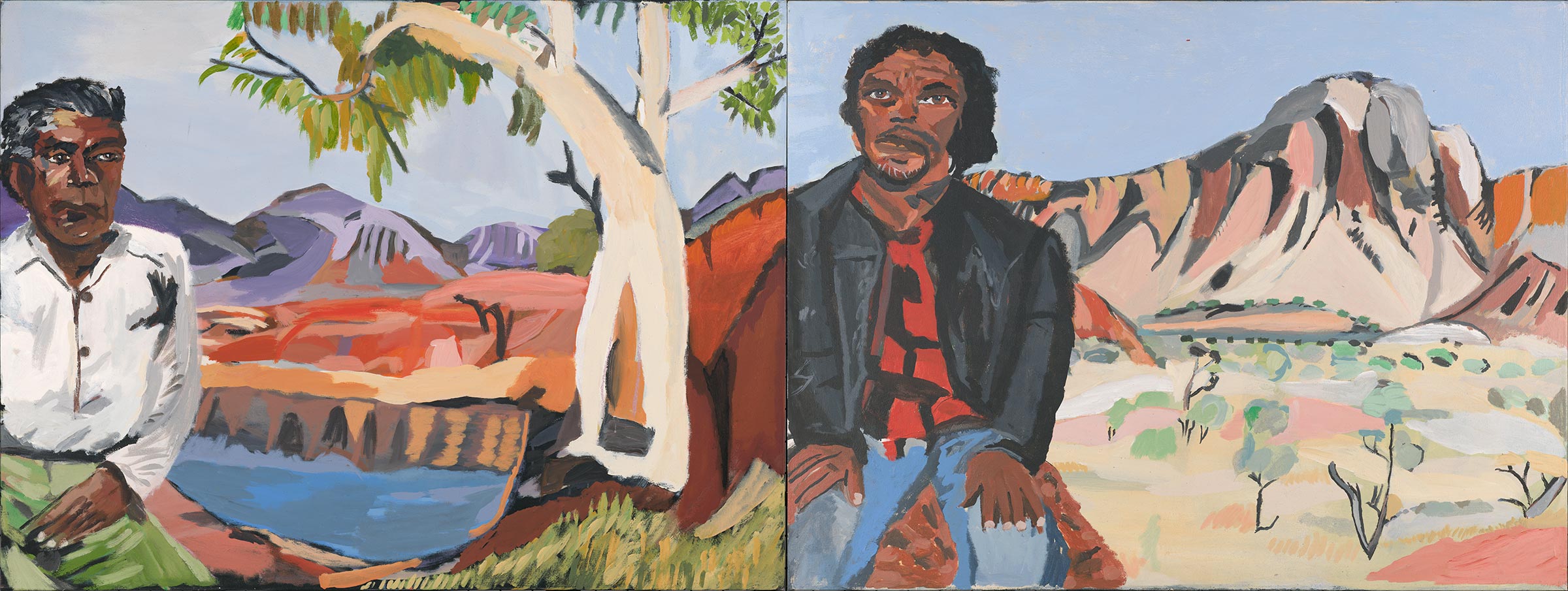

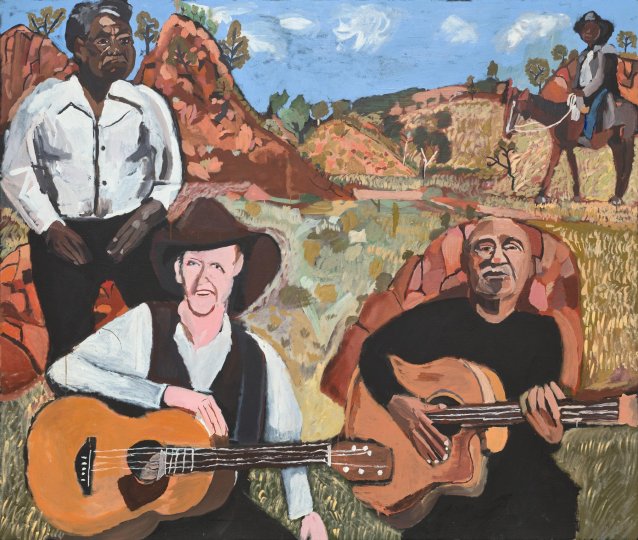

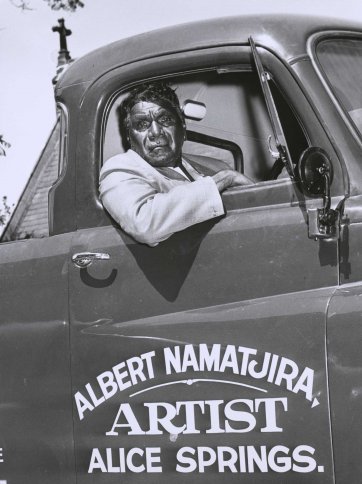

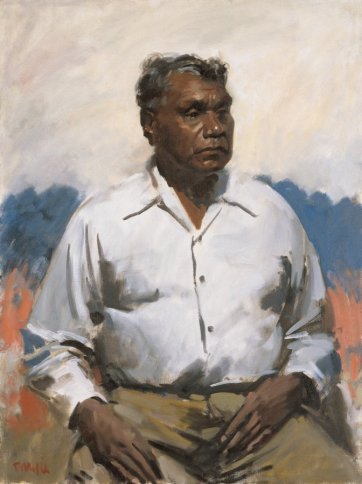

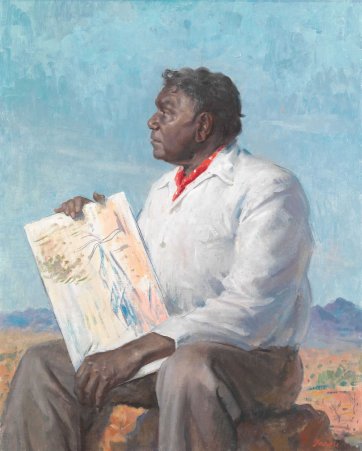

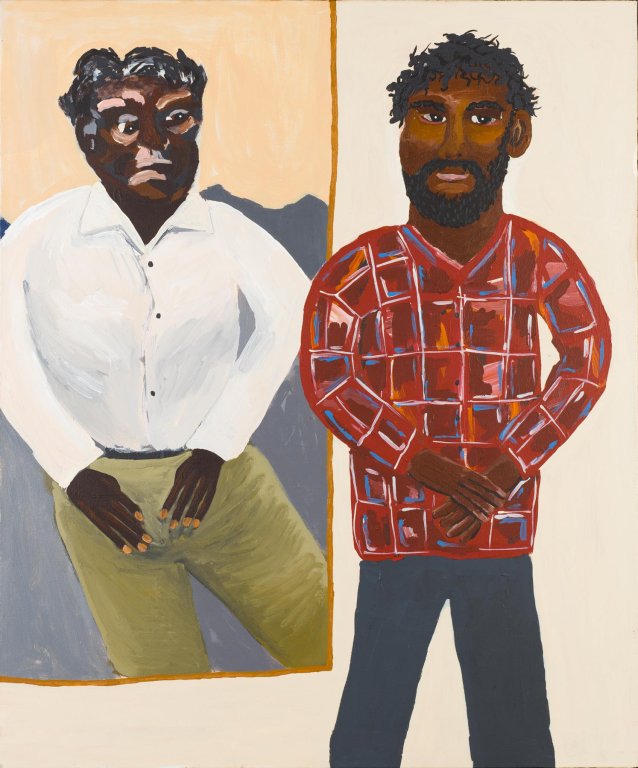

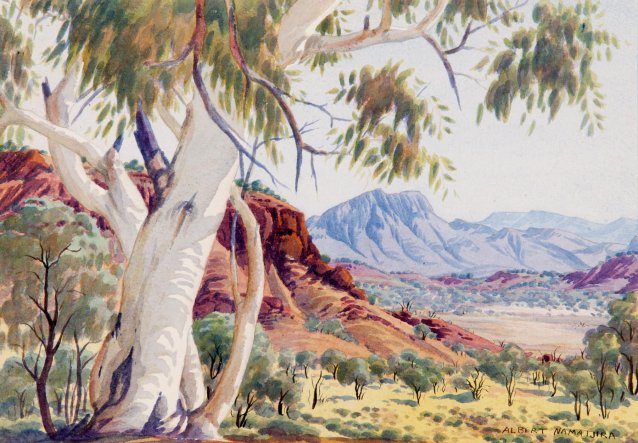

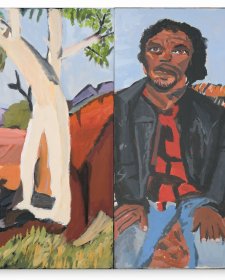

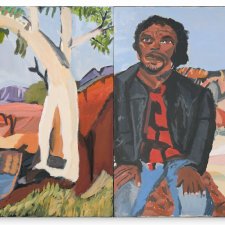

In Vincent Namatjira’s Albert and Vincent (2024), two artists converge in time and space to tell a story of legacy set against the complex histories of colonisation in Australia. The Western Aranda artist painted himself and his great-grandfather, celebrated Western Arrernte/Aranda/Arrarnta artist Albert Namatjira, before the brilliant colours and ancient rock formations of their Country near Ntaria/Hermannsburg in the Northern Territory. The collapsing of chronologies that allows the artists to sit side-by-side as an echo, a doubling, is a disruptive methodology, synchronous with the First Nations concept of the Everywhen: the co-existence of past, present and future.

‘Albert Namatjira’s legacy lives on in the power of his art and in the work of his descendants,’ Vincent wrote in his 2023 book Vincent Namatjira: Australia in colour. ‘The old man was a teacher, passing on his talents and ideas to his family. When I research Albert Namatjira’s life, when I look at his work and when I paint our Country myself, I can feel him teaching me too and I feel at peace.’

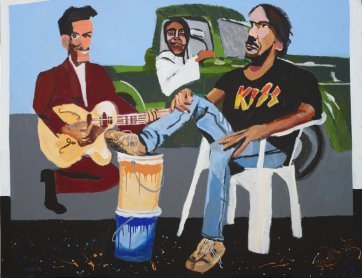

Vincent was born in Mparntwe/Alice Springs but grew up in foster care with his sister in Boorloo/Perth. He returned to Ntaria/Hermannsburg at 18, reconnecting with family, language, culture and Country. For over 10 years he has painted from Iwantja Arts in Indulkana, on Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands, South Australia. The dynamic art centre is home to fellow artists including Betty Muffler, Kaylene Whiskey and Tiger Yaltangki, and it is here that Vincent met his father-in-law, Yankunytjatjara figurative painter Kunmanara (Jimmy) Pompey, who was an important influence on the young artist. In 2020, Vincent became the first Aboriginal artist to win the Archibald Prize in its then-99-year history with his portrait of former AFL player Adam Goodes. He is one of only 32 First Nations artists who have exhibited in the prize, the first of whom was Robert Campbell Jnr in 1989.