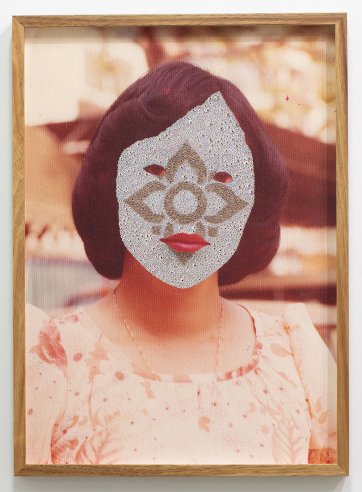

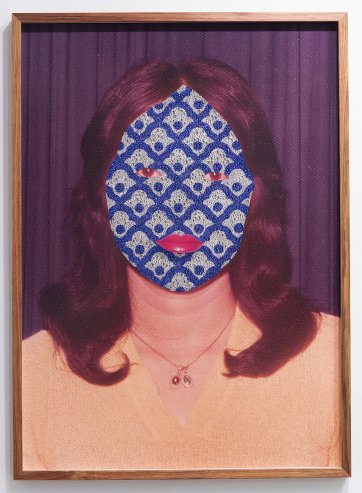

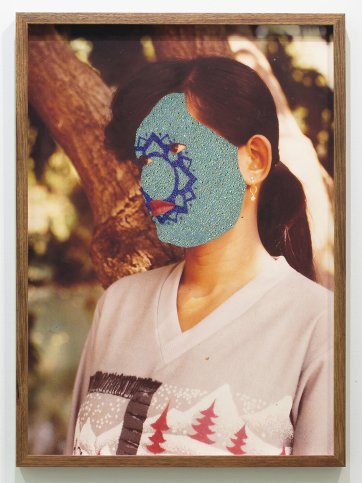

A riot of colour and floral exuberance, the National Portrait Gallery collection show In Bloom reveals complex examinations of ecology, colonisation, abundance and queerness within the realms of portraiture. Flowers have long been used as symbols to convey messages of personal, cultural and religious significance. Within floriography, or the language of flowers, each flower has its own meaning, which can also be influenced by its variety, colour and quantity.

In Bloom explores how floral symbolism is used in portaiture as a marker of identity. Traversing much-loved and lesser-known collection works both historical and contemporary alongside a selection of key loans, In Bloom features socialites, chefs, musicians, actors, doctors, politicians and artists unified by their accompanying floral markers.

One of the key themes in the exhibition is the tension between the perceived binaries of the ‘natural’ versus the ‘unnatural’, employed by artists to complicate notions of ‘otherness’ and place. Accordingly, endemic and introduced plants and flowers are used by artists to interrogate our relationships to the land and to explore broader themes of migration and the diasporic experience.

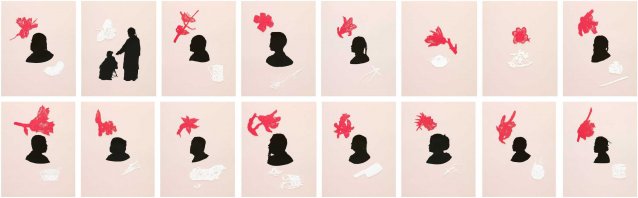

Thailand’s national plant, Thai orchids, for example, are used by Nathan Beard throughout his practice as a cultural signifier to interrogate notions of value and the slipperiness of his own Australian-Thai heritage. In Making Chinese shadows (sixteen silhouette portraits), Chinese-Australian artist Pamela See uses totemic flower papercuts as an allegory for the migrant experience. And Sāmoan artist Angela Tiatia literally consumes the Western stereotype of the sexually alluring ‘dusky maiden’ by devouring an entire hibiscus in her moving image work Hibiscus rosa sinensis.