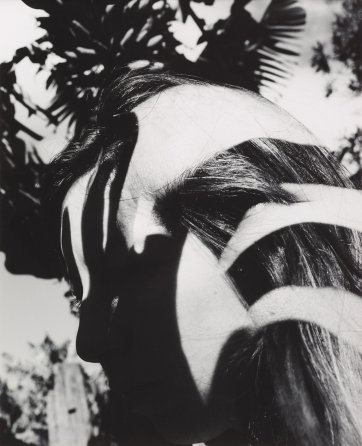

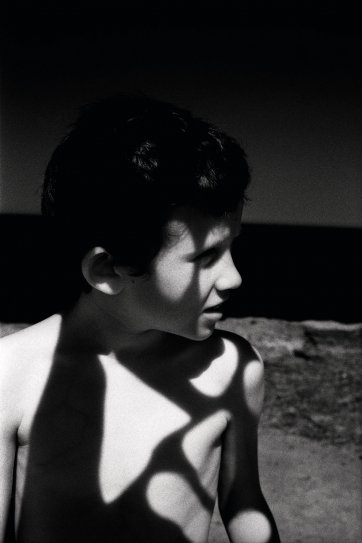

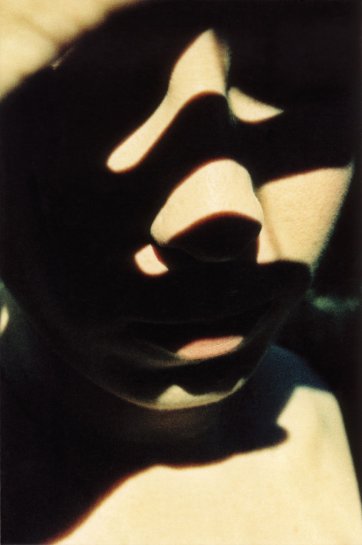

So, conceptually, this feeds into this idea of connection and disconnectedness that you explore in your artistic practice, particularly in your Korora series where we see deep shadows impressed on the figure. You talk about these shadows forming their own language system?

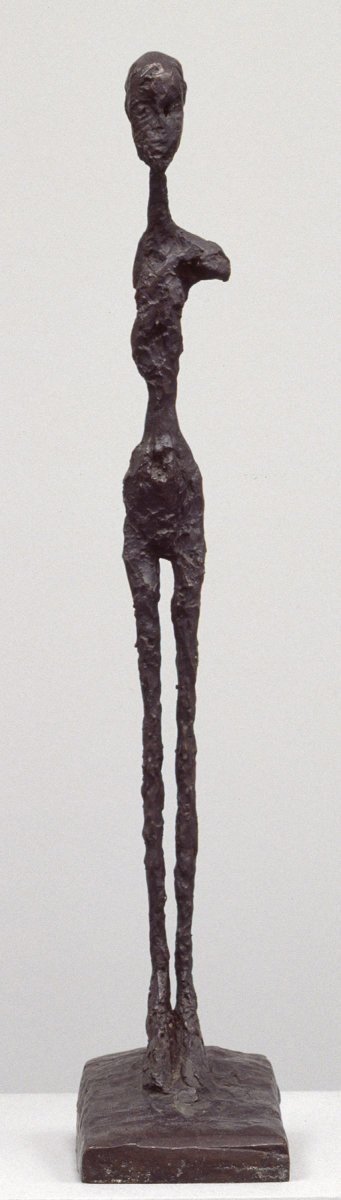

Yes, it’s almost just about considering the elemental nature of authorship that the artist is able to exploit to create and communicate when using raw materials. In Giacometti’s work, even though his sculptures haven’t been carved, you could almost mistakenly think he started with a dense block of material and carved a figure out of it, but then he’s just gone a bit too far and carved it a bit too much and it’s gone a bit too skinny. And I really like how with photography you can mask things out; you can mask out shadows, and it’s almost like you’re carving out from a block. By intervening with introduced shadows and other elements you’re more intimately creating and authoring your pictures. Inevitably when I’m in this frame of mind I like to consider that I’m photographing a presence by obscuring it and putting in a field of contradictions of hard shadows and bright highlights ... and they’re almost broken off and floating in these dark voids. I just think that’s really interesting – to create almost a constellation or a field of forms that interconnect, and then create something so abstracted.

I’d like to tap into your interest in the peripheral and this sense of weightlessness in your work.

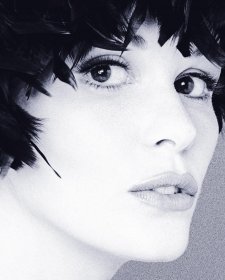

A past exhibition of mine was titled Peripheral Canopy. That title was a reference to a feeling of seeing a face, likeness or figure on the edge of vision, and purposefully not looking at it directly. I was interested in exploring what could be garnered from a presence if it were only looked at in an abstracted way, and felt in other ways. How the initial impression of a person on the periphery could be intuitively kind of absorbed. Portraits I’ve made with that in mind have been obscured with shadows reducing them to fields of isolated highlights where I’m trying to recreate a sense of something I’ve seen in my imagination. Under a dense tree canopy back home at the property where I grew up in Korora near Coffs Harbour – it was there where I spent so much time, and I began imagining apparitions amid the dappled light which were hard for me to define.

We often see outsider settings and spaces on the perimeter in your work. Can you elaborate on how your choice of environment places emphasis on the figure?

I feel as though there’s a certain balance to settings which feel non-idyllic or nondescript – they become kind of neutral texture in a picture. They also come from being a kid hanging out in vacant lots, smashing up a burned out old car, skateboarding and just fiddling around!

How does your conceptual practice feed into your commercial work?

In my personal work and to an extent in my commercial pictures I work with the malleability of reality. I let colours shift, and over or underexpose film so it gives a distressed, otherworldly look to the gradation of colours, or distorts the grain and details. In my commercial work I like working with a deadpan way of taking pictures in that the communication of the images can be clear, with ‘everyday’ scenes. That deadpan mode (or what it means to me) has only recently entered my personal work as a new way of seeing. [It’s about] documenting something significant to me with as much straightforward clarity as I can achieve. I try to get away with aspects of my personal work entering my pictures for brands and editorials, which can be fun to play with. The two ways of working kind of coexist in an awkward kind of a way. It’s a fun internal dialogue in that I can inject a little of my personal language into my commercial work without it necessarily being noticed.