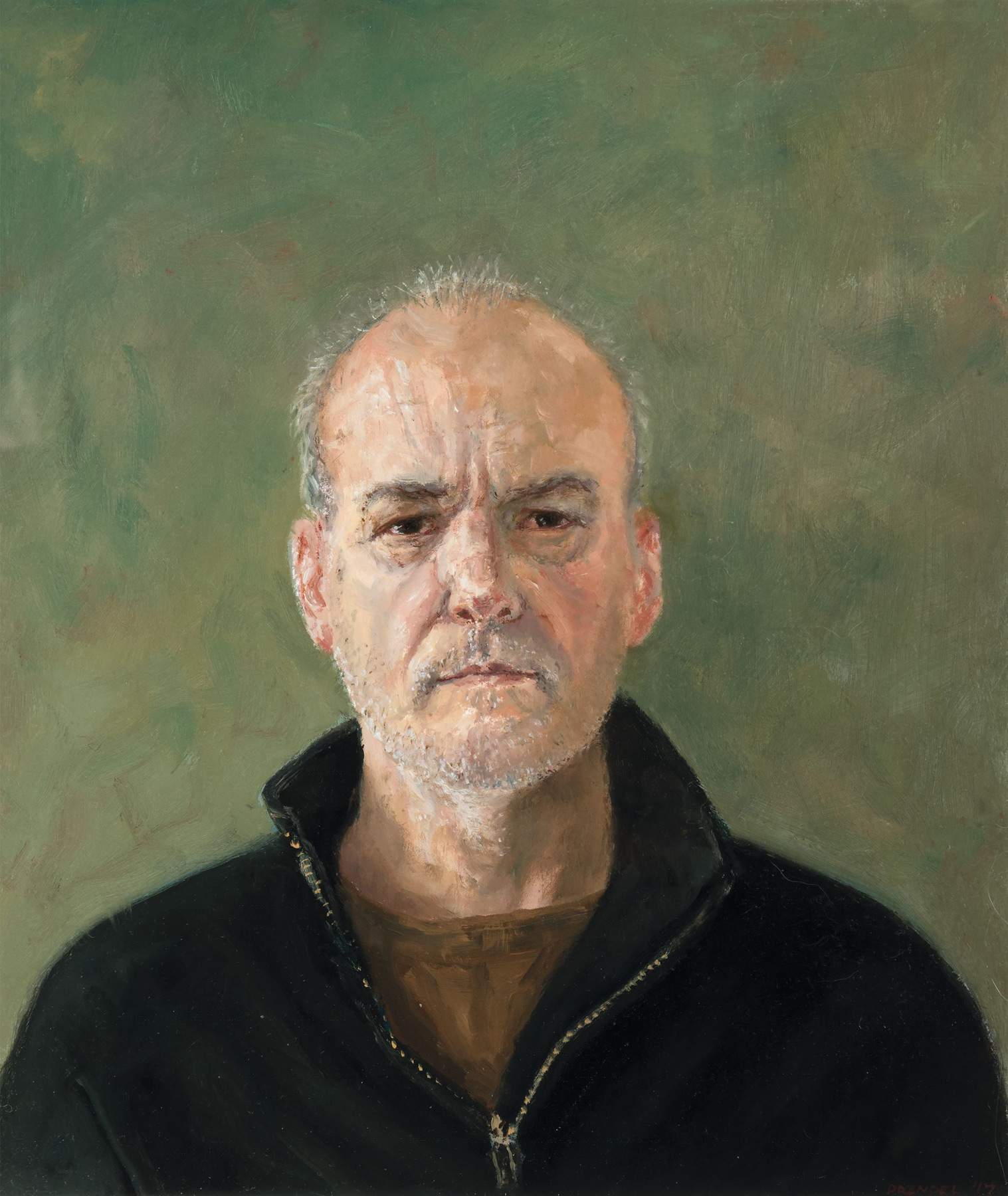

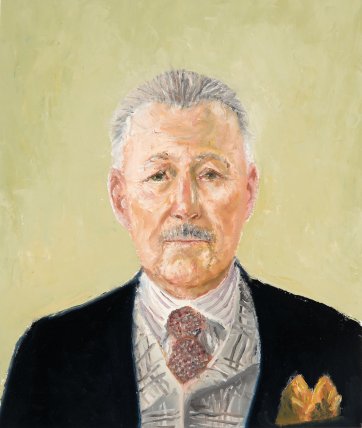

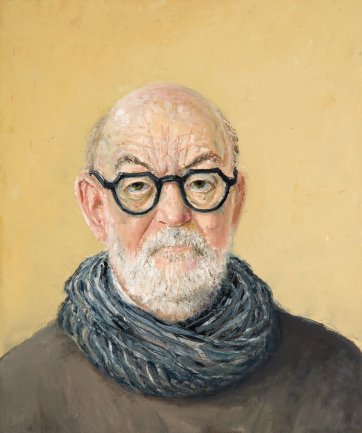

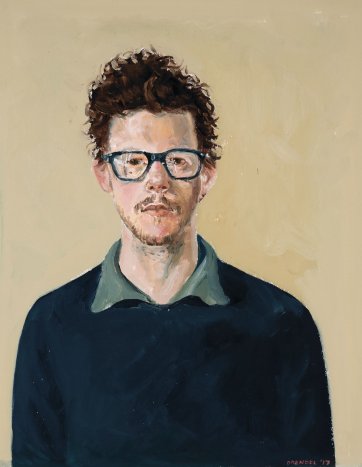

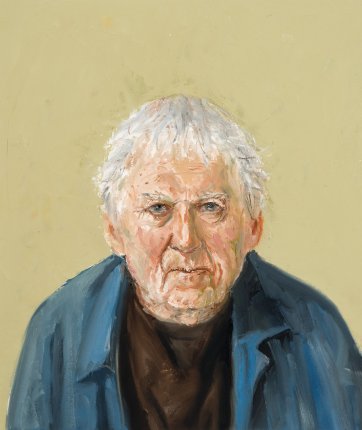

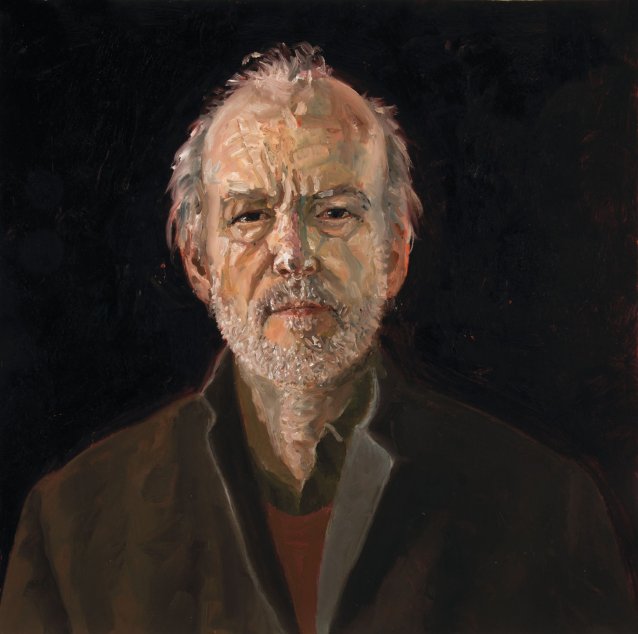

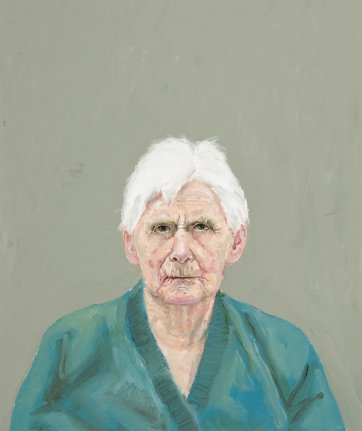

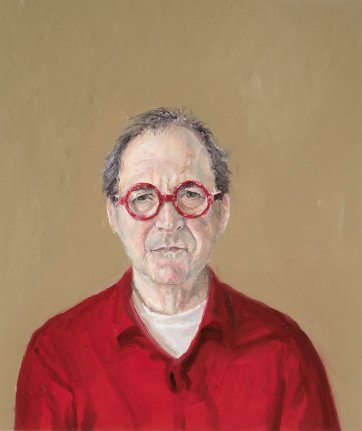

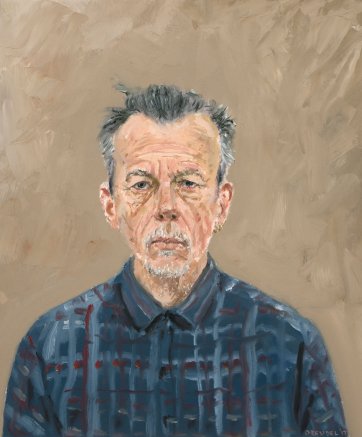

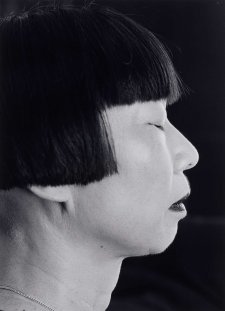

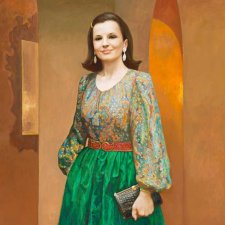

Graeme Drendel is a seriously skilful portraitist, but it’s only quite recently that he’s taken to oil portraits with fervour.

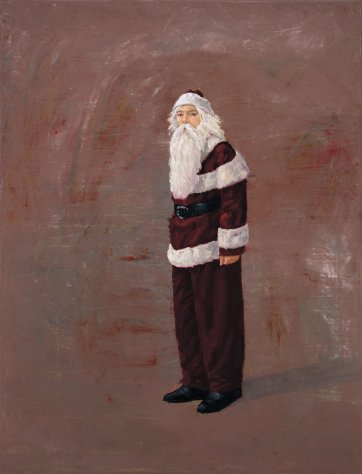

Many professional artists make portraits as a sideline to their principal body of work – landscapes, still lifes, sometimes even abstracts. For Drendel, too, portraiture contrasts with his usual practice; yet his works almost always include human figures. Preparing a big painting for exhibition (he shows with Australian Galleries in Melbourne and Sydney and Beaver Galleries in Canberra) he typically starts with one whole figure. In time, others wander in, take up occupancy. One day even Santa, wary and jaded, sidled from the shadows of his imagination.

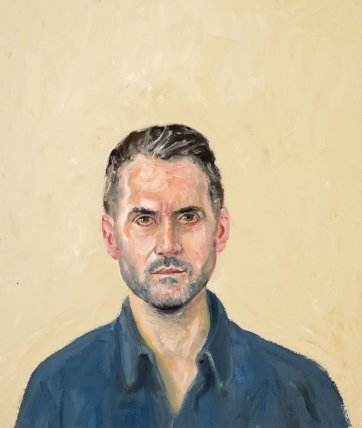

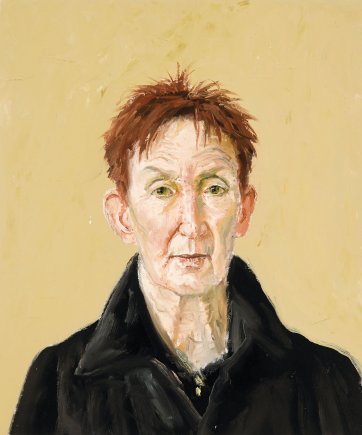

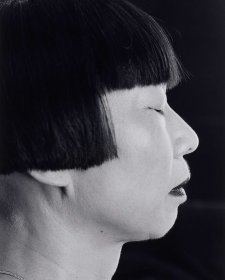

The artist acknowledges that many of the ‘people’ in his paintings are informed by the face and figure of his partner, muse and model, Wendy Horsburgh. Many resemble him, too. Their homogeneity is thoroughly deliberate, and what’s more, while some look almost alarmingly sincere, some a little sleazy, the smooth, regular faces of most are impassive, their expressions equivocal, their ages indeterminate or irrelevant. Those that drop into his paintings are distinctively ‘Drendel people’. But it’s Drendel’s people – those who drop into his house – whom we see in his candid, unaffected portraits.