The Fiona Foley HHH 2004 performance in ultrachrome print on paper takes the fight on in a different way. Multi-coloured costumes, complete with black hoods, were created, modelled, and photographed to call out and speak back to white robes and hoods, universally symbolic of the American white supremacist group the Ku Klux Klan (KKK).

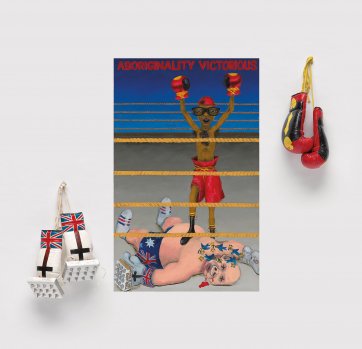

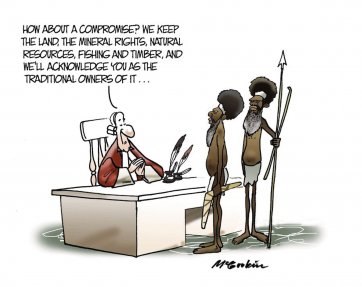

I work in universities, and now posters too have become mainstream – our university’s CV template even has a spot for inclusion of research posters as CV-worthy! Posters though, have grown out of activist movements as primary political communication collateral – and the posters in this exhibition took people back through our post-invasion ages. Nostalgic, poignant, and still everyday ever-present as our collective demands are still to be met. Blak cartoons and Blak-friendly cartoons are always appreciated for their pithy piss-takes in a form that has historically and contemporaneously been mobilised against Blak interests. Cartoons can attain the lowest common denominator all too easily, but they can also raise the heat and level of debate to new clarity.

To my mind though, Oodgeroo Noonuccal’s poems, Son of mine (for Dennis) and White Australia, take pride of place in the ‘hearts and minds’ activism stakes. The burning for justice, the pride in our peoples, the call for collective journey, the embodying of hope for change – it’s all here.

Son of Mine (To Denis)

My son, your troubled eyes search mine,

Puzzled and hurt by colour line.

Your black skin soft as velvet shine;

What can I tell you, son of mine?

I could tell you of heartbreak,

hatred blind,

I could tell of crimes that shame mankind,

Of brutal wrong and deeds malign,

Of rape and murder, son of mine;

But I’ll tell instead of brave and fine

When lives of black and white entwine,

And men in brotherhood combine –

This would I tell you, son of mine.

Oodgeroo Noonuccal (Kath Walker)

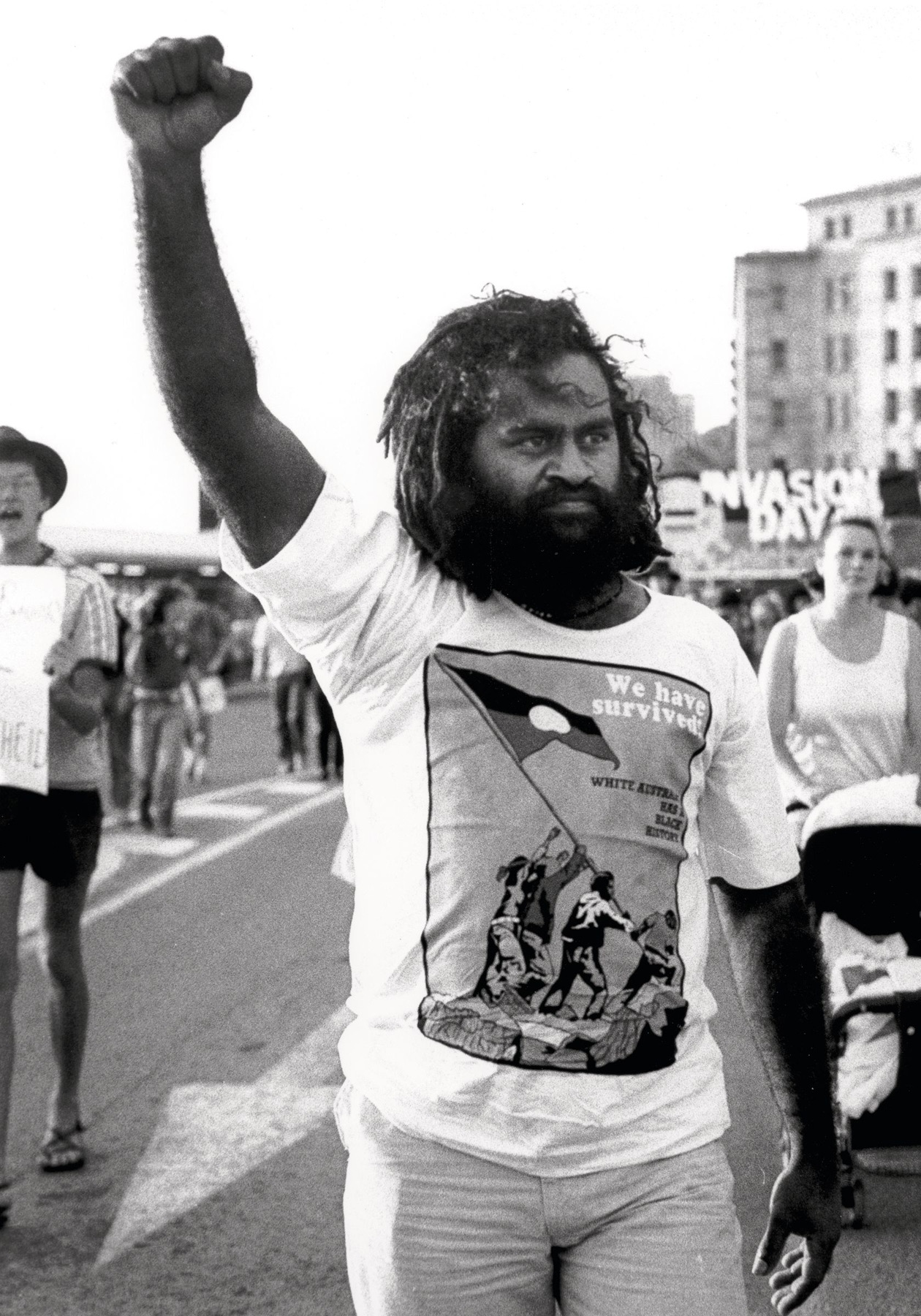

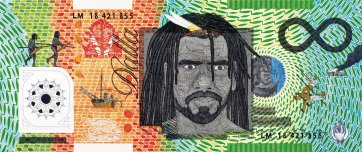

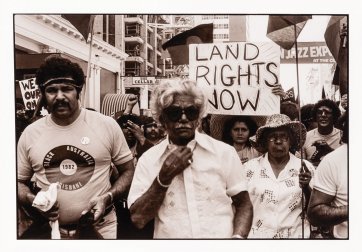

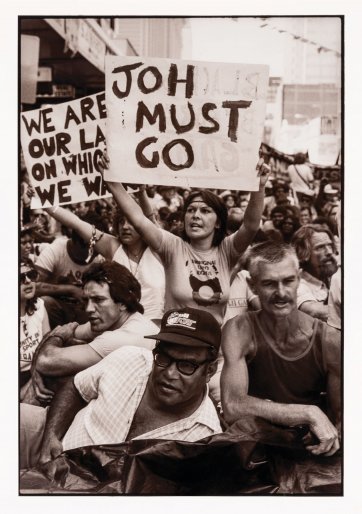

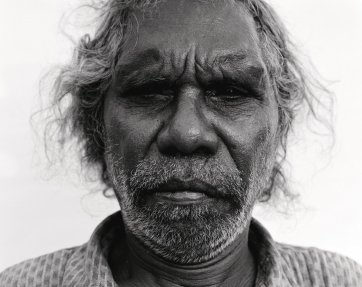

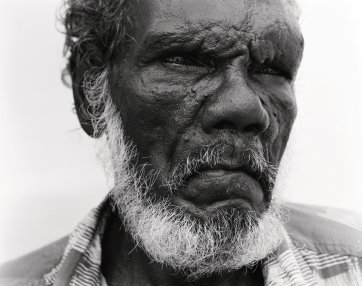

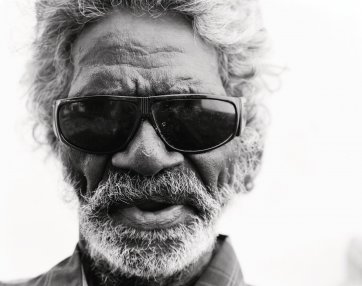

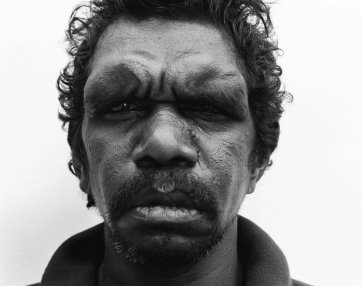

A walk through Queen’s Land Blak Portraiture might well have persuaded everyone that, indeed, activism is an everyday affair for Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders – the program is not a singular one, but one exercised in many different ways, from the ground up, and the calls for political and social change can land on their listeners, readers, viewers in a multitude of ways. Ways that inevitably provoke a response. There’s demand in activism and there is always hope, because to make art for change is demonstration itself that artists believe change is both desirable and possible.

This is an edited version of an essay that first appeared in the catalogue accompanying Queen’s Land Blak Portraiture at Cairns Art Gallery in 2019. The catalogue is available for purchase online.