We don’t know much about this Benjamin Law. Records show he was a white man who arrived in Hobart in 1834. As well as being a sculptor, he was also lithographer, a teacher, a storeman and later a postman. He was obviously also a remarkably talented artist, who produced exquisite busts of First Nations Tasmanians Wurati and Trukanini.

Some history: Wurati was a Nuennone man from Bruny Island – a skilled hunter, boat builder and renowned storyteller who spoke five languages. When conflict escalated between white colonists and Aboriginal people, Wurati was appointed ‘Conciliator of Aborigines’ – which sounds like a peaceful role. In reality, it meant he was responsible for effectively removing Tasmania’s Indigenous people to Flinders Island in Bass Strait. It was ostensibly to protect them, but ultimately meant Aboriginal people were persuaded – by one of their own – into exile and ruin.

Wurati’s wife Trukanini is arguably Australia’s most celebrated Indigenous leader of the 1800s. Her face has also long been used as a symbol of the near-extinction of Palawa people; a reminder of the clear-cut case of genocide on this continent, and the holocaust courtesy of the British Empire. At the same time, it would be incorrect to think of Trukanini as ‘the last of the Tasmanian Aboriginal race’, as she’s long been regarded.

Trukanini’s life was defined by settler violence. British sailors stabbed her mother to death; sealers abducted and sold her sisters; convicts abducted her stepmother; timber-cutters killed her fiancé in a violent and horrific way that reportedly involved cutting off his hands. Even in death, Trukanini was violated. As she had feared in her life, her skeleton was stolen from her grave and was – for years – displayed at the Tasmanian Museum. It is such a dark history, as so much of this country’s history is.

Portraits are attempts to create something permanent out of the fleeting and the temporary. That project can feel virtuous on one hand, but sobering when you consider Australia’s colonial and murderous history when it comes to Aboriginal people. When I see these busts of Wurati and Trukanini, I start asking myself questions. To what extent were these sculptures an attempt to not only preserve the memory of Wurati and Trukanini, but of their people, who were being wiped out methodically? What do they tell us about the time and place in which they were created? Has anything changed? What is being preserved and why?

I also wonder about the exchange that’s taking place. After all, every portrait is fundamentally an exchange, between the artist and sitter. (I give my time and body; you give your time and skill.) Given how Aboriginal people were depicted by white colonial artists as objects – of curiosity, of difference, of scientific study – one core thing being exchanged here is power. It’s something arguably exchanged in every portrait we see. But who wields it? Who is reclaiming it? And who stands to lose it?

Recently, British artist Jonathan Yeo unveiled his vivid blood-red portrait – huge, roughly eight-feet tall – of King Charles. Yeo has also painted Tony Blair, Sir David Attenborough and Malala Yousafzai, but this portrait caught the public attention like nothing else he had done. Upon unveiling, Queen Camilla is said to have looked at the painting and told the artist: ‘Yes, you’ve got him.’ But what exactly, had he ‘got’?

After all, upon the unveiling reactions were varied. New York magazine critic Jerry Saltz called the painting ‘a very reddish radish of a picture’ – a mild and almost affectionate reaction compared to some of the general public. One Londoner took one look and told the BBC, ‘It kind of looks like a massacre’. Another remarked, ‘It looks like a poster for a horror film.’ On artist Jonathan Yeo’s Instagram post of the portrait, the most liked comment simply reads: ‘I’m sorry but it looks like he’s in hell.’

But the reactions to the portrait that really stood out for me were from Black friends – those with roots in the broader African diaspora, and/or Black as in Aboriginal Blak. They found the whole thing hilarious and … well, appropriate. Even when portraits are commissioned by the powerful, they can be sites of disruption, where power is actively questioned and potentially undermined.

Earlier this year, Australian artist, national treasure and the first Indigenous winner of the Archibald Prize, Vincent Namatjira, had a painting of Australia’s richest human being Gina Rinehart displayed in the National Gallery of Australia as part of a retrospective, Vincent Namatjira: Australia in Colour. The painting was one in a series that also included Jimi Hendrix, Scott Morrison, Eddie Mabo and Julia Gillard – all arguably unflattering – but it was noted Mrs Rinehart’s portrait especially bore the same startled expression of someone who just saw an unflattering portrait of themselves.

Mrs Rinehart asked the National Gallery of Australia to remove the picture from the exhibition. The National Gallery bluntly refused. They stated, ‘Since 1973, when the National Gallery acquired Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles (1952), there has been a dynamic discussion on the artistic merits of works in the national collection [and] on display at the Gallery. We present works of art to the Australian public to inspire people to explore, experience and learn about art.’

The subsequent news stories shot across the globe. Mrs Rinehart’s intention of ensuring as few people see the portrait as possible had the opposite effect. Not only did the original portrait now enjoy newfound attention, Namatjira’s other portraits of Mrs Rinehart – which would’ve otherwise not been seen – also resurfaced in the media. They were arguably even less flattering.

And now we had this decade’s most eye-wateringly delicious case study of the Streisand Effect – where efforts and attempts to hide, remove or censor information, instead increases public awareness of the information. It was named after Barbra Streisand, whose attorney’s attempt to suppress the publication of a photograph showing her clifftop residence in Malibu inadvertently drew far greater attention to the previously obscure photograph. Now people are calling for the Streisand Effect to be renamed the Rinehart Effect.

Recently I interviewed Vincent Namatjira. He was pretty casual about the entire thing. He told me, ‘To be honest … with that picture of Gina, that was just my way of seeing Australia’s richest person. That’s the way I just see it, straight from the heart.’ Of her slightly allergic reaction to his work, Namatjira said, ‘That’s her opinion, that’s her business. But wow, that portrait did affect her. It did touch her.’ I should point out that Vincent Namatjira was smiling as he said all of this.

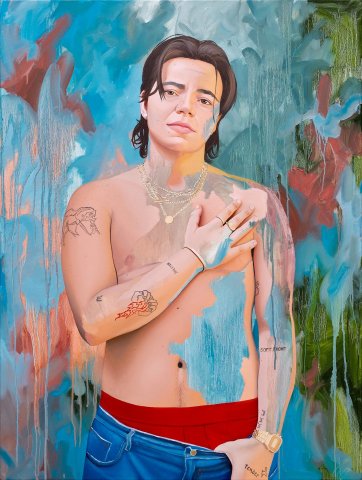

Portraits are sites of contested power. They can brutally assert power by claiming the official narrative, or can unintentionally provoke mirth and, in the process, chip away at power. They can also be an act of reclaiming power. Which brings me to my arse. I’m not bringing up Jordan Richardson’s portrait of me – which featured my bare buttocks – to be gratuitous. But if we’re talking about power, this portrait – and me sitting for it – was, in its own way, a reclamation of power.

On surface level, Jordan Richardson entering his nude painting of me in the Archibald Prize felt like a good prank. Could we get my arse displayed in Australia’s most beloved art competition? Could we forcibly thrust my pert Asian-Australian butt cheeks into the eyeballs of the country’s crustiest white-male art critics? Could we pull it off? To our delight – and my family’s exasperation – it turns out the answer was ‘yes’. But look closer (not too close, you might go blind) and you’ll see other dimensions to the painting, too.

Two years after we met at the 2019 Archibald Prize (for which Keith Burt had painted me and Jordan had painted Annabel Crabb), Jordan shot me a line: he wanted to paint me now. And he wanted to push himself further and paint something more technically ambitious than his previous Archibald-displayed portraits of John Bell, David Wenham and Crabb. He told me: ‘I’m always happy to upset the conservative audience, too, if that’s on the cards.’ Obviously, I was sold.

Then Jordan followed it up with a gamble. ‘Total shot in the dark,’ he said, ‘but how’d you feel about being painted in the pose of a reclining Venus? Not sure if it’s something you can get behind, pun intended, but let me know.’ Jordan attached a reference of a famous nude with her buttocks on display, allowing me to process what I was seeing, and waited for my reply.

What Jordan sent me has some history. Diego Velázquez’s mid-1600s portrait, now known as the Rokeby Venus, depicts Venus nude, reclining on a draped couch, studying her reflection in a mirror held by Cupid. His study of what he considered ideal feminine beauty was controversial at the time, and remained so for centuries. In 1914, suffragette Mary Richardson dramatically slashed the painting with a smuggled meat cleaver, partly as a protest against the arrest of Emmeline Pankhurst, but also over ‘the way [male] visitors gaped at it all day long’.

Straight away, I clocked Jordan’s intent. By referencing the same painting, but putting a gay Asian dude in the same pose, Jordan would immediately subvert assumptions about race, sex and notions of artistic merit. It’d flip the idea of subject and object, turn the tables on the male gaze, and interrogate the centrality of whiteness in ‘Important Art’. It’d be a commentary on the perceived sexual desirability – or lack thereof – of Asian men. It would question power. It would also be really funny.

![Woureddy [Wurati], an Aboriginal Chief of Van Diemen's Land Woureddy [Wurati], an Aboriginal Chief of Van Diemen's Land](/files/1/8/b/4/i10111-th.jpg)

![Trucaninny [Trukanini], wife of Woureddy [Wurati] Trucaninny [Trukanini], wife of Woureddy [Wurati]](/files/c/b/d/0/i10110-th.jpg)