Joan’s My own piece of paradise prophetically taps into the absurdity of this experience. Have you ever found yourself jealous, bargaining with the cards you were dealt and comparing your life to someone else’s? My own piece of paradise forces us to confront our belief that Country, and what we put on it or in it, can be truly owned. We live on Country until we die, and then our bodies and all our earthly belongings eventually become part of the Earth too. Why do we pretend that isn’t the end game? Everyone and everything becomes part of Country. It owns you. Property ownership is an uncanny and absurd thing, yet it is collectively strived for as part of the Australian dream. Even as that dream has slipped through the fingers of generations of people. And still, there are plenty of TV shows about selling multimillion-dollar homes around the world. We watch them in our rentals. Amid the cost of living crisis. How ludicrous.

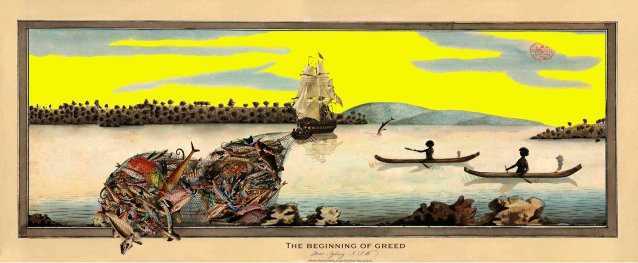

I would see Joan more and more as the years went on, and I realised it didn’t make me feel gross as an Indigenous person to see Indigenous people in her work. I thought it was interesting. In View of New Holland 1770 it was the uncanny that drew me in. I had seen the depictions of First Nations people that Joan digitally collaged into this work before, just not so many in one picture. ‘I claim the entire eastcoast of Australia for Great Britain’ is written on the horizon line, with a tall ship in the distance. There are three different Joseph Lycett landscapes in this one work; the First Nations people were sourced from still more. It is so seamlessly stitched together as a fake composition that it looks real. Irony comes to play. Lycett and many other colonial painters made up the landscapes they painted. Joan’s work is a lie made from lies – but it’s closer to a truth that many First Nations people would recognise as real. There were way more First Nations people around when Lycett was working, they were just deleted from the scene. As a composite of lies, Joan’s work is a pastiche of what the colonists did. The biggest lie was the claiming of the coast. A cut and paste of the idea of Britain onto this continent.

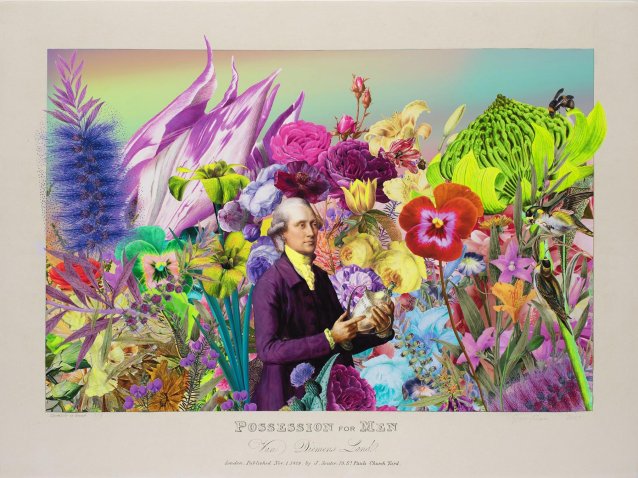

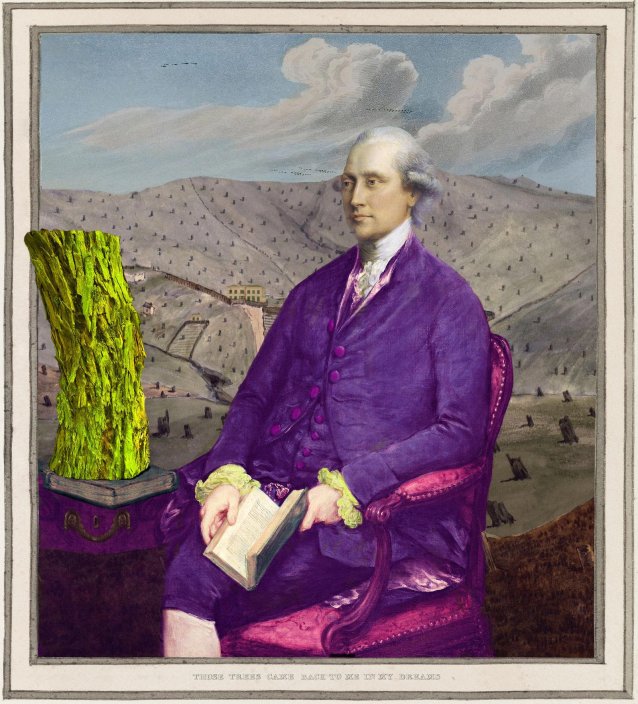

The use of fluorescence as a metaphor for colonisation is easily readable across Joan’s practice; some think of it as her signature. I think the uncanny is her true signature. It needs to feel familiar and weird at the same time for it to feel like a Joan Ross work. Collaging together landscapes housed in collections and reproducing portraits of Flinders, Banks, Cook, Solander, Mrs Macquarie and other faces of people we have never met but think we know. Her titles are like a blunt punchline; found quotes from early diaries and accounts, or made-up ones that sound like they could be. As if Joan is letting you read her work and if you still don’t get it, she’s left a hint in the title for you.

I have spoken to Indigenous friends and family about how non-First Nations people add to the narrative about us. Whether well-intentioned or not, when non-First Nations people tell our stories, it can start to reek of paternalism, or worse.

Cultural appropriation can creep into the picture. Generally speaking, First Nations people are done with non-First Nations people telling our stories, putting words into our mouths, showing us what we look like to them. We have been the greatest subject of European scrutiny for over 200 years.

So how can Joan, a European woman, include First Nations peoples and articulate how she feels about what has been imposed on us in her works, without creating another European narrative and perpetuating the ones that already exist? Joan repurposes historical images so as to avoid imagining-up new depictions of First Nations people which could further objectify or diminish blak bodies. She uses images where Aboriginal people were not the main subjects, or were depicted doing things that were not obviously determined by the viewer, coloniser or artist. She uses images where it isn’t completely obvious that the subject didn’t want to be a subject, or was being used to push an agenda. Hunting, eating around the fire, playing, swimming, fishing. Little dwellings, people climbing trees, everyday activities. By using such imagery Joan is re-evidencing what was there in the accounts all along. This is also part of methods First Nations researchers use to revive old practices. We research old accounts, images and texts. Language revival is probably the most obvious example of this, helped through non-First Nations peoples’ thorough recording of our culture. Some of the most detailed accounts are contained in the diaries of 18th- and early- 19th-century explorers, colonists, surveyors and artists. Just as First Nations researchers rely on that material, Joan does a similar thing. Seeking to neither ignore nor intentionally further objectify.

In The beginning of greed, Joan lays bare the devastation of colonisation for First Nations people and Country. It is a heartbreaking image of two women out in their nawi (bark canoe) fishing, fire on their nawi ready to cook fish and take them back to feed their families. But there is a big ship in the distance pulling a net full of fish that fall out of the frame toward the title, THE BEGINNING OF GREED. People who know the story of Barangaroo the fisherwoman and other Cammeraygal women who belong to Sydney Harbour and its surrounding waters understand this image deeper than the bulging net. Barangaroo is a celebrated woman, and much pride is held in her story; the centring of these women in Joan’s work is subtle and in line with how First Nations people remember her.