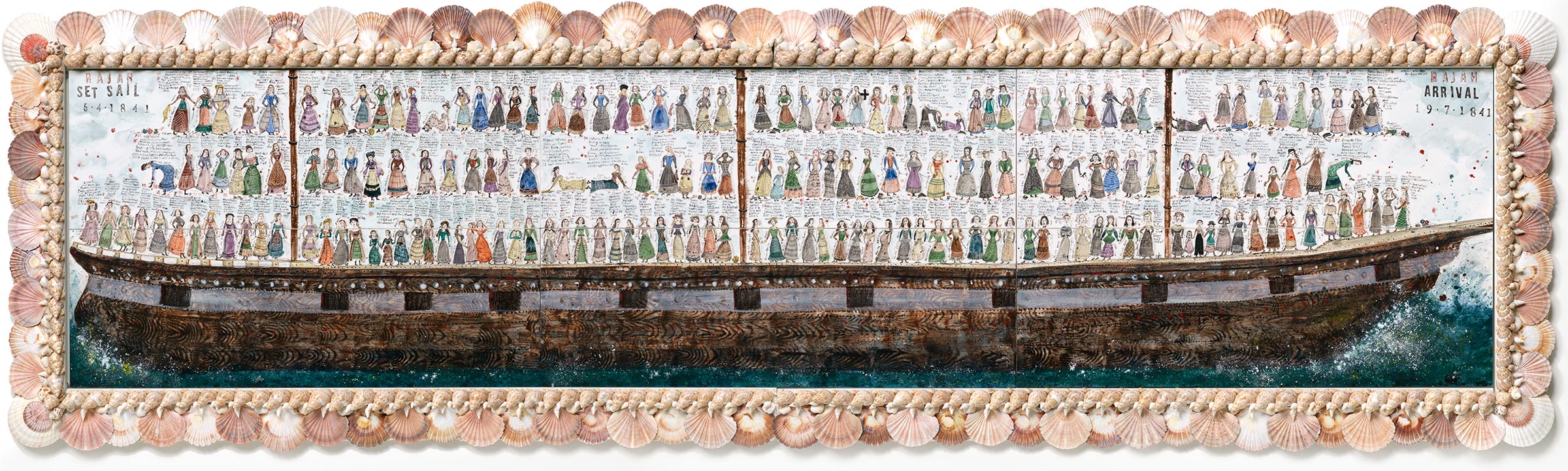

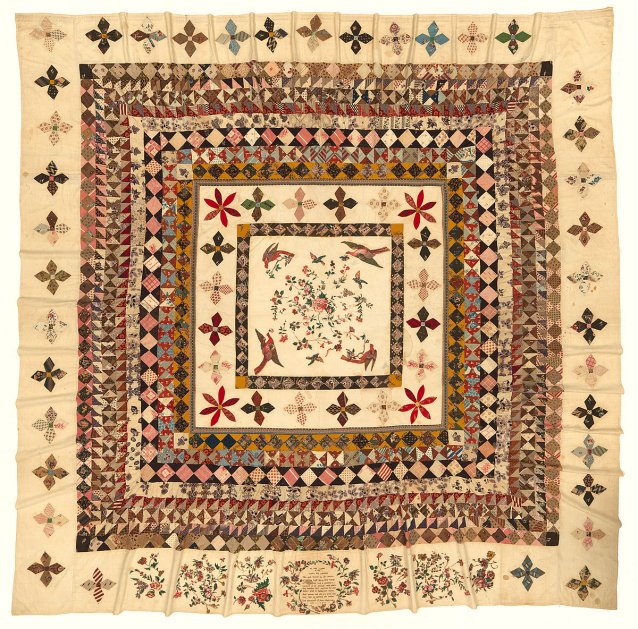

The Rajah was your garden-variety convict ship in most respects. A 352-ton barque constructed in Whitby, it left England in early April 1841 and sailed into the Derwent River 105 days later, having lost only one member of its human cargo. According to the notes made by its surgeon-superintendent Dr James Donovan, over 80 percent of the convicts on board had behaved in an acceptably quiet and obedient fashion, and some of them he even declared to have been ‘very good’. Along with official notification that the colony’s attorney-general and solicitor-general had both been sacked, the Rajah brought with it from London news of Queen Victoria’s pregnancy (Her Majesty’s ‘fair proportion was a matter of much public rejoicing’, apparently), as well as ‘nine varieties of the camellia, four of the magnolia, three azaleas, arbutus, myrtles, &c., &c.’, all imported for propagation by members of the Launceston Horticultural Society by a Mr Davies – specifically, the Reverend Robert Rowland Davies of Longford, who was also returning to Van Diemen’s Land with a £1000 loan from the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. Most significantly, among the numerous items disgorged from the Rajah’s hold was a patchwork quilt – or, technically speaking, an unlined patchwork coverlet – that had been stitched by some of the 180 transportees on board under the supervision of the ship’s matron, Kezia Hayter. It was in this that the Rajah deviated from the norm. Whereas, since the early 1820s, it had been usual to attempt to instill ‘order, sobriety and industry’ in female convicts by supplying them with sewing materials on embarkation, it is unusual for the results to have survived. Quilts and other items could be sold en route, for instance, or put to use on arrival in the colony, stacking the odds against longevity of useful life and preservation. The coverlet pieced together by the Rajah’s women, in contrast, was constructed with posterity in mind, an enduring proof of beliefs about the redemptive power of work, and of the grace and dignity that might be fashioned from graceless, undignified circumstances. It follows that the ‘Rajah quilt’, as it’s now known, has become something of a talisman. Art historians and decorative arts boffins are in thrall to its design, components and construction; social historians salivate over its eloquence as an artefact; and the numerous descendants of the women involved in its creation revere the quilt as a tangible, palpable link to their ‘tainted’ convict forbears.

- About us

- Support the Gallery

- Venue hire

- Publications

- Research library

- Organisation chart

- Employment

- Contact us

- Make a booking

- Onsite programs

- Online programs

- School visit information

- Learning resources

- Little Darlings

- Professional learning

![In prison and ye came unto me [Portrait of Elizabeth Fry, Newgate Prison], 1820 by Richard Dighton In prison and ye came unto me [Portrait of Elizabeth Fry, Newgate Prison], 1820 by Richard Dighton](/files/5/a/e/0/i11547-th.jpg)