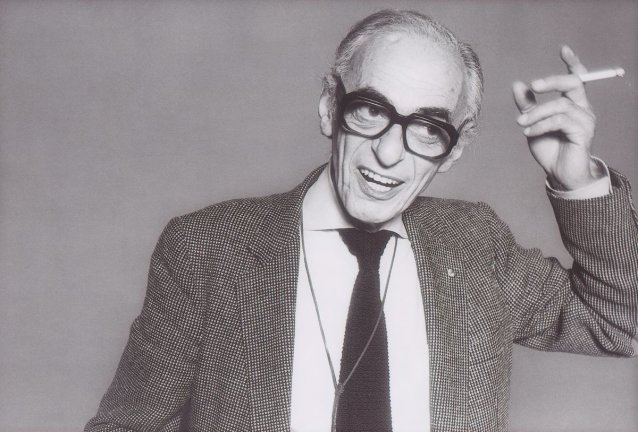

While the bourgeoisie were ‘doing the Block’ – seeing and being seen in Melbourne’s famous arcades – towards the upper, Paris end of Collins Street, there was another apparition that warranted attention. It was the year 1939 when a young Louis ‘Athol’ Shmith, (1914-1990), opened his photographic studio in the Rue de la Paix building, number 125 on the southern side of Collins Street. The building, originally intended for cosmetics entrepreneur Helena Rubinstein, was in close proximity to other prominent photographers of the day, Arthur Dickinson, Jack Cato and Spencer Shier. And a plush setting it was, with its blue furniture and carpet a shade of deep pink, the luxury setting perhaps an alluring one for fashion doyenne Lillian Wightman of Le Louvre, just across the way. Projecting style and charisma in his tailored suit with Windsor knot, Shmith’s presence on upper Collins was befitting of the faux-Parisian élan. Indeed, Shmith’s arrival in the heart of the exclusive area was timely, for the blossoming of the ‘New Woman’ with her ‘New Look’ was beginning to materialise.

At the time he relocated his studio from St Kilda to Collins Street (at a mere twenty-five years of age), the precocious Shmith had already achieved excellence, both in Australia and abroad. Elected fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, London, in 1935, and fellow of the Royal Photographic Society in 1939, he was a regular entrant and judge in the Salon exhibitions of the period. Shmith’s fashion illustrations and wedding photography for Melbourne’s elite had also earned him plaudits and contributed to his burgeoning reputation.

It was only weeks after opening his doors, however, that the outbreak of the Second World War brought a halt to Shmith’s studio operations. His attempt at enlistment thwarted due to failing his medical examinations, he assisted the army with vital photographic analyses, including decoding details related to the American landing in Italy. Shmith also joined the growing number of photographers contributing to the nation’s historical documentation of the war – as a photographer on the home front, he took portrait photographs of hundreds of servicewomen and men. In an interview in 1989 with Isobel Crombie, then Curator of Photography at the National Gallery of Victoria, he said, ‘Every soldier going to war was having his picture taken, and when the Americans came here they swamped the studio’.

In contrast, there was a notable absence of portraits of servicewomen throughout the First World War period. Serving in traditionally female occupations, Australian women filled positions as nurses and in other medical roles for the Australian Army Nursing Service, and as volunteer fundraisers and teachers for the Red Cross. Most married women were expected to stay at home in a caretaker role.

Following the Great War, several feminist associations emerged in Australia. In 1929 the emergence of the United Associations of Women, one of the more radical feminist groups of the early-mid 20th century, assisted greatly in challenging society’s staunchly conservative views. Led by President, Jessie Street, (1889-1970), and her committed group of feminists, the women campaigned vigorously to achieve gender equality, with one aim being to secure economic independence for married women.

Operating under the motto ‘For freedom and equality of status and opportunity’, the women continued their cause throughout the 1930s and into the 1940s, playing a key role in organising The Australian Women’s Charter Conference in 1943, a gathering which focused on the question of how women’s interests would be advanced in the post-war reconstruction period. The conference resulted in the landmark feminist manifesto, The Australian Women’s Charter. Written by women, the document outlined reforms for women in the post-war world, including securing real equality of status, opportunity and liberties for both men and women. Subsequently, women were presented with new opportunities across various fields throughout the Second World War period. In the case of photography there were unprecedented developments, with women (for the first time) appointed alongside their male counterparts in a range of capacities, from darkroom assistants and technicians though to professional photographers. The increased number of both male and female photographers covering the home front resulted in the emergence of many new photographic styles, with an accompanying range of meanings and associations.

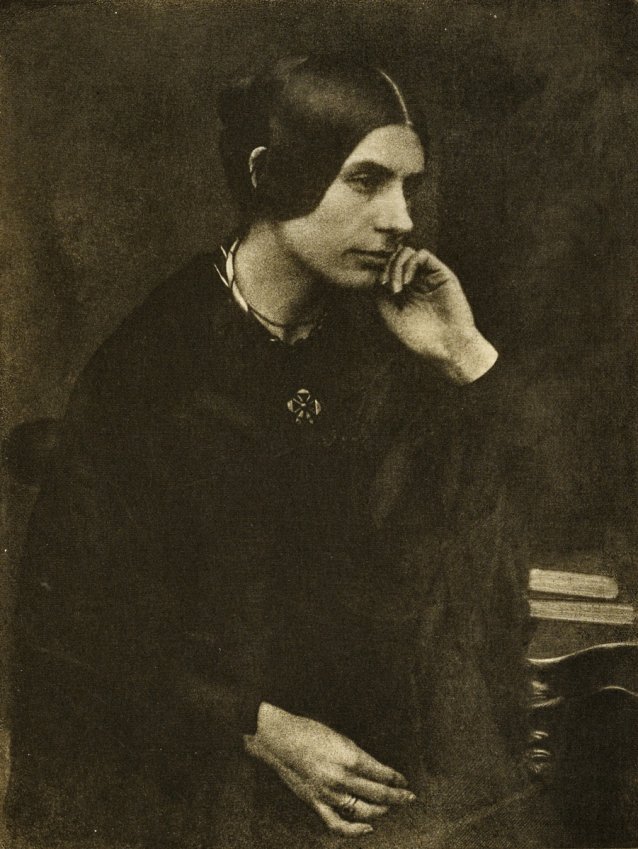

A memento of a loved one, for instance, was vastly different from a portrait commissioned by the Government to entice capable young debutantes from well-to-do backgrounds to enlist. Shmith’s portrait of Sergeant Marjorie Alice Weynton, (1922-2015) provides an interesting example. Weynton was the wife of Lieutenant Alexander Gordon Weynton, (1905-1966), a signaller in the 8th Division who was captured and became a prisoner of war in 1942. The personally commissioned portrait of Marjorie was likely a keepsake for her husband to carry with him during his military service. It’s evident in this image that Shmith is attuned not only to the character of each of his sitters but also to the function and meaning of his portraits. By photographing Weynton with her eyes cast towards the distant horizon, the photographer not only suggests her heroic qualities but also conveys a sense of her strength and hope. The fact that Shmith’s portrait reveals a certain truth of character is assisted by the image’s insistent realism; while it may use diffused mid-tones and dappled light, and be Pictorialist in manner, it nevertheless retains a lucid, contemplative quality.