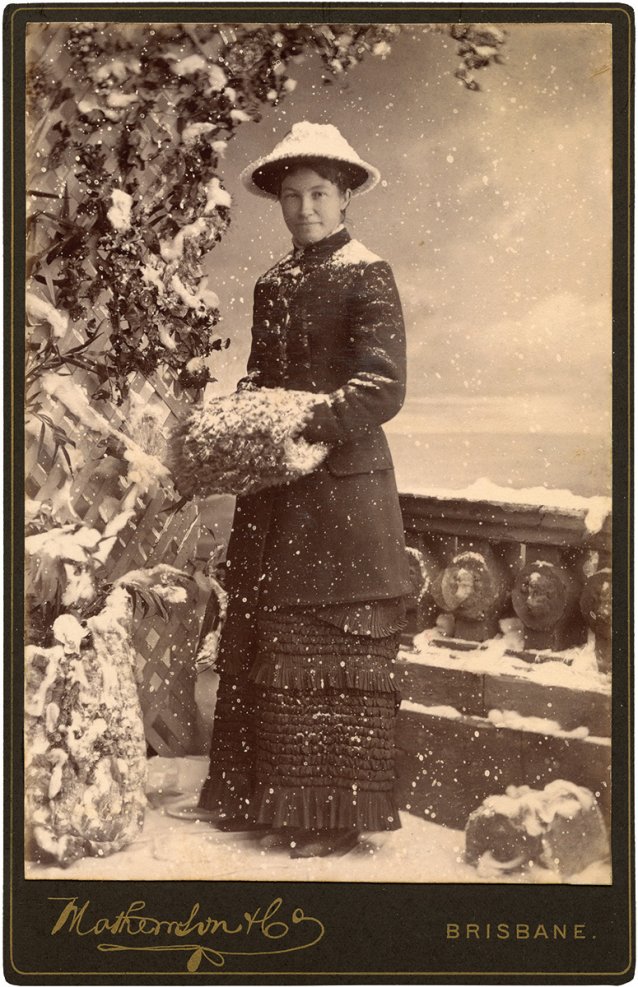

‘This is a palace of photography. Not in its luxury … but in the completeness of the arrangements made for lighting, posing, staying and taking.’ Such was a journalist’s description of Thomas Mathewson’s new studio on Queen Street, Brisbane in 1899.

Today we are taking more photographs than ever before, and sharing almost every detail of our lives across the many platforms of digital media. However, while the advent of smart phones and social media has revolutionised the technology, the inherent nature of portrait photography hasn’t changed. It has always been about capturing the ideal depiction of oneself for longevity and sharing it with others – a controlled means of self-representation.

For our current exhibition, ‘Sit. Pose. Snap. Brisbane Portrait Photography 1850 – 1950’, Museum of Brisbane drew from one of Australia’s largest collections of portrait photographs, amassed by local resident, Marcel Safier, to explore the variety, trends and historical progression of photographic types through the first hundred years of photography in this city. Beyond simple images, photographic portraits are socio-historical objects that reveal the relationship between technology, business and identity. It is this connection we explore in the exhibition.

Photography arrived in Brisbane in 1850 by way of a travelling salesman, and a few short-lived studios were established in the late 1850s, with southern-trained photographers offering daguerreotypes and ambrotypes.

William True Bennett, an American photographer, subsequently introduced a more affordable type of photograph, the tintype. However, it wasn’t until the popularisation of the carte de visite that photography became a viable business in Brisbane.

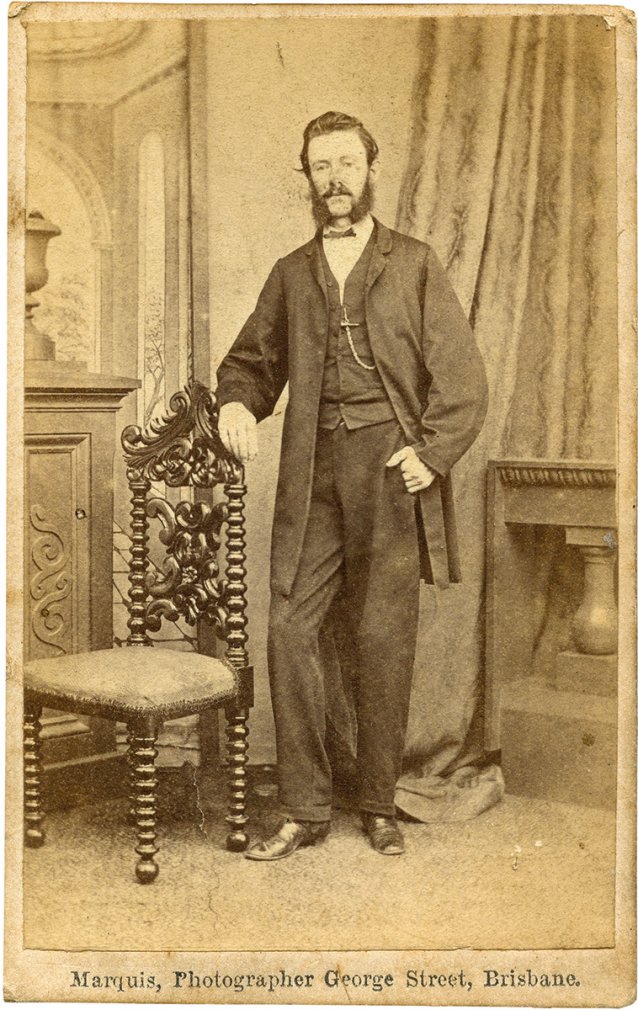

The carte de visite was patented in 1854 by Frenchman Andre-Adolphe-Eugene Disderi. It was an adaptation of the 19th century calling card, used by people to introduce themselves to new acquaintances when calling on friends and relatives, or when conducting business. It was five years before the carte de visite started to gather popularity. This was largely due to the first photographic portraits of members of the Royal Family becoming readily available, starting with those made by Mayall in England and Disderi in France. Not only did the distribution of images of the Royal Family have an impact on the growth of portrait photography, the poses they adopted were then imitated. Daniel Marquis’ photograph of Daniel Hoins on his 21st birthday exemplifies this, depicting the sitter in one of the classic poses of the period.