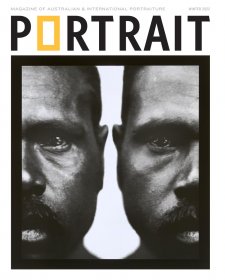

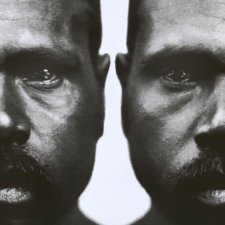

‘My name is Benjamin Warlngundu Ellis. I am a Gudanji/Wambaya man of the northern Barkly Tablelands and inland freshwater Country of the Gulf of Carpentaria. I am a self-taught professional photographer who has been active since around 2012, the body of my work devoted to championing Ngarrinja (Blakfulla) cultures, traditions and spiritual lands across this continent.

Since around June 2021, I have been in conversation on the phone with Penny – initially for an upcoming exhibition. Over the course of time (read: countless hours), through these dialogues I have been able to self-reflect on my profession and share with Penny intimate insights into the multidisciplinary practice of documenting First Nations mob.*

This is (a very small part of) my story.’

*Note: some kin terms differ throughout; the emphasis here is acknowledging the mob to whom one belongs.

Over the last few months, in calls between Benjamin in Burrulula (the traditional name for Borroloola), and me on the lands of the Ngunnawal and Ngambri peoples in Kamberri (the traditional name for Canberra), we have talked (a lot, as Benjamin says) over a shared drive of image files: 170 portraits from the last decade of Benjamin’s practice that he selected from his archive of more than 128,000 images.