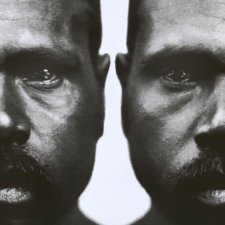

Before David Parker became a highly-acclaimed cinematographer, screenwriter and producer, he was a photographer. He was there with his camera at the genesis of Mushroom Records, at early Cold Chisel gigs, on the set with Molly Meldrum in Countdown’s hey-day, at the airport when the Village People arrived on their Australian tour. AC/DC posed for a portrait in the courtyard of Parker’s Fitzroy studio.

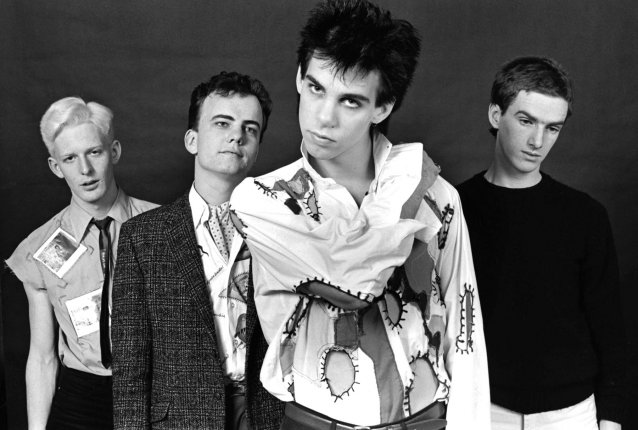

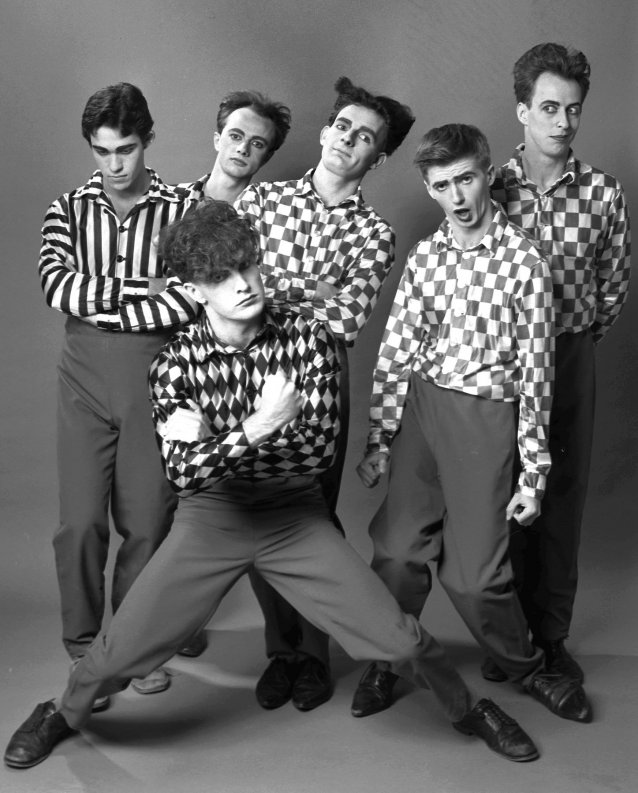

1 AC/DC (Bon Scott, Malcolm Young, Phil Rudd, Angus Young, Mark Evans) at Parker’s studio, Fitzroy, 1975. 2 Cold Chisel (Jimmy Barnes, Ian Moss, Don Walker, Steve Prestwich, Phil Small) at Bombay Rock, Sydney Road, Brunswick, 1979. Both David Parker.

© David Parker

Time for photographers to trawl back through personal archives was one of lockdown’s silver linings. (Parker is not the only photographer I’ve known to have embarked on this long-postponed mission.) He was surprised at how many images he rediscovered going through his files of negatives from beginning to end – ‘my descriptions were wanting to say the least’. His selection went on display in an exhibition A COOL WORLD: Photographs by David Parker of the 70s and 80s music scene in Melbourne at the Brunswick Ballroom.

The portraits in Parker’s exhibition span the decade from 1973, the early days of Australian rock. Ross Wilson was riding high following his number one single, the iconic ‘Eagle Rock’ (with Daddy Cool), and, as Parker puts it, ‘the Skyhooks had been kicking around, not as the Skyhooks’. The future founder of the famous and influential label Mushroom Records, the late Michael Gudinski, ‘was still at school but running dances at the Caulfield Town Hall’. As Parker reflected of the time: ‘There was a real undertow that was starting to drag music out of the garages into the clubs and into the town halls and the emerging talent was quite prolific – amazing talents in performance and composition.’

Parker’s is a Melbourne story, from the perspective of an outsider. He grew up in Moorooka, a suburb of Brisbane, moving south in the 1960s to study photography at RMIT, via a stint in mining at Mount Isa to fund his studies. ‘What I experienced was so dynamic – the arts scene, comedy scene, theatre scene. There was a climate and progressiveness that was allowing all these fields to flourish and I was there recording it. It was the most exciting time.’

In the early 1970s, Parker was working as ‘a stringer’ – a freelance photographer – taking showbiz portraits for the magazine TV Times. Gudinski had started ‘booking acts with all this energy’ and gave Parker the job of photographing his bands. Parker also loved the music – of Skyhooks he muses: ‘That glam-rock look, ridiculous costumes, and those gritty Melbourne songs that had a base to them and were a wonderful observation of the world we lived in – particularly north of the Yarra.’

Renée Geyer brought blues and Nick Cave brought grunge. ‘These performers were all so different, and you had to photograph them differently too.’ Split Enz ‘had a clear idea artistically and would arrive [at my studio] beautifully prepared with all their costumes made and fitted. It all looks chaotic, but it wasn’t. They were very well thought out publicity campaigns.’ Parker also shot album covers such as the black lamb at the Victoria Markets for the Skyhooks’ Straight in a Gay Gay World, which won the Album Design Award at the King of Pop Awards in 1976. The production of cover art for original releases on LP vinyl had ‘a whole creative industry built around them’. As Parker recalled, they were ‘a sophisticated high-design exercise’.

While the focus of A COOL WORLD is his music photography, during these years Parker was capturing show business in general: ‘If TV Times wanted a centrefold – bands or television stars – a publicist would set that up and I would get a small amount of time to set up a studio in a hotel room next to theirs.’ I asked Parker about his approach to portraiture: ‘The recording of a portrait of anyone is recording the relationship you develop,’ he told me. ‘Whether that is in ten seconds or two hours, you are capturing a moment of that relationship. That is what I really concentrate on – the camera is secondary: it is there to record. It’s about the relationship.’

Parker became the stills photographer on Countdown in the late 1970s and early 80s era. Many of the recordings of Australia’s iconic popular music show were not retained – in the moment, often it is not comprehensible that history is being made. Parker’s archive includes some of the only documentation of many performances. One example is his portrait of Olivia Newton-John, summed up in Parker’s exhibition label: ‘Olivia’s career – four-time Grammy Award winner, five number ones in the US, two Platinum and two double Platinum albums and 10 Gold albums. She is one of

the best-selling music artists of all time. Along with most of the Countdowns of this era, the tapes were erased.’

Countdown producers worked out of the ABC studios at Ripponlea, where cast, crew and special guests would hang out before the show. For a photographer, Countdown was a gift: ‘It was well lit! In a concert situation with long lenses and low light it’s touch-and-go managing camera-shake and image-blur with many factors working against you. At Countdown, I was a few metres away from the band and the little crowd were very malleable – they gave you room. The stars knew how important the publicity photographs were and offered the opportunity to shoot them.’

Parker writes that Meldrum ‘was always uneasy about being photographed – you had to ambush him or be surreptitious about it. He made working on Countdown a crazy, roller coaster ride’. One such unpredictable moment saw a very-nervous Meldrum interview Prince Charles in 1977 (the moment was not broadcast). As Parker recounts: ‘Molly led the conversation with “I saw your mum the other night …” to which Charles interjected with “You mean Her Majesty, The Queen”. Molly never recovered, but did put his hand on Charles’ upper thigh and apologised for not being able to complete a sentence.’

Parker shares one portrait that was not taken in Australia: the shot of ABBA live taken in Copenhagen in 1979. During a three-week international tour with Meldrum, Parker took this image while being pursued by a conscientious bouncer: ‘It is a one in a million – close together and all singing. It looks like a set-up, but it is actually mid-concert using a 300mm lens from way down an aisle. One frame only.’ The fun didn’t stop there. ‘Molly and I partied on with ABBA then got in a cab to go to our hotel – a hotel we didn’t remember the name of or where it was. Eleven hotels later, we found it. As dawn broke.’

I was excited to meet Parker and his creative and life partner, film director Nadia Tass while going through some of Parker’s archive for the exhibition Starstruck: Australian Movie Portraits. This meeting, and then staying in touch, has been a particular personal highlight in my time as an National Portrait Gallery curator. Parker’s and Tass’s first feature, Malcolm, is my favourite film. Growing up, my family would watch a videotape of this hilarious urban heist movie, in which the iconic Melbourne tram plays a starring role, so often that quotes from the screenplay became part of our everyday intra-family language. I didn’t think I had much in common with Elton John – but talking with Parker I realise I do. Elton is also a fan of Malcolm, and even keeps a Melbourne tram in his personal collection in the UK. Parker photographed Elton performing in a feather costume at the South Melbourne Football Ground in 1974, and later shot and directed him in Manchester for the AFL’s ‘I’d Like To See That’ campaign.

Relationships and connections are at the core of Parker’s portraiture. His delight at having been there in the thick of it during the rise of Australian rock is palpable in the stories he tells around all of these images. Importantly, this selection from Parker’s archive is an eloquent demonstration of how singular portraits can form a collective portrait of a time and place: his photographic archive not only illustrates moments within the individual biographies but is also an extraordinary time capsule of the place from which Mushroom Records, Countdown, and so many stellar careers grew.