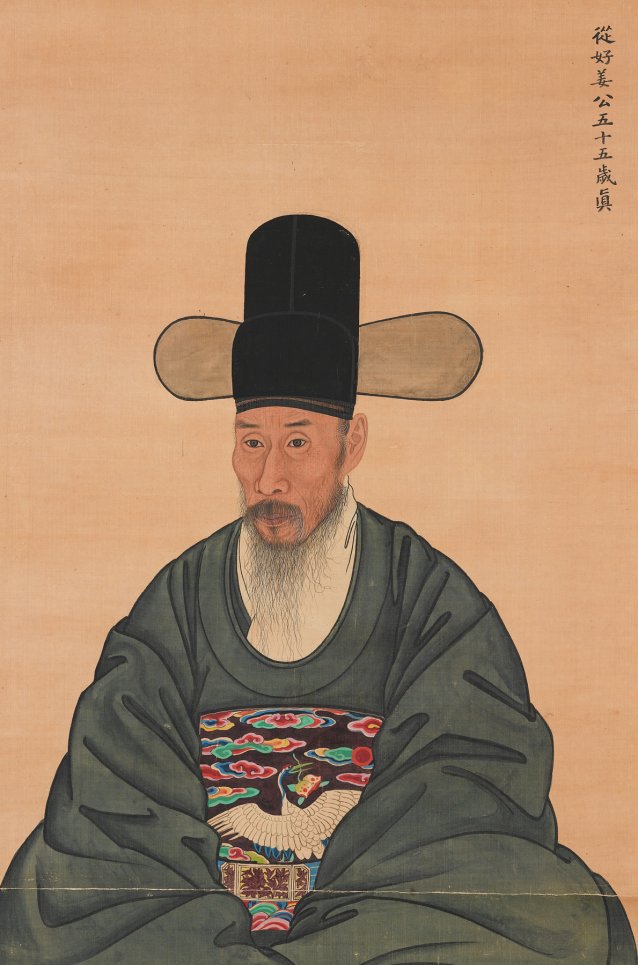

Nine years later, at age 70, Kang Sehwang’s portrait-poem alluded to this dual identity – as nobleman in government service and artist with an elegant and unconventional mind – with the words: ‘Wearing the hat of an official and the robe of a hermit, He holds a government post, but his heart is for solitude in the mountains’.

It was an indication that Kang wished to show the world his self-identity as a reclusive intellectual. In order to express his inner consciousness, he elaborately depicted each strand of his beard and threw himself into realistically portraying his wrinkles, skin, compressed lips, and pupils. The poem written in the blank areas of the painting reveals that the free-spirited Kang Sehwang (at his age) took pride in his wealth of knowledge and artistic talent. He expressed confidence in achieving the ‘Three Perfections’ – the mastery of poetry, calligraphy and painting – which were the highest virtues of the literati during the Joseon Dynasty.

In the overall history of the Joseon Dynasty, the eighteenth century – when Kang Sehwang was artistically active – is considered a local Renaissance, with the blossoming of art and literature. Joseon intellectuals who lived in this dynamic period began to awaken to new knowledge and experiences introduced from the West, and produced distinctive artworks. Kang built his own aesthetic based on this intellectual curiosity, combined with his talent and passion for artistic expression, and developed mastery in elements including landscapes and portraiture, as well as painting the ‘four gracious plants’ – plum, orchid, chrysanthemum and bamboo – a highly significant genre in literati painting.

Moreover, he was held in high regard as a critic and thinker, due to the breadth of his knowledge and discriminating eye for art and literature. His active engagement and artistic acumen allowed him to build a network of contacts from diverse social backgrounds, stretching from the king to the jungin (middle people between aristocrats and common people). Indeed, Kang Sehwang placed himself at the heart of the rapidly changing art world of the eighteenth century.

Besides this self-portrait of Kang Sehwang, revealing his strong sense of identity, the National Museum of Korea holds another portrait of Kang done by Yi Myeonggi (1756- pre-1813), one of the prominent court painters in the late Joseon period. Yi was famous for his realistic and refined paintings, works that employed western shading techniques. Kang Gwan, the third son of Kang Sehwang, stated that this portrait ‘depicted my father’s spirit and mind most satisfactorily’.