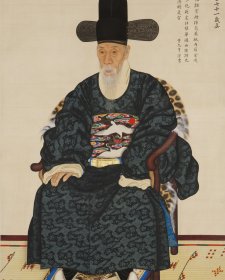

Originating as illustrations for handwritten books and illuminated manuscripts, portrait miniatures came into use among royalty and the nobility during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries for purposes such as the transacting of engagements and marriages, the displaying of political allegiances, and as expressions of one’s amours and attachments. By the second half of the eighteenth century, miniature painting had become something of a profession, with the emerging mercantile and aspirational classes providing a market for these delicate, private tokens of friendship, kinship and affection. Miniaturists began exhibiting their works in the Royal Academy’s annual shows soon after the Academy’s inception in 1768, and artists such as Richard Cosway (1742–1821), painter to the Prince of Wales (later George IV), were not only successful and prolific portraitists but highly fashionable ones too. Cosway, who developed a distinctive style in which the tiny stippled details of faces were contrasted with the expressive brushstrokes by which he delineated upper bodies and cloudy backgrounds, was known for making his sitters look alluring and elegant, or – as in the case of his epically dissipated royal patron – charming and respectable. His sitters included eighteenth-century fashionistas like Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire; national heroes like the Duke of Wellington; and celebrities, including the courtesan Jeanne Bécu, aka Madame du Barry, who became Louis XV’s ‘official’ mistress in the 1760s. During the same period, artists including John Smart (c. 1742–1811) and Ozias Humphry (1742–1810) sought permission from the East India Company to work in Chennai, Mumbai and other outposts, creating portraits for expats and officials to send home.

Miniatures were therefore a well-established form of sentimental currency when Britain, in 1786, decided to expand its empire to encompass much of the continent known as New Holland, the eastern seaboard of which James Cook had charted sixteen years previously, and which had been successfully pitched to the government by Cook’s shipmate, Joseph Banks, as an appropriate site for a colony. It might thus be argued that miniatures with early Australian associations have a particularly potent aura or poignancy, being portraits that encapsulate closeness and intimacy at the same time as they suggest absence, and separation across vast, unfathomable distances. You can’t help but feel, for example, for Lieutenant Ralph Clark, who – apart from his infamous opinion that female convicts were all ‘damned whores’ and ‘ten thousand times worse than the men convicts’ – is primarily remembered for the journal in which he chronicled his tour of duty to New South Wales from 1787 to 1792. The first part of it includes his observations of the journey to Sydney on the Friendship, one of the convict transports among the eleven ships that formed the First Fleet. As abstemious and sanctimonious as he evidently was, the depth of Clark’s sadness at being separated from his wife Betsey Alicia and son is palpable. ‘To Botany Bay I must go’, Clark sighed before the Fleet had even lost sight of England; ‘I trust in God that it is all for the best [for] if I thought otherwise I never should have thought of leaving the best of women and the most sweetest of boys.’ Most days he wrote of missing them, dreaming of them, fearing for their wellbeing and praying to the almighty to protect and/or bless them, and in addition made numerous references to his interactions with a miniature of his wife ‘which we had done by a limner’ prior to his departure. On Sundays, he’d remove the portrait of his ‘Beloved woman the most tenderest of wives’ from the bag in which it was kept and kiss it. ‘Read the Service for the day and the Psalms and kissed my beautiful Alicia’s Picture out of its little bag this morning ten thousand times’, notes the entry for 23 October 1787, for example. On 4 November it was: ‘This being Sunday took my beloved Alicia picture out of its prison and kissed it I believe a thousand times.’