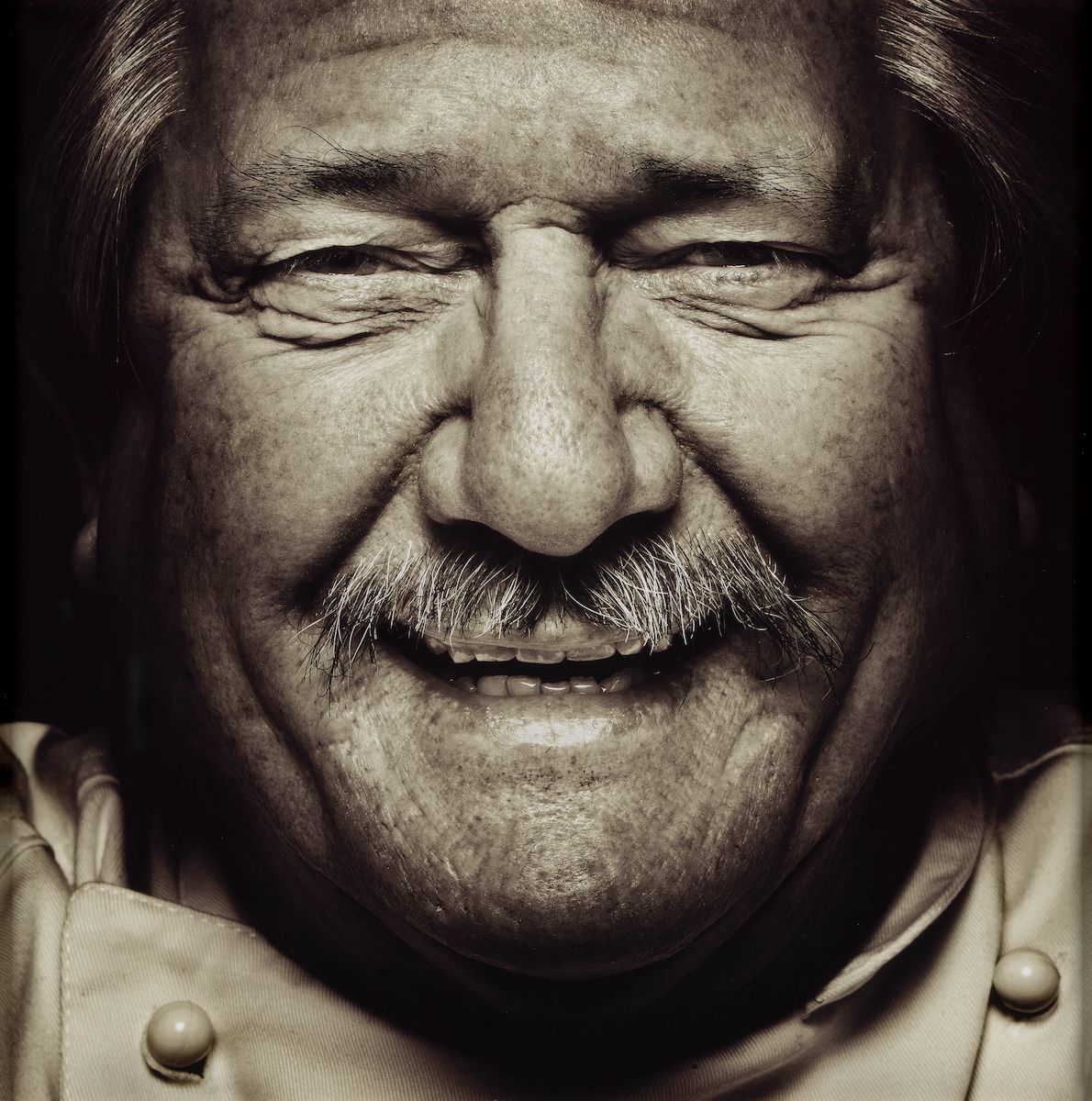

The forerunner and inspiration behind this ‘Nouvelle Cuisine’ was legendary master of modern French gastronomy, Fernand Point, at his three-star Michelin Guide restaurant La Pyramide, in Vienne, France. Although chef Point had died in 1955, the restaurant –under the guidance of his formidable wife, Madame Point – continued. His protégés, the leaders of the new movement, referred to as the ‘Petits Points’, were among the world’s great contemporary French chefs: Paul Bocuse, Alain Chapel, Jean and Pierre Troisgros, Michel Guérard and Roger Vergé. Point’s compilation of over 200 recipes, Ma Gastronomie, was published in 1969 and became one of Bilson’s culinary bibles. Through the introductions of the Chagnys of Château du Châtelard in Lancie, the Bilsons met these luminaries and were wined and dined in their three-starred regional restaurants.

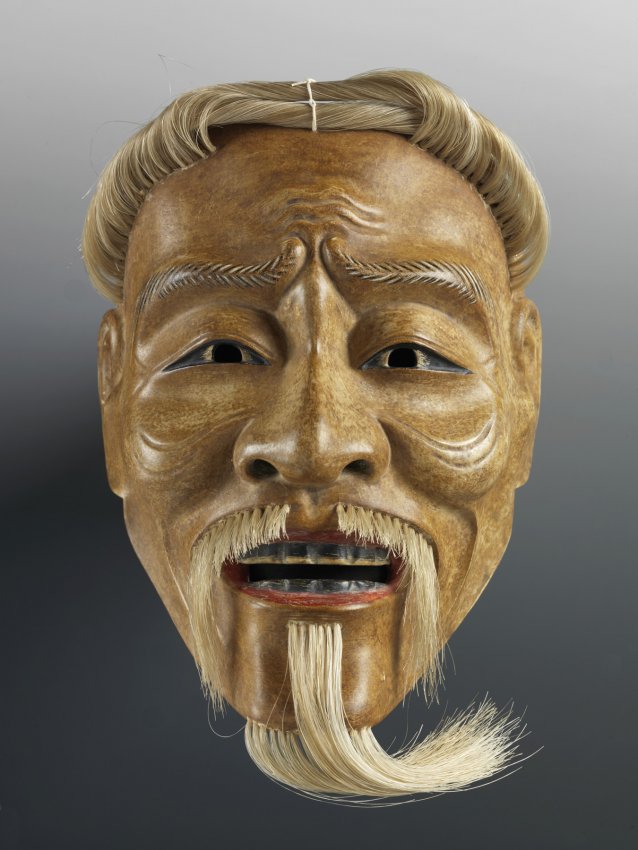

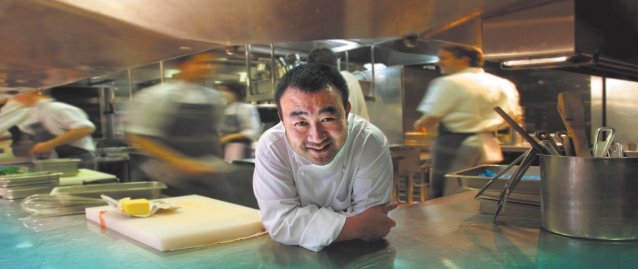

French-Japanese culinary cross-pollination began in the 1950s when Japanese journalist Shizuo Tsuji decided he wanted to learn to become a chef, and went to France to train. He returned to Japan to run the Tsuji Culinary Institute in Osaka, and through his regular visits to France and friendship with Madame Point, encouraged Paul Bocuse ‘an emerging new talent’ to come and study Japanese cuisine. That was in 1965, when Bocuse had just gained his first Michelin star. By 1977, with the international reputation of the Petit Point chefs booming (marking the ascendance of the celebrity chef phenomenon), Bocuse helped Tsuji purchase a French chateau in which to set up a finishing school for Japanese chefs keen to learn the art of French cuisine. As Bilson has noted, with Japanese interest in French wines growing, Japanese chefs adapted French flavours to make their own dishes more compatible with wine, rather than tea and spirits.

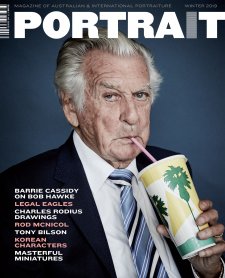

The Bilsons returned from France and redeveloped – with architect Glenn Murcutt’s design – Berowra Waters Inn on the Hawkesbury River. Inspired both by the river locale and what they had seen, eaten and learned while overseas, the prix fixe menus at the restaurant introduced a new level of fine dining. Although over an hour from Sydney and accessible only by boat or seaplane, Berowra Waters drew national and international interest, receiving critical recognition of an emerging modern Australian cuisine: bookings were months in advance.