When artist Arthur Boyd died just shy of his seventy-ninth birthday in 1999, the obituaries recalled a man defined by a gentle disposition. Fondly reminiscing decades later, Barry Humphries wrote: ‘of all the friends I have had in my life, I miss Arthur Boyd the most’. Humphries remembered Arthur as ‘loveable, decorous, slightly apologetic’. Art museum director James Mollison described Arthur as ‘a deeply humanitarian man’.

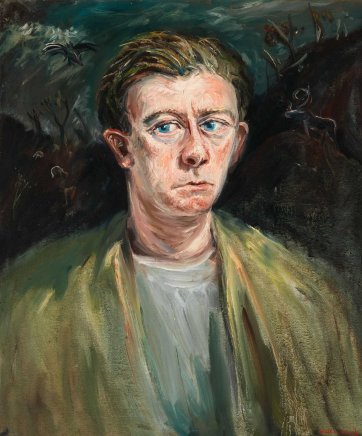

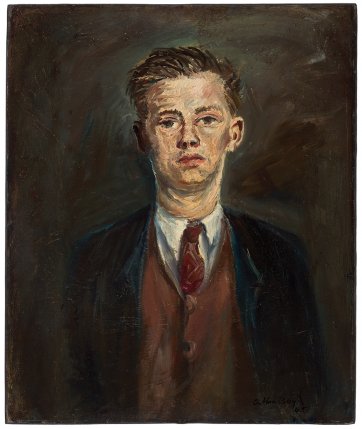

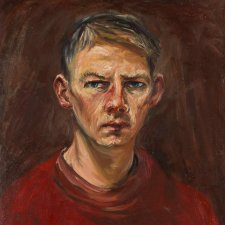

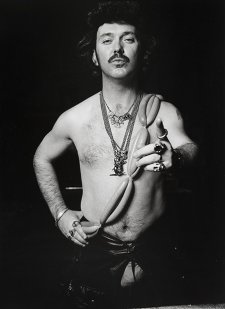

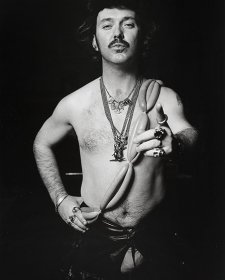

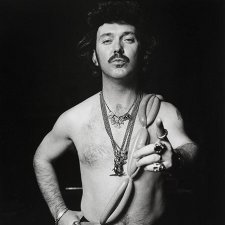

Photographs show the young Arthur as a man with soft features. Aged twenty-one or twenty-two, a slight smile plays across his lips, and his rounded cheeks provide a cherubic counterpoint to the intense look in his eyes. A group photograph from 1945 shows Arthur in his mid-twenties surrounded by friends; his brother David is at his side and his betrothed Yvonne stands behind him, claiming Arthur as her own. His face is gentle and his eyes are shadowed. They are all gathered in his painting studio, and Matcham Skipper holds Arthur’s painted self-portrait aloft for the occasion. Albert Tucker was behind the camera. As Patrick McCaughey recently wrote, the self portrait depicts the young artist as ‘self-questioning’, a ‘perplexed young man’.

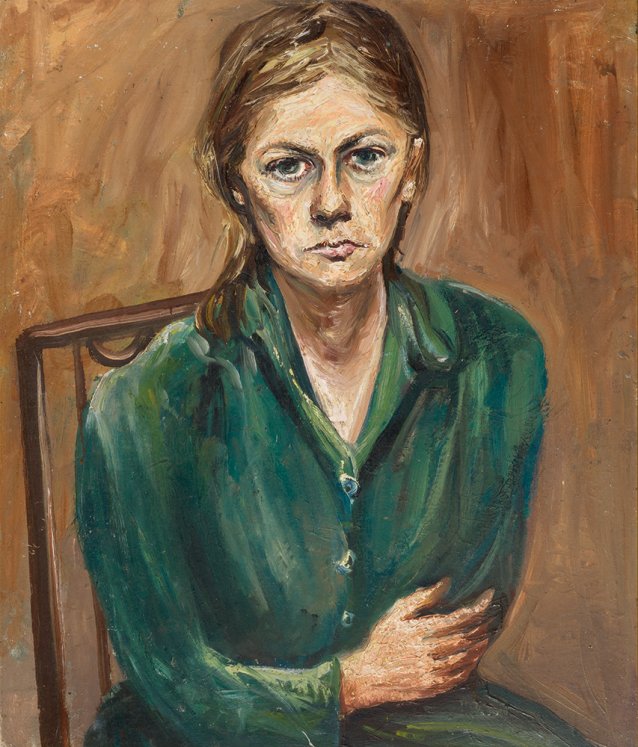

As a boy aged fourteen, Arthur looked intently at those around him. The portraits of his mother and father show his capacity to convey the nuances of his sitters’ psychological and emotional bearing. He had already left school, and, at fifteen and sixteen, turned his gaze upon himself, attempting to manifest through paint on canvas the complexities of his own inner workings. Living with his beloved grandfather and making light-filled paintings of the countryside and seashore, Arthur was also painting those around him. ‘I painted the Driscoll kid’s portrait today’, he wrote to his mother. Written in winter, Arthur’s letter, sprinkled with idiosyncratic spelling and grammar, is intent on reassuring his mother that he and his grandfather are warm and well:

I hope everybody is cosy as can be at Murrumbeena because Gramp and I are as cosy as cosy as cosy as can be, so don’t you worry about us one scrap Mummums. The little flowers you picked are still in their pot on the table and are almost as fresh as the day when they were picked. Well good bye for the present my own sweet dear little Mummums with tons and heaps and heaps of love from your ever loving son Arthur Chook Chooks.