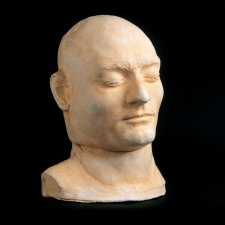

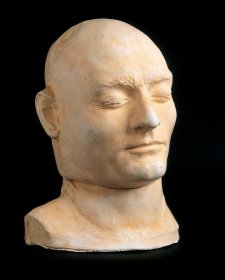

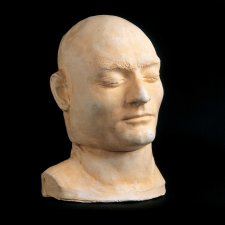

Many famous death masks have been taken of the great and the good, people like Beethoven, people like Napoleon and also of criminals. In a sense they are a marker of this person that is left behind, something that can be analyzed and studied.

The process of taking a death mask involved shaving the head quite soon after the death. It involved putting oil onto the skin and hair to avoid adhesion. The plaster would have been applied to the front. The back would have been taken, and then those two halves are put together to create the mold. They really acquire great popularity during the eighteenth century with physiognomy, and during the nineteenth century with the practice of phrenology.

Phrenology was a practice that was invented more or less by a German physician at the end of the eighteenth century, a man called Franz Josef Gall. The principle was that you could judge a person's intellect and character from the shape of their head. The brain itself was divided up into different parts that perform different functions ranging from love of offspring to tendency to be destructive, violent, to how you relate to god, to how you perceive color and shape, to your love of beauty. The principle was that because the brain pushed against the skull as a person grew up, that therefore the skull perfectly replicated the shape of the brain. By palpating the skull you could understand more about the inner workings of the individual.

If you can't get the real thing then death masks were something that you could use to demonstrate to the audience the pronounced qualities of people whether they were the great and the good or the criminal. There's a sense that they can teach us moral lessons. They can show us what evil looks like, playing into this enduring fascination with monsters, the deviants in our society.

We think of it as a pseudoscience now, it was a science at the time. It was seriously debated by men of medicine, by philosophers. Phrenologists were also by and large opposed to capital punishment because they saw phrenology as a reform science. There was this sense among phrenologists that the practicing poplar performers who were often also great political agitators, that had they been allowed to see Ned Kelly at as a child they might have been able to take steps to rectify these qualities that end up becoming so pronounced later in time.