- So, everyone please welcome Michael Ghillar Anderson.

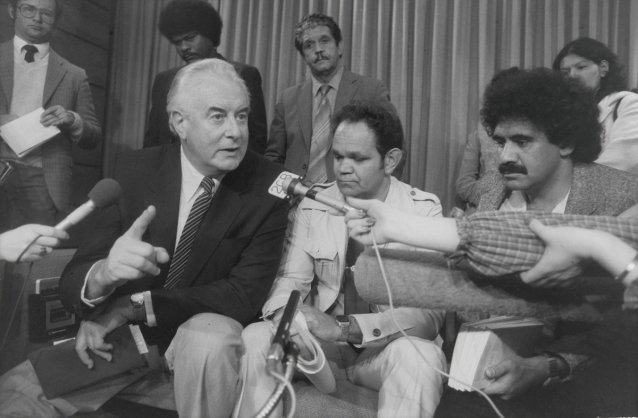

- Thank you. In 1972, the Black Power movement, of which I was part of the Caucus leadership in Sydney, we had relationship with people in Melbourne, Adelaide and Brisbane, who were, I suppose, consolidating a movement to bring to the attention of the world and to Australia that we have a lot of business to complete and deal with. And we must remember that by 1969 in New South Wales, the government, as a result of federal intervention and the success of the 1967 referendum, they took away the mission managers of what we call the prison and I learnt later on, similarly to the Russian gulag because we were a labour force imprisoned within that system and they believed that we were gonna die out peacefully but unfortunately, we've been here for over 100,000 years and that wasn't gonna happen and so we did and we're here and we're fighting. When we set the embassy up we objected to the notion that was put up by Billy McMahon, as a national policy, that they would lease land back to Aborigines and we must acknowledge that prior to that in 1964, '65, the Gurundji had had enough of working for nothing and they walked off the country up there and they walked back to their own country, Daguragu and they just squatted, just like everybody else who took the land off us. They just squatted there and they wasn't gonna move. And that was very successful and that was a motivating factor as well, behind what we were doing as young people who'd just come out out of high school. And we gotta remember that a lot of us who turned up in Sydney at that time, '69, '70, we were all only 17, 18, 19 year old but we had it in our mind that something had to be done. I had arrived in Sydney in '69 to study economics and commerce at Sydney University and there were a number of other young Aboriginal people who already started university. There were some studying law from the Gumbaynggir society, from the Gumbaynggir nation and we worked together. And so these collective minds from different nations, Wiradjuri, Gumbaynggir, Bundjalung, Gummilroi, we pulled those sources of energy together and a brainstorming of these young people from different quarters of the country and of course we knew what we wanted, we understood the bigger picture from our old ones and so we set about doing something about it. When we set the embassy up in 1972, it was quite interesting because we had no idea what to call it and the name came up, Aboriginal Embassy, from one of my colleagues. Now the embassy, people ask, what are the successes of the embassy? Well, first of all, it put the Aboriginal movement and the issues fair square in the middle of Australian society and it made Australian society wake up and take notice and to place it right in front of Parliament House, you couldn't get a better opportunity to draw attention to issues. And of course, I remember Commissioner Osborne coming there with another guy from Federal Police and his deputy and we were sitting in front on the ground in the morning, about seven o'clock and Commissioner Osborn asked the question, what is this? And we said, well, it's a protest and then he said, okay, how long do you intend to be here? And my colleague, Billy Craigie, a Gummilroi man, said, until we get a land right. So here we are 50 years on and we're still waiting and we're still trying to achieve those things. Now, the embassy was very significant and in this picture you see here, Gough Whitlam was the opposition leader at the time and this man paid the honour of coming to us at that embassy. He didn't ask us to come over and meet in Parliament House, he came to where we were and in doing so, he paid that respect to us young leaders and here, now, I've gotta tell you just a little bit about this picture because in this picture, Gough and Paul Kawa is walking out, Pul Kawa was sitting next to the door, I was just coming out behind and behind Gough was a man called Lionel Murphy, who wasn't a little man, by the way. There was another man called Gordon Bryant, who was even double the size of Gough Whitlam and then there was another fellow by the name of Kep Enderby, who was the skinniest out of them all and kept us from the ICT and then there was three of us, sorry, there was four of us Aboriginal people in there. Now, that's a two-man tent. And of course we didn't have the dome of secrecy inside there but we were bulging at the seams, let me tell you. But we sat there in a caucus, in a direct dialogue about what it is that we want. And the thing that Gough Whitlam said that I recall most was the fact that he congratulated us for what we did and said, you guys are very brave doing what you did and you picked out, in our legal system, the weakest point you could ever find and we said, what's that? He said, well, on this lawn here, nobody could move you. There was no law that prevented you from setting up here, no law at all. And so that was quite, like we marked that one down for us. And so he said, so nobody's gonna move you, he said, so we need to keep dialogue and keep talking and of course we had several fun meetings here. That lady standing there presenting is a lady called Faith Bandler. Faith Bandler was the head of the FCAATSI Movement, the FCAATSI Organisation, the Federal Council for Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders and as you see, Gough Whitlam was our keynote speaker on Aboriginal land rights. And here, the first gentleman is a man called Bruce McGuinness, who was leading from Melbourne, he was a very strong leader, very adamant. Young man with his head down passed away just recently, Sammy Watson from Queensland. Then we have Bobby Sykes and moi and there with the curly hair it's all gone now, you may have noticed. Then we had Pastor Robert, who was the head of the Aboriginal Land Right Movement in land council in New South Wales at the time. Then of course there was Gough. Then there was another lady from Victoria, Margaret, not Margaret, that's Mrs. Briggs, Geraldine Briggs, who was a very strong advocate lady. Then we had Mum Shirl, from Sydney, who was a very strong lady for us in Sydney and did a lot of things for us there and of course, then you had Gordon Briscoe, who was a cousin of Charles Perkins. Gordon was there and the man who had the honour of hosting it was a man called Chicka Dixon, who's sitting at the top. And so Gough was always engaged with us in these discussions and we bought the elders down to talk to 'em about this. Sorry, I'm going the wrong way. And so here is Gough, pledging at that time that his government, if he was elected in 1972, he would pursue land right. One thing he did say to us is that the Federal Government could give land rights in the Northern territory and the ACT but he had to enter into dialogue with the states because the states maintain the jurisdiction over land and land matters in the states and so that was a very successful policy change and announcement by the Whitlam government at that time. And here we followed up, during leading up to that election period and this is Gough Whitlam sitting there and then there's, of course, Kep Enderby and I'm next to Kep Enderby with the dark glasses on. Next to Kip Enderby, the man with the stripe, the Aboriginal man, is a man by the name of John Newfong, who was at that time the only Aboriginal journalist in Australia. And John Newfong turned up down there because he'd just got sacked from 60 Minutes, it is the Stone, Gerald Stone, sacked him, only because he employed him to be on the 60 Minutes as a presenter, as a journalist and unfortunately, John went out to interview the garbage strike at Bondi and the garbage men said they didn't wanna talk to the black man, black journalist and so Gerald Stone made the decision that it's no good having you as a black journalist if no one's gonna talk to you, so he lost his job. And so John ended up down there with us and doing that work. This is July, 2072, when we decided that the embassy shall go and we will wait and see what the labour government does for Aboriginal people and so this was the last day, June, July '20. Later in time, 1982, the date there is wrong, by the way, we travelled then I was the director, I was seconded from the Department of Public Prosecution in New South Wales to the National Aboriginal Conference in Canberra, who were the advisory body to the Commonwealth government and they employed me to be the head and director of research to develop a framework for a national treaty in Australia. Malcolm Fraser agreed to that and he sent the documents out and agreed that he would negotiate this treaty with the only elected body in Australia. At that time there were 36 Aboriginal people, men and women, elected from various electors around this country and by popular vote, so they were democratically elected and everybody referred to that group as the Black Parliament in this country. And of course, they worked directly with government in terms of advising policy, and government ministers would write to the organisation, the organisation would consider the policies and the directions that they wanted and we'd correctly advise them on yes or no, this is a good way, let's negotiate this and let's carry on and work out with you. So it was a really good method of communication and negotiations on national issues. When we got to 1981, this was the time when the National Aboriginal Conference nominated a man by the name of WA from Western Australia, I'll think of his name, so long ago, no, no, no, no, Mr. Jacobs, Cedric Jacobs, Pastor Cedric Jacobs. And Cedric Jacobs and I were then nominated to go to the United Nations. The United Nations commenced the process of engaging First Nations people for the first time and so they called a world conference in Geneva, to talk about Aboriginal issues, First Nations issues all over the world and we needed to address these issues, 'cause after all, we'd gone through and had an agreement with the Atlantic Charter, which Churchill and Roosevelt had signed and part of that was to break up the British Empire to begin to give self-determination back to former empire members who were under the rule of the British at the time. And so that was part of an agreement that was entered into between Churchill and of course the most famous statement about Churchill at that time was that, I'm going to be the man remembered for breaking up the empire of Great Britain. And so anyway, that process went but they left out anything to do with the First Nations people, whom they were occupying those countries and they had enslaved them. And so that's the talk and that's the discussion that has been going on since '81 but we're about to reignite the flames and get the United Nations to start talking. We had a very successful meeting the other day, on the 27th, at Albert Hall and the Aboriginal people there and the good thing is that it was elders who made the decision that we are going to set a new path from the grassroots and that's very encouraging. So I just created a lot of work for myself in that. So we made the decision, sorry, I was sent to the United Nations and the Australian government didn't like me going 'cause I was a staff member who was advising Mr. Jacobs and they tried to cancel all my travel arrangements when I got to Canada, because we were meeting with First Nations in Canada on our way through and so they said that, no, you stay in Canada, Michael, you are not to go on to Geneva, you will talk with the Minister for Indigenous Affairs or Native Affairs in Canada and then you will come home. And so when I told the Bureau of Indian Chiefs this, when I had a meeting with the Bureau of Indian Chiefs, all the chiefs from the different nations around Canada were there and so I addressed them and then they said, well, don't worry about it, you don't worry about it, we'll buy you a new ticket, we'll give you money, you go to Geneva. And they actually appointed a couple of their guys to travel with me, they arranged for their Scottish lawyers to meet us in London at Heathrow and I was quite surprised because I thought I was about to be arrested when I got to the Heathrow, because here are these guys in suits but they were Scottish lawyers, barristers actually and they said, oh, we're friendly and we're here to make sure you get to Geneva and the Australian government did everything in their power to stop you from going there. And so, anyway, I landed in Geneva and to my shock, the Secretary of the Human Rights Commission, William Dyers and a group of security people from the UN came and got me out of the aeroplane and showed me all the Australian security guys, who were on the side of the wall at the international airport to grab me and take me into the Australian Embassy if I was on my own and they would take me there, put me on the next plane back to Australia. So they were about to arrest me when I walked out of the airport in Geneva and take me to the Australian Embassy. So that's the story that has to be told and I just told it, because this is how bad the Australian governments are, they just did not want this story out. And then all of a sudden, I can say and I'm honoured that I was the first one to present at the World Conference on Indigenous People at the United Nations in Geneva. Now having done that, that set the agenda then for First Nations people to be talking about the rights of First Nations people who were occupied all over this world and we've got some great discussions that will take place this year with other First Nations people around the world. Then in 1992, so one year later, we're sitting in Sydney and they said to me, Michael, we need to make sure that we get the attention of the British or the Commonwealth heads of government because we're proposing to negotiate a treaty with the Australian government. And so we were sitting in there and I said, all right, why don't we go and talk to the heads of government in some of the key countries around the world that have been liberated and freed from the British Empire and given their self-governance? And I said, let's go to the African Nation States, knowing, of course and that's why that date is wrong, because India was about to host the Commonwealth heads of government meeting at the end of 1982. And so we decided that we would go and then we were sitting there and we said, well, we gotta get someone that the media is gonna take notice of so we can get attention with this trip. And so I'm sitting there and I said to them, let's get Ray né Grace, he's a famous Australian journalist, we get some attention and everyone said, no, he won't do and so I said, well, I'll ring Gough Whitlam up and they said, why? I said, well, I'll ask him to come as a political advisor. I said, that should get us some attention and they said, that's crazy. I said, no, no, he's not a bad bloke and they said, what makes you think that he would come? I said, well, let's put it this way, when I was at the Aboriginal Embassy, I went home, I worked in the cotton fields, Christmas in 1972, we were all camping in tents on the riverbank as cuffs and shippers, earning 65 cents an hour, with over 2000 Aboriginal people working and so I organised a strike because the old people asked me, you black, powerful is no where to do things, we need more wages so I took them on strike after prisoners in 1973. And it took us three weeks and we were in the arbitration court and we won. And we went from 85 cents an hour maximum to 5 dollars 25, an hour, starting immediately. And so that was a people's initiative, that was a grassroots initiative. So all of a sudden Charles Perkins has no mind turned up in this plane from Canberra the next day, after we won the case, 'cause we drove straight home that night to tell everybody and of course they had a plane there, they picked me up after work, I jumped off the track and they said, come, I said, I got no clothes, they said, yes, the ones you got on will do, so we came to town. So they flew me in the Canberra, put me in a nice motel, lend me some money to buy a suit so I can have a meeting next morning and I went into the prime minister's office. And when I got in there, there was him, Lionel Murphy, Kep Enderby, Mr. Blanche, I think it is the deputy prime minister, Don Willesee, foreign minister and Gordon Bryan and I'm sitting there and I said, okay, there's something going on here. I only called him, my pet name was, Alpalo, I said, alright Alphalo what's going on? And he said, Mike, while I'm prime minister, I can have you walk in the streets of Australia and I thought, oh shit, I'm going to jail, that's the first thing to think about. And instead he said, if you're gonna lead your people, well, then we're gonna teach you how it's done internationally. And so we arranged with none other than Mr. Richard Nixon to get approval for me to work in America and I went to the Australian Embassy in Washington, DC, worked in the American State Department and et cetera. So that's flowed from all the stuff that we did with the embassy and the things that I was doing to bring about equality within this country for our people. And I said, from there, I thought, well, he taught me something, so I want him to teach us now a little bit more. So I called his office and I said, what are you doing for the next three months? He said, well, I don't know, it depends on what you want. I said, would you act as an advisor to us if we go on a five nation African tour? What are we doing as we go on over to seek support for the treaty? And at that time, everybody thought that we were going to Canada to ask the black African nation, not to participate in the Commonwealth Games here in Australia and that was so far from the truth, I'm glad we hit that and just had the media frenzy all about that. And so it just shows the media can be silly sometimes and they don't know how to report. But fortunately, the people who didn't like John Newfong as a journalist in the SAC team, they paid for Gough Whitlam to come on that trip and sponsored him on that trip and we had other sponsors to come. As we went through Africa, oh, sorry, prior, when we landed in India, we were met by the foreign office ambassadors, as well as Indera Gandy, who came to the airport to have a half hour conversation with us about why didn't you include me in this conversation because we are hosting the Commonwealth heads of government meeting in 1992? So we gave her a briefing of what we were doing and then we flew on, we give another briefing in Riyadh to the Arabs because their foreign minister came to the airport and hosted us for lunch for about an hour and a half and then we went on to Africa and this gentleman here is Julius Nyerere, the President of Tanzania, a very revered man in African politics. He's a wonderful man and we had discussions with him at the presidential palace, he's the president of Tanzania, this gentleman. We went on to Harare, Zimbabwe and that's President Mugabe and we had discussions with President Mugabe about issues here in Australia. So we had these discussions. We went on to Nigeria and of course in Nigeria they reconvened the parliament for us and we addressed the National Parliament of Nigeria and then had private meetings with the vice president of Nigeria. We then went on to Kenya and met with the prime minister and the governor in Nigeria and spoke about what we were doing on our way. We also met with Ethiopian prime ministers and talked about all the things that we were doing and what we were after in terms of the treaty. So we talked to 'em and we gave 'em a bit of an outline of what we were doing with the treaty and what we were proposing from both government of Australia. And we were about to then put a proposal to the government and Malcolm Fraser said, well, it's time now to start talks with the state governments from a national level, not from just the state. So this was a national approach because the state governments are restricted by their constitutional abilities to negotiate anything. And of course we were pressing that we were only being kind with you guys because we're putting a proposal to you because we're gonna go to England because that's where the power is. Australia sovereignty belongs to England, not the people of Australia. We knew that, that's a legal situation and so we were off to England after we had these discussions to talk with the crown and the parliament in England and arrangements were being made for us to do that. Then all of a sudden an election came, Mabo got in and he finished at all, he just shut it all down and that's another story. So the relationship between Whitlam and the Aboriginal Embassy is one of taking a movement forward. It was one of developing an integrated approach to addressing an issue that is a festering sore now society and it will be until we are mature enough as a nation to begin to start talking about the real issues and the real issues are not just about the deaths and the fact that our people bones are still out there that haven't been buried yet, my mom, for example. We've gone out there and we found the human bone on the open land where the cattle and sheep roam, where they were killed. I've spoken to David Hurley about that. When he was governor of New South Wales, we had discussions at government house. He's now the governor general of Australia so I'm gonna go and knock on his door one day and I'll say, mate, you forgot about that other story, they moved you from there to here. So, I will catch up with the governor general, hopefully within the next six months and be able to sort of remind him because he had spoken with the New South Wales government but the New South Wales government winded on that. And the reason I approached him about this was simply because I said until you guys work with us to help us bury the dead, it's impossible to talk with people who are still mourning and who need closure and then we'll reconcile with you. We can talk about some type of form of reconciliation but until you read yourself from the story of Antigone and help us bury them, then we got nothing to talk about, we're still going to be angry at you and we'll be angry when we do bury them but at least it's a starting point, it's a sign of respect and that's all we're asking for is respect, we're not asking you for much more than that. And so, yeah, I don't know, we have some time, so I suggest that what we do is it would be better for me now to respond to questions because I'm sure some of you might have questions and I think the time now would be best served responding to those questions.

- So while we're collecting some from the audience, we do have a couple from online. And so Anne asks, could you explain some of the limitations of native title and how, if at all, it relates to traditional land tenure systems.

- Oh, okay.

- It sounds like a big lecture actually.

- Well, it is a big lecture but one of the things I've learned about native title and that is the best thing about native title is that itself reconnect the traditional owners to their country. It's also given an opportunity to identify people with their land, where they come from. One of the negative aspects of it is that there're a lot of people because of the way government has moved Aboriginal people from one place to another and situated them over the years, people have developed a strong historical association with land and so native title has created a massive division within the Aboriginal community because they're fighting the same. We've been here for 90 years now, we must have some say and under our law and custom, no, you don't ever say you will never have a say. And this came out in evidence from elders in the Pilbara, in the Karratha native title flame there, when the elders came in and they were talking about the rights of Aboriginal children who were adopted into other Aboriginal families and the elders who gave evidence in that trial, there's about six of them setting another but I'd actually. I've read the transcripts of this and because I've worked over there with them now and develop elders council for them and the evidence that came out was that we can adopt children but the bloodline of those children goes back to their country and they cannot speak for a country where they were raised but they do have a right to go home to their country and speak for that country because that's where their blood belongs, they don't belong to here and so it's quite complex. The other thing about native title and this is so disappointing, is that they always talk about a bundle of rights and everybody talks about what constitutes a bundle of rights? It's certainly not ownership of land, that's what we need to understand here. And when I've looked at the native title determinations that have been made, whether they're consensual or whether they've been litigated, the fact is that when they issue and say, you had now have native title, whether it's inclusive, exclusive land use or it's non-exclusive land use, when you look at the deed and title in the state registry offices, the name of the nation is not registered on the deed and title, no what's registered in the deed and title is USL and USL stands for Unused State Land. So what in the world going on when you can put in a government does not legislate to have the nation's name registered on the land registry? So what's the role of that? I'll tell you one thing that it does do and that is it prevents Aboriginal people from using the land for economic purposes, that's what it does.

- So that sort of leads on to another question that has been posed, well, I think it does anyway. So Michelle asks, could you tell us your views on indigenous land use agreements?

- Wow, yeah, well, just very quickly, let me try and do this as quick as possible because that's another lecture.

- Again, it's another lecture, we could have had a series.

- But I can tell you this, John Howard, when he's made the team fisher, may he rest in peace, when they were running around the country talking about bucket loads of extinguishment, what John Howard did was the trick that we were talking about this the other day and one of our lectures, professor William Paul, was talking to the people and he was talking about troupes and we were talking about how Englishman, in the English language, you have this thing called double speed and in the course they used double verbs, double negatives, sorry, which tricks people in a courtroom. I know that because I was prosecuted. And you use this language and in this language when you use it, it's our language that makes it sound nice but it actually means something else and if you don't know the English language properly, you are tricked into giving away everything. Now, John Howard, on the advice of some people on how to trick the Aboriginals, because after all they pay the lawyers, mostly white, to run these native title claims and so those lawyers the question is who are they working for? Are they working for the people paying them or do they work for the people who they take on as clients? So there's a bit of a problem around just that alone. John Howard, three things that he did, he targeted, how do we get the Aborigines without us telling them, to make legal, all the legal, all the land tenure in this country? And all you have to do is look at the native title of mobile judge decision. If you look at the map by judgement , they say very clearly there that the crown did not gain a beneficial radical title, they gained a radical title. What does that mean? A radical title basically means that in Australia, they set up a registry office. The crown, the king of England or queen of England has never come to this country at all and claim possession, they've never done it, so they don't have possessory title to this country, that's the law and even their own courts have said that in England. Now, in Australia, the High Court in Mabo would say the same thing that Australia, the governments in this country, who were controlling the land jurisdiction, do not have possessory title, which is a beneficial, radical title. They have a radical title but it's a radical title that's a registration only and that's why they set up registry offices and they set up the registry offices based on English, based on the Admiralty law registries within the ship registry, that's why you got people running around talking about Australia is still governed by Admiralty law. Now they use that as a principle to set up registry offices in Australia. So in setting up that registry office gave them a radical title, only it was just a mare colour of title and so they registered the leasers, they registered the surveyed areas of land. And so that did not give the crown beneficial radical title. They now what I've seen many legal advice to government where they say, if every unit run a case on the question of beneficial radical title and win that case, every ounce of gold and silver, the royal mineral, that's ever been found in this country will have to be repaid back to the Aboriginal people who own that land where that gold and silver came from and I know they're panicking about that. So we have this understanding, we have this legal understanding and the High Courts of Australia have in fact reinforced what was already said in the 1830s and 1840s by supreme courts have be set up in this country. And so the issue of land with Aboriginal people now, John Howard said, well, okay, part of it is if you sign this in your indigenous land use agreement, you are approving pass backs, you're validating pass backs. Now in the Mabo decision, the Mabo decision said that Australia's land title was a tenure of some kind. The High Court, the full bench of High Court, could not identify what type of lenting exists in this country that extinguishes Aboriginal rights to land now and so the High Court left that open, that's still an outstanding question. The other point that John had, so John Howard's asking Aboriginal people without explaining to them, what type of land are we validating? And how far back does it go? Because he knows, everybody knows in this country, all those legal people anyway, at that high rappy and government, know that they do not have legal title to this land and this is where everything gets a bit fuzzy because all the politicians got weak in the knees when you start talking about it. Now, the other thing is there's also an intermediary, there's a class day where they asked you to validate the Intermediary Act. The Intermediary Acts is all the crown land that they gave you so to other people, farmers, they let 'em take over the stock routes, they let 'em take over the town commons and et cetera. Now all of these places under the law of Australia are now subject to claim by Aboriginal people and so they give them these short-term leases, the farmers and they've allowed them to extend their farms to take in these top grounds and those top grounds are subject to be claimed but they now form part of a compensation package and that's a massive, massive amount of money that the government will have to pay to Aboriginal people because it's happened after 1975, when the Racial Discrimination Act came in. And so everything that the government have done since then they have to pay compensation for if Aboriginal people have the capacity to claim native title. Now all that title land tenure that was there previously is still yet subject to negotiation and we're gonna get there and the other third element of the pinpoint plan was to authorise Aboriginal people, to authorise future acts, that is local governments and governments, development on lands, in the future, if Aborigine sign those indigenous land use agreements, they're signing away their rights to their grandchildren to negotiate on development on Aboriginal lands in the future and so that is when you read the act, it reads that the future act is to be classified as past act. So again, it's cheating and the Australian public don't know this. And so just on the compensation aspect, John Howard was very careful about this because there was an experience where Zimbabwe had entered into an agreement when John Howard went ballistic in Australia, when Robert Mugabe was gonna sign all those laws in his government to take away land off non native people of Zimbabwe and the world was in uproar and John Howard opened the doors for all the Zimbabweans to come to Australia, the white Zimbabweans and you wanna free yourself from that tyranny of that black man. And then believe it or not, they all came here under British passport. Same as when South Africa was liberated, they all travelled to Australia, not on South African passport, they were given citizenship by Britain very quickly so they can come to Australia as British subjects, they didn't come as South Africans, Africana. So when that happened, England had already done a deal with Mugabe under the Lancaster Agreement in London to make money available so that they could then buy these farmers out in Zimbabwe. And it's important for the public to know that most of those farms in Zimbabwe, as it was all Rhodesia, were all soldier settlement grants, majority of them were soldier settlement grants. After the First World War and Second World War England gave 'em some money and the south part of the soldiers agreement grant and they granted these farmers these farms for their services to the British king in the First World War and later in the Second World War. So they gave 'em all this land. So that was soldiers settlement grant. And I've been to Zimbabwe on several occasions and they've taken me around the country and they showed me where the farms were and then how they rounded up all the blacks and put them all in the middle and so you had these villages in the middle and then the farmers could come in and get them and use them for services. Very clever. And John Howard by the way, interfered with that, when they started saying, we're gonna take land off of the white farmers and John Howard said, no, we want England to stop that money so that you don't keep all the white farmers out of Zimbabwe. So John Howard messed up a little bit and interfered with another nation's business. So, there's a lot that's gone on that the Australian public they're not aware of. So that's my short answer.

- So one question which sort of is that, do you have a call to action for Australians everywhere? How can we be allies in a useful way?

- That's a very good question and on the 27th, when we had the meeting at the Albert Hall we put together, I've asked people to come together so that we can have a black-white caucus and it becomes a think thing of going forward. Now, a lot of the Aboriginal elders who were there, they've gone home now to organise meetings with their people, their nations and they want me to come and sit and talk with them but we can't do that alone, we need to take everybody along, including our own people. We need to take everybody along so that we have a very good understanding of how we can fix it up. If we're gonna rely on the politicians, nothing's gonna happen, they just kind of cause confusion and muck up and we get lost in everything. So we, the people have to make this decision and we the people need to work together. And what happens there is if you take out the blame game. We can't afford these days, at this time in history for people like myself, who I hope got another 50 years in but the fact is that we should start now because we have people with the knowledge and who are prepared to talk and who have gone through the row. We either been a racist or we report against them or I'd been racist against the whites and I must put my hand up to say that because I didn't like some of the farmers, some of the irrigators. I still don't like them but I'm gonna talk to 'em, not because of them personally but because of what's being done to the land and so we need to come together and I think if we develop a Corpus outside of government, let's get away from government, because they are useless in this situation.

- And so, you mentioned earlier that there're tensions between different Aboriginal groups, can you see a way forward for that? Like if everyone's coming together and talking, is that what you wanting to happen there?

- Just on that point, the mistake that's been made in this country is that they thought we were all gonna die out and so they rounded us all up and pushed us away, took the children away and never thought that those children would ever ask questions later on and want to find their way back home. Now in doing this, I go back to a 1946 statement by Lieutenant Colonel Bruxner in the New South Wales parliament, when they were going from the Aboriginal Protection Board to change it to the Aborigines Welfare Board, in that debate, the Lieutenant Colonel Bruxner said that we have done a major wrong to the Aboriginal people by removing them from their homelands and by moving them from their homelands and taking them to Farrow places. Like, for example, the Nimba people and the Ayyappa people from Barog in central New South Wales, they rounded all those people up from where they were all congregated, where they lived, centrally there and they relocated all those people, majority of them, to Menindee and then they moved them onto someone else's land, other people's land and they set up this big reserve there and they wasn't allowed to live from there. And so the people didn't move either and a lot of the elders, because they'd moved off they're dying and so we didn't have the wisdom of that leadership to show who we were. And so nowadays people like my mom, Angledool my mother, my people come from Angledool. We have the record, Thomas Mitchell putting a sign up where my family were, my ancestors come from on the Narran River, that man met my mom there it's in his journals but then they congregate, put a wall on an Angledool mission and then when the war broke out in 1936, '37, 1936, they picked them all up. My mum was three year old and they transported them 200 kilometres away to the war now. And so we got down there and then all of a sudden they brought the people in from Menindee by camel, they brought them in from, not Menindee, they brought him in from Tibooburra, Monering, out in the desert area and they relocated them all into Brewarrina. And my old ones told us how they used to fight with each other all the time and they hated each other and then all of a sudden marriage systems broke down and then young man ran off with a woman wrong way and so those people were banished from their own families because they were running away with someone else. And so we have to live with that now because the old people passed on, don't trust that mobile buddy, that's not their bad mode, this is not good mobile. And so inside our nations now, inside our communities, we still deal with that and if you really wanna prove that point lock 'em in one pub, then you'll see the difference. And so there's a lot of undoing to be done within ourselves. We have a lot of work to do. The thing that the Australian government is doing currently is not paying heed to what happened in the United States, in Canada. In Canada and the United States, at least they knew the different names of the tribes, the nations and they did deals with them, they treated with them because all fought against each other and records show our people fighting against them as well. Don't worry, there's a lot of bloodshed out there on defending against the free settlers, as well as the soldiers to back them up and up and the police later on. But the fact is that the people know who they are and because of the historical oppression on the way in which the government have manipulated our lives, we're still sorting that out. So what we need to do is we need to pay respect to the fact that there're nations there now and Australia has taken that step by acknowledging country and when you acknowledge country, you have to find out who the true people are, the traditional owners and quite frankly, there's a lot of fights over who should be welcoming people to country. And the other thing about welcome people, ask me to welcome people to country, I say, no, I don't welcome people to country, simply because we haven't fixed it up yet. I'll tell you the story about my country but I won't welcome you onto my country because we haven't got it fixed up yet. And the thing is if you look at the legalities around that as well, the moment I welcome you onto the country, I'm acknowledging your presence and your authority some degree and so now the authority is mine, that's my country. You should be asking me, can you come onto the land? I shouldn't be welcoming you, you should be asking me permission to come to my land and talk to me. And so yeah, they're minor things but they are large in the scale and they're matters that we have to deal with.

- I've been formally elected as the chair of the Northern Basin Aboriginal Nations Group, which consists of 22 nations across the Southern portion of Queensland, which is a Northern part of the Murray-Darling basin and also the Northern part of New South Wales, right from the mountains, right back to, I think the Woriga in Piru. Now what we have is that we have been discussing and I'm negotiating a new contract, as a matter of fact, next Friday, with the New South Wales DPI, to pursue floodplain harvesting issues and so we will be talking about that. We're gonna be asking the parliament to lobby them to sort of not pursue the new approach that they're taking on floodplain harvesting in New South Wales, because we need to talk more about it. They're going to give us an opportunity and time to talk about floodplain harvesting in New South Wales and we see it as a major threat to the ecology, to the natural ecological system. We have a lot of wetlands out there that only gets watered when the big floods come or when we get the heavy rains and the runoff. There's a lot of illegal structures that we've been finding within that Northern system and particularly the Northeastern system, where there are illegal structures that are stopping water running and that's cutting off, what they call inconsequential flows, where the water from the rainforest runs into the river and then we get a small flush down the river system. Now, if they're gonna do floodplain harvesting, it's not just about the big floods when the floods come across the country, it's about that rainfall as well and then not telling the us about the rainfall and we're focusing on that rainfall because those rainfalls help keep that system alive and if you've got people there catching the rainfall, that comes through those riparian zones and creeks, then they don't get into the river system. The other thing that we're extremely concerned about with the floodplain harvesting as well, is the fact that they're gonna store things there and if we get that big systems coming through and then you've got the farmers with the pesticides and herbicides that are going into that land, that gets into the river system and now we don't know what sort of concussion there is. I know the scientists do 'cause they've done the work in the Murray-Darling basin but they're not telling us. And so if you look at the rivers, a lot of the rivers don't have those natural reeds that's in the river system that used to be there, they're all gone. There's little mussels that used to be in that river, they're dead, there's little snails that used to be in those river systems, right along the river, they gone, they're dead. Why are they dead? Because that stuff has killed them. And so we need to do a complete reexamination of the farming techniques in Australia. Now they tell us on TV all the time that they're modifying their systems and how to do it but yet at the same time, they're clearing massive areas of land and we are concerned about that because everybody's the loser here. The farmer is the loser, the irrigators are the loser and I'm trying to talk to the MDBA about adhering to the convention on desertification. And if you look at the desertification that's happened around the world, in other places where they've corporatized water, the women are the ones and the micro businesses, micro industries, that the women in those countries they've lost that ability, they're starving now, they lost their micro industry. They're the ones who were producing the food, they're the ones who were keeping the children alive, they're the ones who kept those industries going and feeding the nation from those small micro industries. Because they corporatize the industry now water, those women they've lost their power and lost those little micro industries. In Australia I can see that emerging, we have great concerns. I've gone back to a case called Wilson vs Anderson, I'm the Anderson, right? John Howard ran a test case on native title. I figured the 10 point plan and it was more to do with, what is the position of the soldier settlement grant rather than anything else? But one thing emerged out of that and the question was asked of the High Court, okay, so who owns the land in the bed of the river when the river is dried? And so, as it turns out, the farmer actually owns the bed of the river, the soil in the river. That's what the High Court decided but they separated the water that flows through the river and said the farmer does not own that water, that's just something else that flows through. So it reminds me of a thermometer, with that thing in there, what do you call it? Mercury, yeah? And so I keep thinking about the mercury, up and down all the time, the temperature and of course now we've got a river system where the farmer owns the bed but he doesn't own the water that runs through. So what they've done is that they've defined and courtesy, John Anderson straight after that High Court decision, John Anderson went into action and they began to privatise border and separate water from the land. And if you look at the Lord at the Commonwealth Theatre they introduced, they then translated that into the state regime, where they can privatise the water and so they privatised it. And unfortunately, it's the people in the farms out there, the graziers association, the local towns, where there's weazer, they're the ones who were suffering, us, were suffering and our new regime, because we're rebranding the Northern Basin Aboriginal Nations and we're rebranding and we've already made that start and New South Wales now wants to renegotiate with us, a new contract with us. We're going back to Queensland and saying to the minister, we can all have a big clash that's gonna be a nasty one or we talk and let's be civil, let's be mature enough to talk. Because when we approved the Queensland a water resource plan, because under the Commonwealth Act it has to come through the Northern Basin Aboriginal Nations group and so we sat with them and unfortunately and I now found out that we'd been misled into saying that we couldn't talk about the content of the plans, we can but we haven't but now we found out that in Queensland when we were talking to the government about the plans, we asked them the question, well, where's the water for Aboriginal people that we can start talking about our share within the river system? And the Queensland government looked at us and just said, oh, there's no more water, we validated it all, in every system and we looked at 'em, we said, well, you want us to approve that? And they said, yeah. So, yeah, it's a nasty piece but we are working now and with your organisation we will be in touch with the farmers and graziers and irrigators and we want to have those discussions face to face so that we take it out of the government hands and we come up with an agreement between ourselves and we will treaty with each other because there will be private treaties and we will go to the government and we say, this is how it's gonna work.

- We're just gonna take a short pause because we actually are still streaming to our online audience and we're going to say goodbye to them 'cause we do need to close that down but feel free to stay here on site. So thanks everyone online for joining us today. Just so that you know, there was over 100 people joined us from across the country so that's terrific. Thank you and hopefully see you online again soon. Thanks.