- About us

- Support the Gallery

- Venue hire

- Publications

- Research library

- Organisation chart

- Employment

- Contact us

- Make a booking

- Onsite programs

- Online programs

- School visit information

- Learning resources

- Little Darlings

- Professional learning

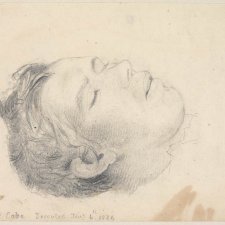

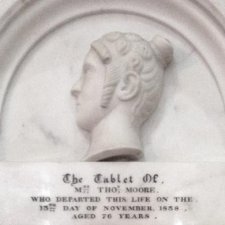

Desperately seeking Woolner medallions

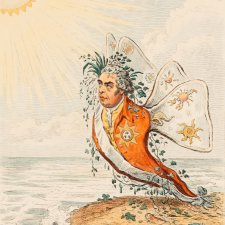

The caricaturist and engraver James Gillray's biting satires about Sir Joseph Banks.

Just after 10.00 o'clock on 3 December 1879, four prisoners were brought from their cells at Darlinghurst Gaol and placed in the dock of a courtroom heaving with agitated spectators

Tennyson's Enoch Arden was inspired by a story that Thomas Woolner passed on to him – but whose story and of whom?

Just now we pause to mark the centenary of ANZAC, the day when, together with British, other imperial and allied forces, the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps landed at Gallipoli at the start of the ill-starred Dardanelles campaign.

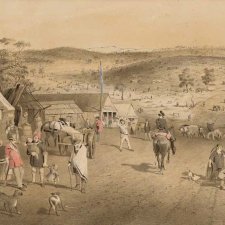

In recent years I have become fascinated by the so-called Sydney Cove Medallion (1789), a work of art that bridges the 10,000-mile gap between the newly established penal settlement at Port Jackson and the beating heart of Enlightenment England.

It has been suggested that Sir Thomas Brisbane’s interest in the New South Wales governorship was as attributable to his passion for astronomy as to the desirability of the position as a prestigious career move.

The National Portrait Gallery mourns the loss of one our most generous benefactors, Robert Oatley AO.

The life of William Bligh offers up a handful of the most remarkable episodes in the history of Britain’s eighteenth and early nineteenth-century maritime empire.

James McCabe provides proof that hanging wasn’t necessarily a fate reserved for the perpetrators of murder and other deeds of darkest hue.

Beyond the centenary of the ANZAC landings at Gallipoli, a number of other notable anniversaries converge this year. Waterloo deserves a little focussed consideration, for in the decades following 1815 numerous Waterloo and Peninsular War veterans came to Australia.

Emily Casey takes in Shirley Purdie’s remarkable self-portrait, Ngalim-Ngalimbooroo Ngagenybe.

It may seem an odd thing to do at one’s leisure on a beautiful tropical island, but I spent much of my midwinter break a few weeks ago re-reading Bleak House.

One of the chief aims of George Stubbs, 1724–1806, the late Judy Egerton’s great 1984–85 exhibition at the Tate Gallery was to provide an eloquent rebuttal to Josiah Wedgwood’s famous remark of 1780: “Noboby suspects Mr Stubs [sic] of painting anything but horses & lions, or dogs & tigers.”

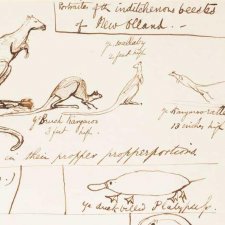

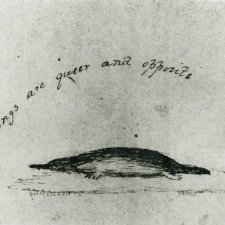

A remarkable undated drawing by Edward Lear (1812–88) blends natural history and whimsy.

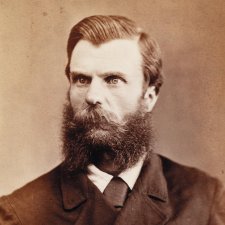

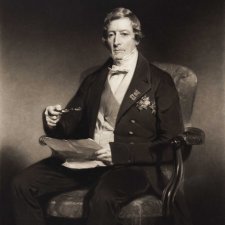

To celebrate his family bicentenary, Malcolm Robertson looks at the portraiture legacy left by his ancestors.

The southern winter has arrived. For people in the northern hemisphere (the majority of humanity) the idea of snow and ice, freezing mist and fog in June, potentially continuing through to August and beyond, encapsulates the topsy-turvidom of our southern continent.

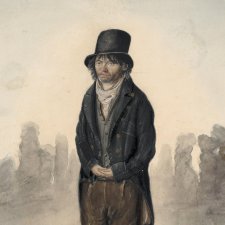

Those of you who are active in social media circles may be aware that through the past week I have unleashed a blitz on Facebook and Instagram in connection with our new winter exhibition Dempsey’s People: A Folio of British Street Portraits, 1824−1844.

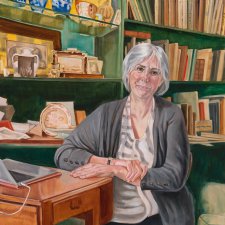

Inga Walton sheds light on a portraiture collection usually only seen by students and teachers at Melbourne University.

Some years ago my colleague Andrea Wolk Rager and I spent several days in the darkened basement of a Rothschild Bank, inspecting every one of the nearly 700 autochromes created immediately before World War I by the youthful Lionel de Rothschild.

There is in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut, an English painting, datable on the basis of costume to about 1745, that has for many years exercised my imagination.

This is my last Trumbology before, in a little more than a week from now, I pass to my successor Karen Quinlan the precious baton of the Directorship of the National Portrait Gallery.

At first glance, this small watercolour group portrait of her two sons and four daughters by Maria Caroline Brownrigg (d. 1880) may seem prosaic, even hesitant

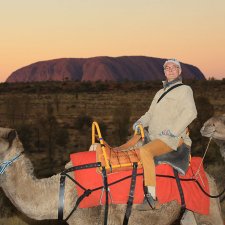

Angus' initial perception of Uluru shifts, as he comes to see it as central to the entire order of Anangu life.

Where do we draw a line between the personal and the historical? Although she died in Melbourne in 1975, when I was not quite eleven years old, I have the vividest memories of my maternal grandmother Helen Borthwick.