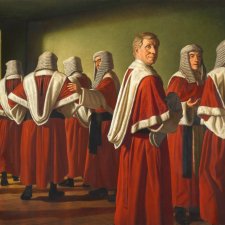

On Monday, 29th May 2000, Barbara Blackman donated to the National Portrait Gallery a portrait of her close friends - poet Judith Wright, her husband and philosopher Jack (J.P.) McKinney and their daughter Meredith.

The unique family portrait painted by Charles Blackman, had been missing since 1961 and it gave Barbara great pleasure to donate the portrait to the gallery. The occasion also celebrated Judith's 85th birthday and Barbara used the opportunity to present a tribute to her close and cherished friend.

Judith

I met Judith first when I was in my penultimate year at school, Brisbane State High. She was fifteen years older than I, awkward, shy, confident, poetic. A group of students a couple of years ahead of me at school, spurred on by the contempt of the Principal, had started up a Magazine for Creative Youth, called Barjai, which printed the poems, stories, essays on politics and education of a young avant garde. They held Sunday afternoon meetings, very cooth, in the Lyceum Club rooms, read their new work to one and another and invited significant speakers.

Judith had her unpublished manuscript of The Moving Image and read us her poems. They went to the heart, the Australian heart. Our friendship began. It was not just that she was a poet, deposited the crystals of her poems, it was that she believed that the saddest thing in the world was that people lived unpoetically. Poems were not just those printed words that sang and danced upon the page. It was that poems are a way of perceiving the world, and oneself. I thought I was a poet and wrote a lot of it. She explained to me that I was not a poet; I was a person to whom poems happened. That is enough. For me, always, Life is a poem, a poem forever being extended.

Then there was Jack, J.P. McKinney, published writer, who spoke at a 'Barjai' meeting sometime later. He was the age my father would have been had he lived. Jack with his white goatee beard, keen blue eyes, direct, disarming manner, spoke to us about emotional honesty. I had never heard of such a thing. I felt I wanted to listen to everything this man had to say. Indeed Judith and Jack became my Sky Heroes for ever after. We used to go sometimes for weekends to their little wooden house made of books on the long red road at Tamborine, gentled by Judith's readings and comments and bluff country meals, pricked by Jack's exposure of the Modern World Crisis and warmed by his worldly humour and the legendary anecdotes of his roving days in the bush. When disappointed at the degree end of my Philosophy and Psychology university studies, I found Jack and Judith to be my real teachers, Judith reading me Jung, Jack probing the philosophic sources.

Charles, in his quite different way, was just as engaged with them both. For one thing, both men were of a small wiry stature, and had quixotic deviant personalities. They once dug a deep hole lavatory drop together, an aviary of words flying between them. Jack's favourite swearword was 'You you you bikwitters!' Judith was always as deaf as I was blind- halfway there when we met, latterly to conclusion. Jack would sometimes humour the situation by shouting to me and ushering Judith forward by the elbow. The banner they held high between their two poles was an absorption in the Australian landscape and an understanding of the Australian personality on the one hand and a pervading sense of the weight and worth of words on the other.

In the 50s when we Blackmans lived in Melbourne and the McKinneys lived on Tamborine Mountain, we went often north for the winter and stayed in the new house, Calanthe, and often they went off in the blue panel van to their hideaway at Boreen. On such occasions we fed the chooks, ate the eggs, walked the roads, read the books. Charles ruthlessly decomposed the writing room and made it a studio, spreading table-sized sheets of paper three foot by four foot six and painted on them, sometimes cutting the paper in halves to make verticals thirty six inches by twenty seven.

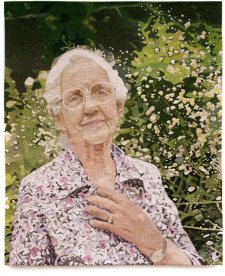

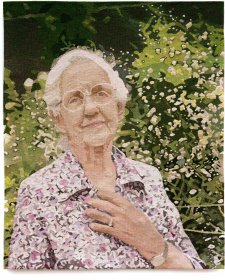

In winter 1955 we all went for a picnic down to Cedar Creek. By this time their cherished little daughter was five years old. It was a gorgeous happy day. Charles took a photograph with his 'Brownie' and I have used it in my book Glass After Glass. Later he painted that scene, kindly clothing dear Meredith, and before they took off north, did half-size portraits of Jack and Meredith. This was a short year before he began painting his Alice in Wonderland series.

This painting, forgotten, turned up for re-sale in a Melbourne gallery. Felicity Moore, curator and authority on the work of C.B., sighted it and phoned me at once, not to miss this opportunity. So 1 acquired the painting for the purpose of enshrining it in this Gallery. In my younger days, when I was given to writing letters to the papers telling how the country should be run, I strongly advocated a National Portrait Gallery - and here it is. And here is Judith, my good, dear, beloved long friend, achieving her eighty fifth year to Heaven. And here is a Currency Press books of Queensland play's including Jack's Well. And here is Meredith back in Australia from Japan and just having put to the test her mother's observation that 'when one turns fifty, the shadows are all on the other side of the mountain', by venturing just this month past to climb up and over a sacred mountain in Japan.

A little diversion. At our study place called 'Yindooroopilly', on the first weekend of December 1996, we had a Study Weekend to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of Jack's death. We called it 'Pin your ears back Jack, we're talking about you.' We read passages from his 'Structure of Modern Philosophy', from his prize winning First World War novel, The Crucible and we tried very hard to read Jack's play without cracking up into fountains of laughter at every other line. Salute you, Jack, o great heart!

It gives me great joy to present this painting to this gallery, to commemorate the poetry of Judith's life and the great gifts she has given us with words, to celebrate Jack, and Meredith too, the fruits of whose scholarship are in the ripening. I thank Andrew Sayers for receiving our gifts.