Many of Leutwyler’s subjects, however, are not famous: they are just as likely to come from her circle of friends. These are people that, to borrow a term from the artist Amos Gebhardt, are engaged in ‘small acts of resistance’ but for Leutwyler are just as valid and important. ‘Queerness,’ Leutwyler believes, ‘is an ever-evolving concept that thrives in the diversity and complexity of human experiences. It resists being confined to fixed definitions and invites individuals to explore their identities and desires authentically.’ People living their lives with courage and (often through trauma and difficulty) coming to a place of empowerment and truth. There is an egalitarianism impulse here. When I asked Leutwyler who she considered the most important living artist, she answered ‘in all honesty it’s probably someone’s great aunt’s neighbour’s cousin (once removed) whose work will never be known to us’. (She then named Ai Weiwei, for his ‘willingness to confront censorship and authoritarianism, his commitment to social justice’ and the way his artworks ‘compel viewers to confront uncomfortable truths and question societal norms’.)

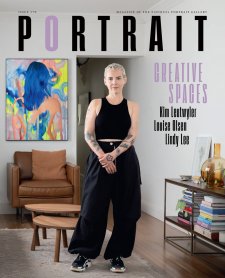

Leutwyler engages with ethical considerations throughout the art-making process, from the materials she uses (oil, despite her love of acrylics, which leaves virtually no waste as opposed to plastics entering the waterways) to the people she chooses to paint, those she admires and has been impacted by, raising the profile of queer people in a way that leads to open dialogue and action when she releases the finished portrait into the world. There is respect and care here, an engaged enquiry into the ethics of looking, an acknowledgment of and commitment to disrupting the objectifying gaze, which through the history of western visual culture has been an overwhelmingly male one; as Leutwyler notes, taking ‘pleasure in subverting traditional norms of portraiture to challenge heterosexual conventions of identity and sexuality’. A commitment also to seeing on the walls of major galleries portraits by a queer woman of queer women, gender diverse and trans people absent or erased from the historical narrative and still wildly underrepresented.

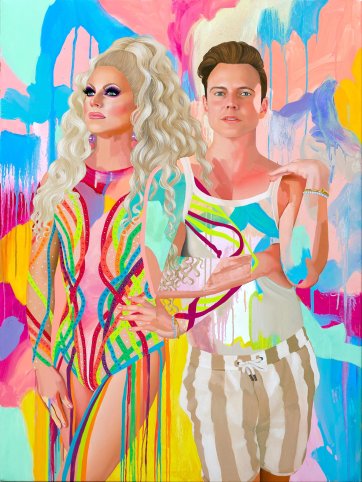

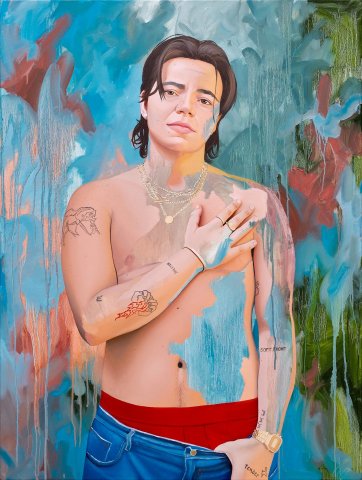

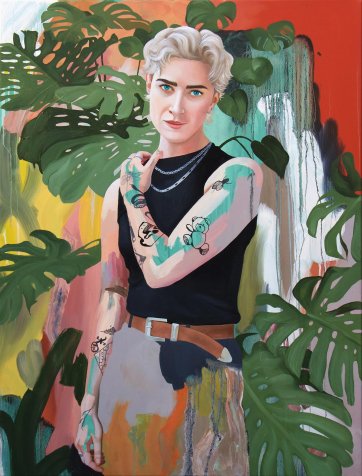

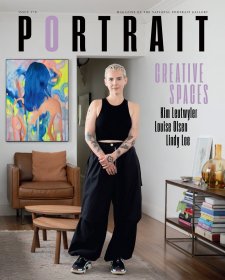

Sitters have self-determination over how they will be depicted. Perhaps not surprisingly those in the public eye often choose to be depicted clothed (the exception here is non-binary, transmasculine actor Zoe Terakes, known for roles in Nine Perfect Strangers and Wentworth, who proudly takes their shirt off to display their gender confirmation surgery), but many of Leutwyler’s sitters do not. Her project is deeply engaged with questions of the construction of gender and identity: how that is signalled to others in the queer community through the body and specific choices about ways of being and being seen – through androgyny, body art, symbolic tattoos, piercings, leatherwear. All build a sense of belonging through specific ways of constructing identity, reflecting the position that the body is both a political and personal site. Leutwyler has made a number of self portraits in which she herself appears naked – if she puts her community under the lens she is willing to turn the lens on herself.