Portrait of a Pioneer , 1917.

Violet Teague. Castlemaine Art Museum.

Gift of the artist, 1940

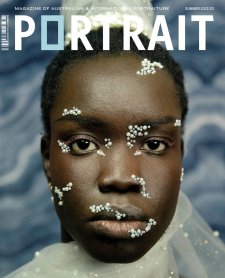

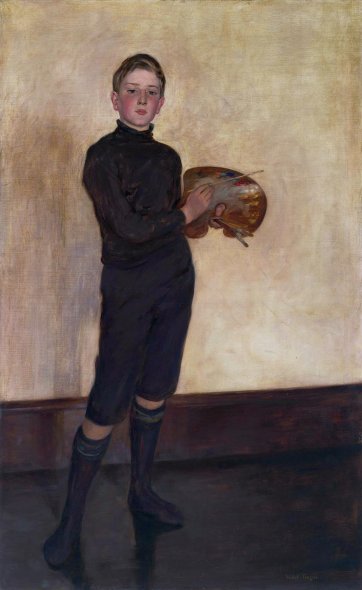

In late 1921, artist Violet Teague held a solo exhibition at the Athenaeum Gallery in Collins Street, Melbourne. Launched three months before her 50th birthday, the exhibition was effectively a retrospective, with examples of her student work on display alongside landscapes, seascapes, woodcuts and genre paintings, and the recently completed The Adoration of the Shepherds, an altarpiece Teague created for the Anglican church at Kinglake built in memory of the locals who’d died serving in the Great War. Some reviewers were especially taken with the latter, a nativity scene in which traditional shepherd figures were supplanted by two uniformed Australian soldiers kneeling before the infant Christ. As more than one reviewer pointed out, however, though Teague was ‘an artist of the versatile type’ she was ‘before all things, a portrait painter’, and her 1921 exhibition was just as noteworthy for the inclusion of many of the portraits that had earned her significant accolades over the preceding twenty years. There was The boy with the palette, a full-length portrait from 1911 of Teague’s twelve-year-old painting companion Theo Scharf. He was something of a prodigy in music and art and it shows in Teague’s picture: a cocky lad in knickerbockers and a roll-neck jersey, looking as if he thinks the artist should feel privileged to be painting him. Others included a 1901 portrait of Teague’s stepmother Sybella, ‘a bold and meritorious study in black’ evoking the style of James McNeill Whistler; and Cynthia and Count Brusiloff (1917), also known as England, Home and Beauty, a satiny homage to the celebrated eighteenth-century British painter Thomas Gainsborough. Each over six feet high, these paintings are taller than Teague herself was, but she claimed to prefer seeing ‘the whole of my sitter, for I think there is as much character in the hands and form as the head’.

1 The boy with the palette, 1911

Violet Teague. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

Gift of US Teague 1976. © Violet Teague Archive, courtesy Felicity Druce. 2 Cynthia and Count Brusiloff , 1917 Violet Teague. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased, 1954. Photo: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Teague had first been touted for her ‘fine, vigorous work as a portraitist’ while a student at the National Gallery of Victoria School in the 1890s, and during the succeeding decade she was frequently singled out for her technical flair and ‘wonderful power of expressing the character of her sitters’. Born in Melbourne in 1872, she’d received early tuition in drawing as a schoolgirl, but didn’t undertake what she termed ‘serious work’ in art until she went to Europe with Sybella in her late teens. ‘I was travelling with my mother,’ she explained in a 1901 interview, ‘and as it was always intended that I should have more drawing lessons, it was thought a good opportunity while we were in Brussels.’ She had some lessons at the atelier run by French painter Ernest Blanc-Garin, and then ‘begged and prayed to be allowed to continue’. She remained abroad studying for the next few years, mainly in Brussels but also at the school run by the German-born social realist painter Hubert von Herkomer in Hertfordshire, England. While overseas, Teague saw ‘the galleries at Berlin, Dresden, Paris, London, Bruges, Amsterdam and Rotterdam’, and had memorable encounters with portraits by Gainsborough. ‘I know no one before or since who could so paint the veined rose-leaf of a child’s lip, its very texture; or the grace and spontaneous charm of English gentlewomen,’ she said of Gainsborough in a lecture she delivered to her old school, Presbyterian Ladies College, in 1925. Equally as memorable were the paintings she saw on her first trip abroad in 1884, when her family holidayed in Spain and Portugal. Teague recalled being especially struck, as a twelve year old, by certain paintings she saw at Madrid’s Museo del Prado, including works by Raphael, Titian and Anthony van Dyck, and Spanish masters such as Diego Velázquez.

1 Portrait [Sybella Teague], 1901

Violet Teague. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased, 1959.

Photo: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. 2 Portrait of Millicent, Duchess of Sutherland , 1904 John Singer Sargent. Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. © Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

Traces of the effect that Gainsborough, Velázquez, Joshua Reynolds and other exemplars of the grand manner had on Teague are evident in the full-length portraits she started making a few years after she established her own studio in Melbourne in 1895. Unmistakeable too is evidence of the impact of Whistler and John Singer Sargent, the expat American superstars of Gilded Age art, who influenced a generation of portraitists in their homeland and elsewhere, Teague being one of a notable group of Australian exponents of their swaggering, painterly style. Though often thought of as the greatest portraitist of his era and the go-to painter for Society on both sides of the Atlantic, Sargent was in fact a key figure in the transition from the old century to the new in painting terms, creating a method by which something as traditional or as moribund as a grand society portrait could accommodate innovation, modernity and psychological insight. Sargent took the learnings he had himself acquired from artists like Velázquez and the great eighteenth-century English painters and combined them with what his friend Henry James called a ‘faculty of taking a fresh, direct, independent, unborrowed impression’. In Sargent’s portraits, sumptuously dressed socialites loll, urbane gents smoke or stride or look askance, children look bored or quizzical, forthright women return your gaze with confidence, or deign to look your way at all.

Fresh, direct, independent. These are words that might easily be applied to Teague, who was well-travelled, wealthy enough to eschew marriage and, despite her conventional, affluent upbringing, remained as singular in her life as in her work. Without needing to make a living from her art, she could take or leave prevailing tastes and explore an eclectic range of mediums and subjects. ‘She painted landscapes, but they were never aggressive geography lessons,’ art historian Joan Kerr explained. ‘Nor were they big productions aimed at gallery trustees and rich buyers. Her painting techniques were neither old-fashioned nor avant-garde but fascinatingly complex.’ In terms of portraiture – commonly scorned as a purely money-making activity – this creative independence meant that Teague didn’t have to chase commissions and could choose who she painted and how she painted them. She could make a work called Portrait of a Pioneer without making yet another image of a gnarled, bearded bloke in a scorched or forbidding landscape setting; and create a group portrait of the Chirnside family in the form of ten diminutive individual pictures grouped together on a single cedar panel. Usually, she made portraits of family, friends and acquaintances, ‘pursuing portraiture as a personal vocation’ and her ‘preferred means of artistic expression’, as curator Virginia Hammond wrote in 1992. Teague wasn’t one to ‘flatter her sitters or endue them with graces and beauties not their own’. Instead, she employed a mix of ideas, influences and techniques to arrive at an approach which was adaptable, as art historian Richard Neville has observed, to different purposes and subjects.

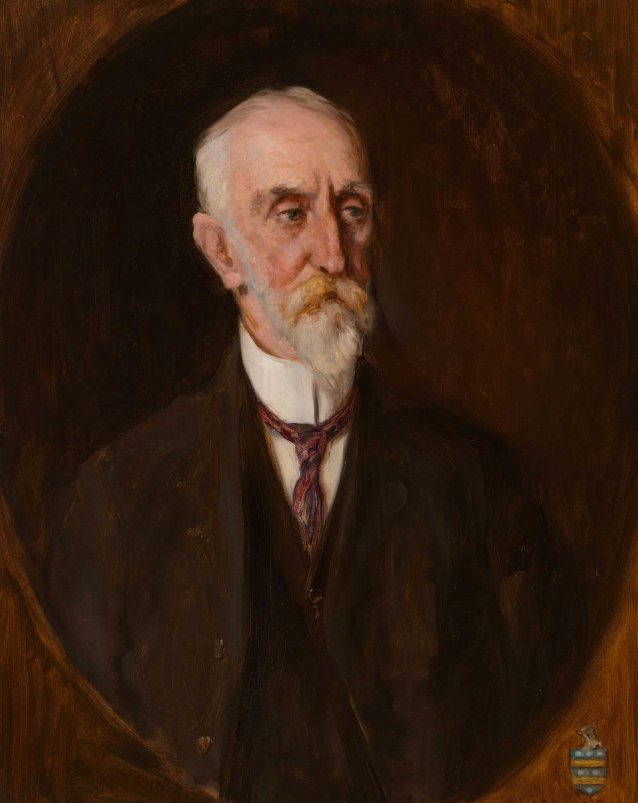

Male sitters were usually managed with the use of conventions most appropriate to a smoking room, a boardroom or a library. Her painting of her friend Eccleston Du Faur, for instance, uses an unadventurous palette and the dignified, traditional bust format befitting an arts patron and the inaugural president of Trustees of the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Teague made the work in 1911 in the hope that the gallery would acquire it, but Du Faur is said to have felt that the portrait portrayed him ‘as he would like his children to remember him’ and, aptly enough, it passed to his daughter Freda (a trailblazing mountaineer) on his death in 1915. Teague’s portrait of former Goldfields Commissioner Robert Rede, a family friend, is similarly restrained in tone and cautious in pose and execution. It received an honourable mention when it was exhibited at the New Salon in Paris in 1898, and when it was shown at the Victorian Artists’ Society in 1900 it was lauded for being ‘well-balanced and characterized by good taste’. ‘The colouring is truthful and harmonious, the pose of the seated figure easy and natural, and the whole picture dominated by a strength and reserve which are at once pleasing and distinguished,’ read the review in Table Talk. ‘It is a man’s portrait painted in a manly, dignified fashion, and in all its features is deserving of the highest praise.’

Yet she seems to have reserved her real verve for her depictions of women, particularly those who, like Teague herself, declined to see their social class as incompatible with progressivism, or their gender as intractably determining a domestic, largely decorative life. Lecturing on the subject of ‘Woman in Art’ in the early 20th century, Teague stated that ‘I began my researches in the belief that woman had done her best work in art when she sat for Gainsborough or for the exquisite Madonnas of Botticelli and Fra Angelico … [but] I find she has a great deal of fine and remarkable work done off her own bat’. Teague shared with contemporaries such as the American portraitist Cecilia Beaux an ability to infuse a traditional, supposedly outdated artform with the energy and spirit of the transitional times she lived in. Teague considered Beaux ‘the first of the modern women portrait painters’, one ‘whose work shows rare distinction and subtle grasp of character’. Just as turn-of-the-century feminism and the New Woman coexisted with limited political enfranchisement and hidebound ideas about women’s rightful roles and ‘place’, the tradition of grand portraiture persisted alongside modern modes of seeing and being seen, borrowing from sources such as fashion photography and fusing the splendour and hauteur of artists like Reynolds, Gainsborough and Velázquez with the formal ease and fluid brushwork of Whistler and Sargent.

1 Margaret Alice , 1900. Art Gallery of New South Wales. Purchased 2017 with funds provided by the Australian Masterpiece Fund, including the following major donors: Barbara Gole (in memory of), Antoinette Albert, Anita & Luca Belgiorno-Nettis am, Andrew Cameron am & Cathy Cameron, Krystyna Campbell-Pretty & the late Harold Campbell-Pretty, Rowena Danziger am & Ken Coles am, Kiera Grant, Alexandra Joel & Philip Mason, Carole Lamerton & John Courtney, Alf Moufarrige ao, Elizabeth Ramsden, Susan Rothwell, Denis Savill, Penelope Seidler am, Denyse Spice, Georgie Taylor, Max & Nola Tegel, Ruth Vincent. Image © Art Gallery of New South Wales. 2 Dian dreams (Una Falkiner), 1909. Art Gallery of New South Wales. Gift of the sitter's daughter, Lawre Bruce Steer 1975. Image © Art Gallery of New South Wales. Both Violet Teague.

‘One can see that she is a thoughtful, modern woman whose acquaintance would certainly be interesting,’ reads one description of Teague’s (now lost) portrait of fellow Atelier Blanc-Garin graduate Marie Heijermans, which was exhibited at the Victorian Artists’ Society in 1896 and reportedly had been awarded an honourable mention at the Paris Salon earlier that year. The same assessment noted certain other daring elements of the portrait: the ‘downcast eyes’, or the way that the inky black velvet of the sitter’s dress ‘contrasts with the dead whiteness of the neck and arms’, for example. ‘Not a bone in the neck is hidden or softened and no ungraceful line in the somewhat angular form,’ it continued, ‘but the figure is instinct with life and individuality.’ Margaret Alice Bartrop, the subject of one of Teague’s earliest Salon-style, full-length portraits, looks straight at you, tall, slender, glowing, physical – and supremely unapologetic. ‘The scheme of colour employed is harmonious and refined,’ said one review, ‘and the drawing is throughout suggestive of the living figure, which is not always the case in portraiture.’ In 1901, when she exhibited six works in the Victorian Artists’ Society show, it was asserted that ‘Miss Violet Teague’s portraits come as a revelation’, with her full-length portrait of stepmother Sybella, exhibited as Portrait of a Lady in Black, considered the best of them. ‘In this picture she employs hardly any colour save black, but many hues of black. This work has been well conceived as a whole, and no glaring patches of colour mar its harmonious completeness.’

Almost a decade later, when she held an exhibition of her portraits at the Guild Hall on Swanston Street, critics again noted Teague’s ‘unusual sense of colour and a certain vivaciousness of subtlety in her manner of expression’. The show included Dian Dreams, a portrait of Teague’s Melbourne art school acquaintance Una Falkiner; and her painting of the remarkable Mary Chomley, a member of the organising committee for the landmark 1907 First Australian Exhibition of Women’s Work (in which Teague exhibited). Described in 1908 as ‘tall and elegant, and … the most intelligent and highly cultured of all Melbourne’s society belles’, Chomley later distinguished herself when serving as superintendent of the Prisoners of War Department of the Australian Red Cross in London, in which role she coordinated a team of volunteers to distribute thousands of parcels containing food, blankets, clothing and ‘comforts’ to Australian troops taken prisoner on the Western Front. Arresting and confidently executed, the portrait of Chomley is Teague in top form, effortlessly balancing the legendary drive and efficiency of its subject – who was nicknamed ‘The Grenadier’ – with her status as one of Edwardian Melbourne’s pre-eminent ladies. The portrait of Falkiner, similarly ‘boldly and directly painted’, is also deceptive: what seems at first glance to be merely a sophisticated study of a sophisticated woman was in fact a work which blithely ignored expectations of portraiture in showing its subject so serenely oblivious to the viewer’s gaze and so at ease in her own, beautifully rendered skin. Dian Dreams won a bronze medal when it was shown in the Panama Pacific Exhibition in San Francisco in 1915.

But ideas had changed by 1921. In much the same way as artists like Sargent suffered from an inability on the part of some to see beyond the status or symbolism of their sitters – Sargent’s portrait of Henry James, for example, was famously taken to by a suffragette with a meat cleaver when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1914 – Australian critics started to see Teague’s portraits as a throwback, style-wise and subject-wise, and out of step with an art establishment that sought to lionise artists whose work spoke to unchallenged myths about national identity. Reviewing Teague’s 1921 show, the boorish Bulletin – which preferred its men men, its women in the kitchen, and its art a hymn to the bush and the land – described her work as ‘often marred by faults of colour and drawing’ and dismissed her sitters as ‘female virtuosos curving over pianos, insipid Sassiety ladies in dowdy raiment, and a towering dowager with the tail of a bygone skirt posed in the foreground’. The altarpiece The Adoration of the Shepherds was the only work the review had any time for. The Age, meanwhile, stated that Teague’s exhibition ‘strikes the note of the period in British art that filled so many homes with life-sized portraits’ and then paid a backhanded compliment: ‘Paintings on this scale pitilessly reveal every weakness from which the work of an artist may suffer, so that it is a tribute to Miss Teague that an exhibition containing so many large canvases gives a generally good impression.’

One gets the distinct feeling, however, that Violet Teague wouldn’t have given a fig for what anyone else thought and, as scholars such as Juliette Peers have pointed out, to blame her former absence from histories of Australian art on gender or subject matter is ‘too obvious and too simple [for] an artist of such plurality and complexity’. In addition to portraits, landscapes, genre pictures and altarpieces, Teague was an innovative early Australian exponent of Japanese-style woodblock prints, producing a book of them – Nightfall in the ti-tree – with her friend Geraldine Rede in 1906 and delivering lectures on the technique for the Victorian Arts and Crafts Society. During the First World War, she initiated a series of tableaux vivants of scenes from Australian and British history, which were presented to raise funds for civilian charities. In 1932 she travelled in Central Australia, including to the Hermannsburg Mission, and was so shocked by the conditions in which the Arrernte people lived that she organised an exhibition in Melbourne to raise funds to pay for a permanent water supply for the Hermannsburg community. Insipid? Like hell. Consistent in her own pursuit of creative and personal independence – irrespective of stylistic trends and societal expectations – it’s unsurprising that Teague’s best portraits deftly combine tradition and modernity, portraying sophisticated, educated and independent women in such a way as to hide her originality and non-conformity in plain sight. ‘Some painters choose art for their career and start off in a tempest of ambition and conceit, and think to wrest success by violence and industry,’ Teague said in 1925. ‘Some listen quietly to the still small voice and, living close to nature, find what the others miss.’

![Portrait [Sybella Teague], 1901

Violet Teague Portrait [Sybella Teague], 1901

Violet Teague](/files/8/0/0/7/i16618-th.jpg)

![The staff, Prisoner of War Section, Australian Red Cross, London [Mary Chomley in centre], between 1915 and 1918 Walshams (photographer) The staff, Prisoner of War Section, Australian Red Cross, London [Mary Chomley in centre], between 1915 and 1918 Walshams (photographer)](/files/f/9/f/b/i16626-wd.jpg)