“Doing the flowers” can be a joy, but don’t embark on too ambitious an arrangement if housework crowds in on you.

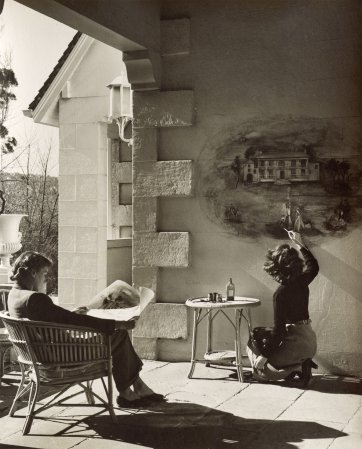

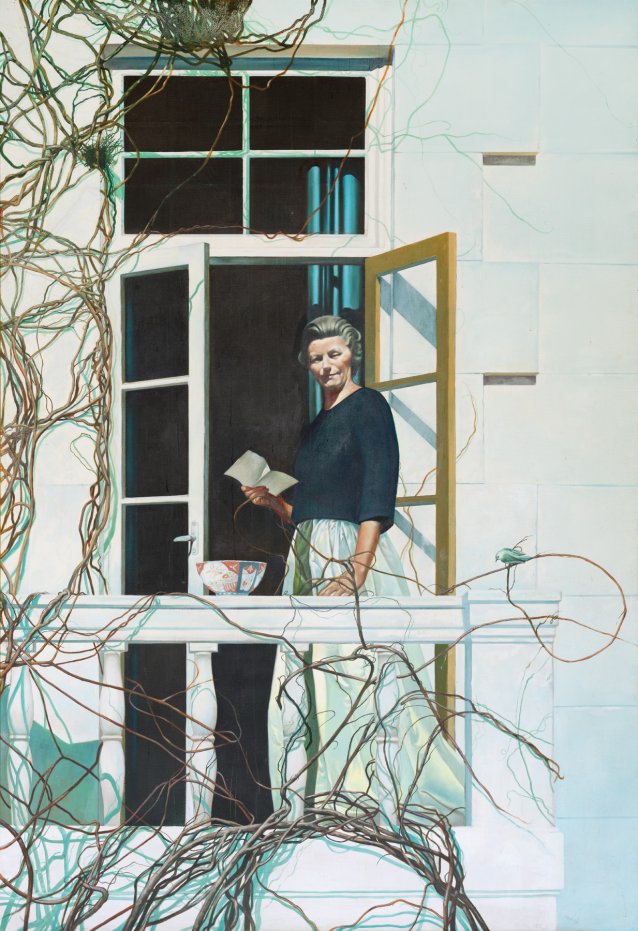

Evergreen advice on time management and keeping it real, it comes from an issue of the Women’s Weekly in the lead-up to Christmas 1965. ‘Flowers for Christmas’ was a feature from Sydney’s long-established authority on floral artistry, Helen Blaxland. Chic and strict, she was photographed for decades, typically pictured scrutinising an arrangement under a headline like ‘Good vases don’t just happen’. Yet over time, her interests were to deepen and expand, first to charity fundraising and ultimately to built-heritage conservation. By the late 1960s, while conceding still that there was no house that wasn’t improved by flowers, if entertaining, she advised, ‘ask some young girls; they are pretty and far cheaper!’

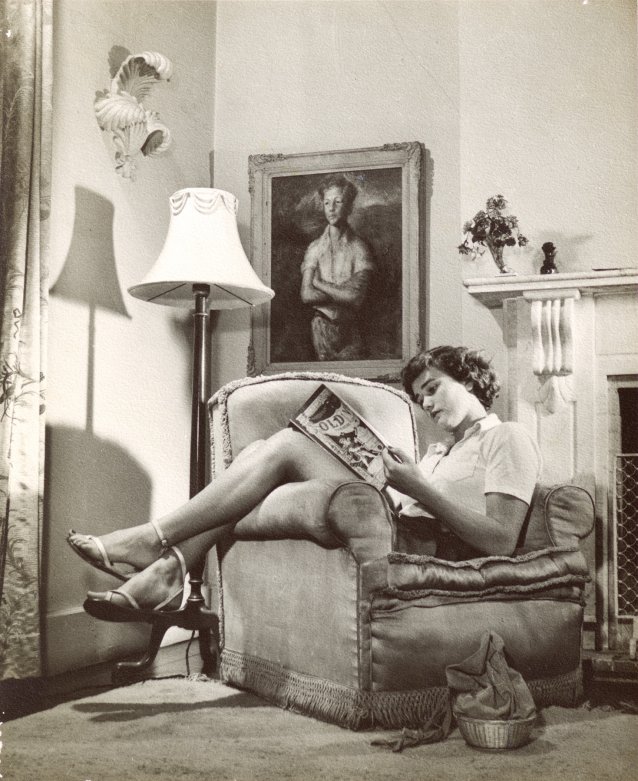

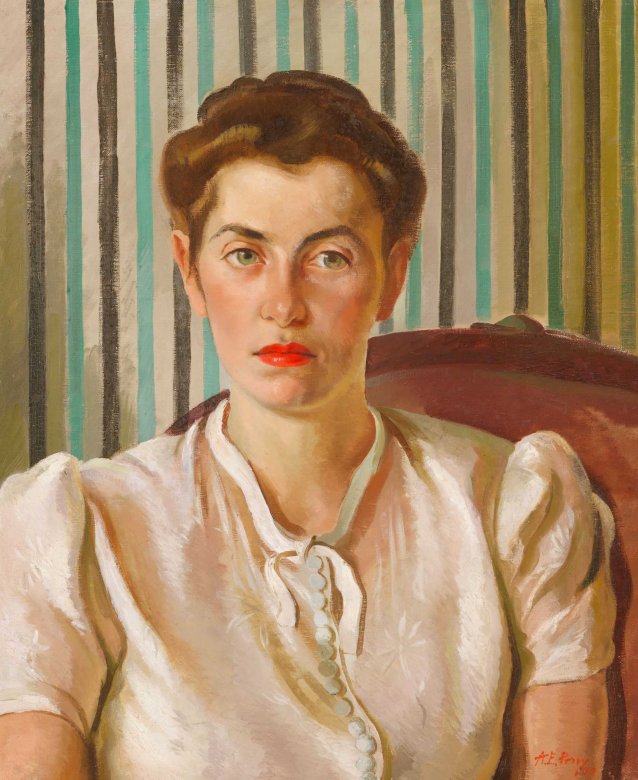

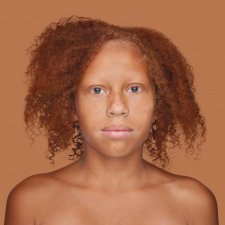

Born Helen Anderson in Sydney, the woman who evolved into Dame Helen Blaxland was educated at Bedales, Hampshire then at Frensham, Mittagong before taking art classes at Julian Ashton’s, Sydney. Her parents were a potent pair. Her father was Brigadier General Sir Robert McCheyne Anderson KCMG, and her mother, born Jean Amos, graduated in Arts from Sydney University just five years after the first women to do so. Helen married at twenty and was henceforth styled Mrs Gregory Blaxland. Though a mother by 22, she continued to eclipse such Younger Set peers as Miss Nuttie Mackellar and Ginette Scamps. She was a snappy dresser. Pre and post-war, her recorded outfits and accessories included an ensemble of lizard green wool crepe banded with opossum fur; an alpaca getup with a pale pink turban twisted round a cluster of pink roses; and a wide leopard muff that matched her tiny cloche. Along with that, she was tall and forthright. Even the way she moved was approved. At 27 she starred in a news feature on ‘Sydney Women Who Walk Well’ – ‘her freely swinging and courageous type of walk makes her the cynosure of many envious eyes on the golf links and beaches.’

Helen’s spouse, Gregory Hamilton Blaxland, was an engineer conscious of his antecedents. His mother was a Downer from Adelaide and his great-grandfather was Gregory Blaxland, one of the first white men to see country west of the Blue Mountains. Amongst family papers at Camden Park is a Blaxland family tree running back to the era of William the Conqueror. Sydney’s very corners whispered of young Blaxland’s pedigree. The elder explorer Gregory Blaxland’s brother, John, lived for a time at the intersection of Market and George Streets Sydney, and that’s how the Blaxland Galleries in Farmers Department Store got their name in 1929. John Blaxland proceeded to build a fine home, Newington, on the Parramatta River. After his trip with Lawson and Wentworth, Gregory Blaxland grew grapes at his property, Brush Farm on the Field of Mars, becoming the first man to export wine from Australia. The young Blaxlands proclaimed the connection by transferring the funny name to the house in which they lived in Woollahra from the 1940s to the early 1970s: Brush.

The histories of the Blaxland brothers’ houses echo those of quite a few big-ticket Australian colonial homes, with which few have ever known quite what to do, and for which few have ever really wanted full responsibility for long. Brush Farm became the Carpentarian Reformatory for Boys in 1894. Within 50 years it was a school for feeble-minded and other female wards of the state aged four to fourteen years. Purchased by the Department of Corrective Services in the late 1980s, it was soon sold to Ryde Council, but still houses a training centre for corrective services officers, with spaces available for party hire. Similarly, up to 1968 John Blaxland’s Newington saw use as a reformatory school; a hospital and an old women’s asylum; was threatened with demolition; then transferred to what was then the NSW Department of Prisons. Now accommodating office staff, it stands in a designated Conservation Area in the grounds of the Silverwater Correctional Complex.