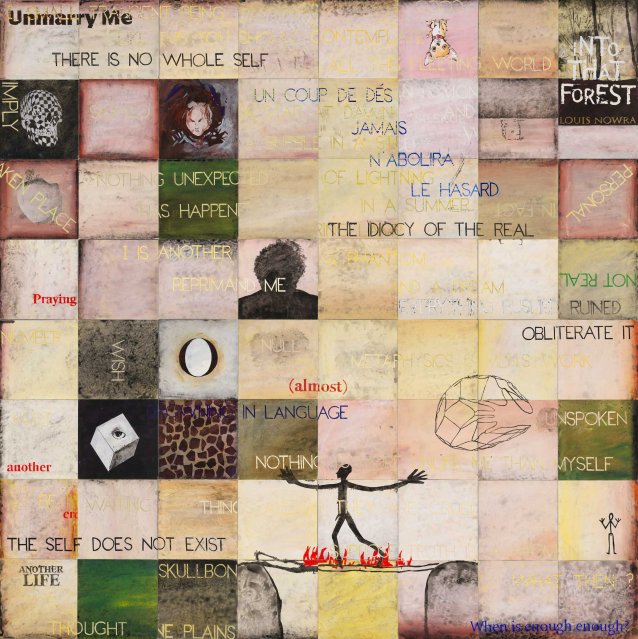

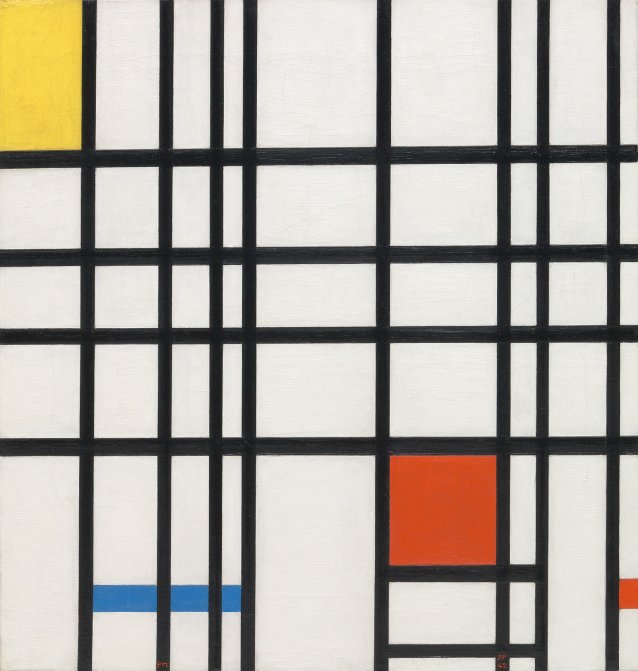

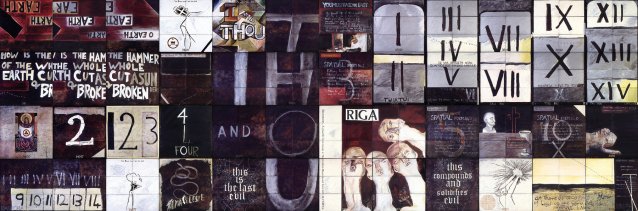

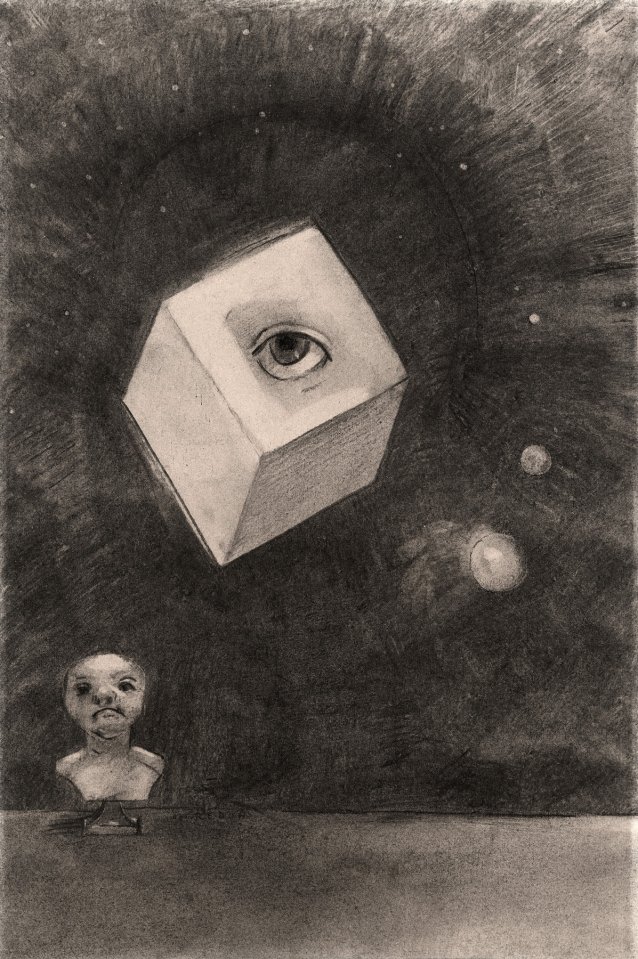

Exploring the idea of the grid within Nowra’s portrait, ‘beyond’ the sequence of square panels, we see a cube with eye peering out at the viewer – a motif from Odilon Redon’s charcoal drawing, Le cube (1880) – along with a human skull with grid stretched over it, inspired by an image from Mexican contemporary artist Gabriel Orozco that the artist liked for its peculiar nature. The inclusion of these mysterious motifs may be read both as existential signs for personal reflection and providing context for Nowra’s life experiences. The motifs, then, are elements ‘beyond’ both the subject and frame. Similarly, Nowra’s storytelling includes characters displaying the writer’s traits, in tales based on the anomalous events in his life. As Tillers notes ‘truth is actually stranger than fiction. And Louis’ autobiography ... you couldn’t actually invent a fiction like that and yet that’s what happened to him.’

It was a troubled childhood, to put it mildly. In his 1999 memoir, The Twelfth of Never, Nowra relates unimaginable stories. In one, a young Louis watches on as his granny jabs at a bonfire with a rake, ‘her eyes mesmerised by the rainbow showers of sparks and flames … Everything that had been in my suitcase was on fire, as were some of her nylon and rayon clothes that were shrivelling and melting in the heat.’ In his portrait we see a possible reference to the tale, with a stick figure Nowra, arms outstretched, traversing a flame-lit wire.

Tillers explains ‘after meeting Louis and reading several of his books, my suspicions were confirmed and I realised that he truly was fearless in his life and work, and this is what I wanted, above all, to portray’. The figure’s form came about via a discussion between Tillers and Nowra and their mutual friend and author, Murray Bail, who asked Nowra how Tillers should paint him. ‘He’s painting me as a stick figure’ came the quipped response. Taking this on board, Tillers included a stick figure without its facial features. Nowra had earlier commented to Tillers that he was not a fan of the formal portrait, suggesting that he could paint the back view of him.

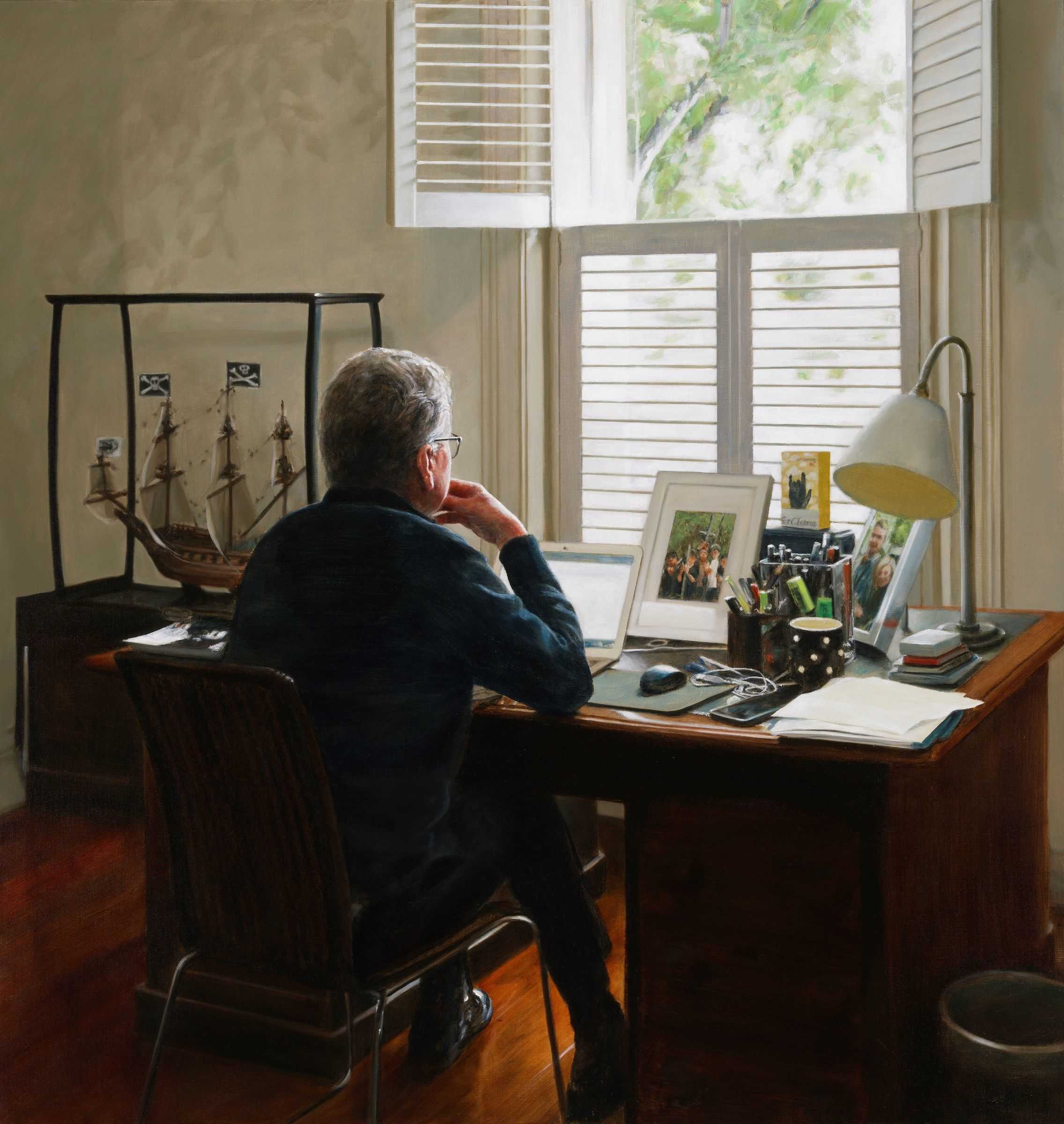

Tillers notes, ‘there is also a literal image of Louis in the painting which is kind of a back view… there’s a bit of chance in my work and when I painted the silhouette of him, it looked like a view of him from behind.’ The resultant portrait, as Louis and his wife Mandy Sayers said to Tillers, is ‘a mental picture rather than a literal one’, consistent with the concept of portraiture beyond the frame.

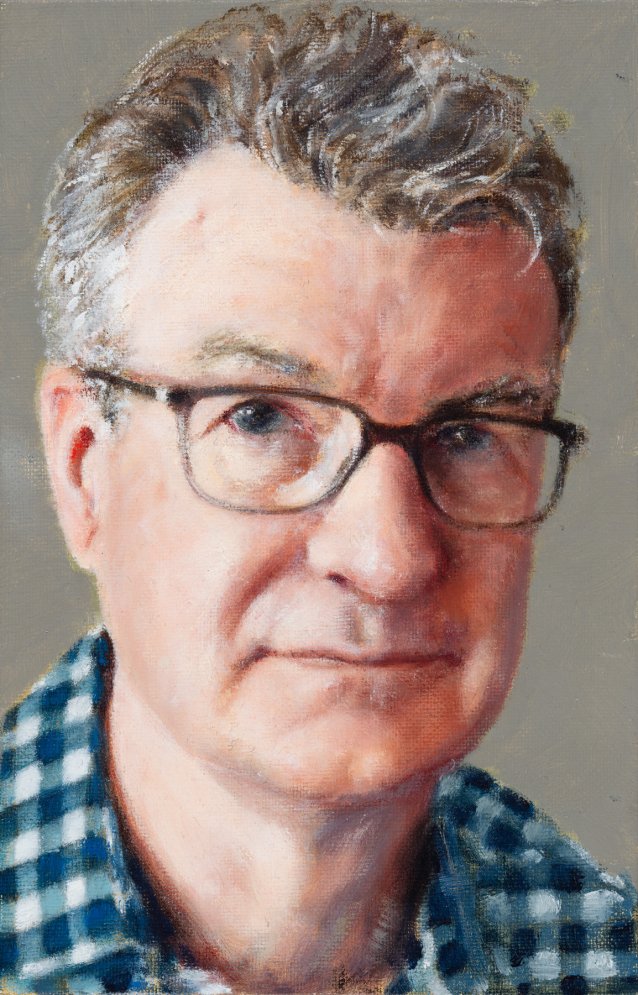

As portraits that communicate both within and beyond their frames, these two new works by Deidre But-Husaim and Imants Tillers add to the Gallery’s growing number of non-representational portraits. The paintings communicate more than the subject’s features; they explore aspects of their identities, inviting observers to engage in a more involved and nuanced way, revealing inner truths for both artist and viewer alike.