What’s your preference: flagrantly theatrical portraits, in which the subject appears to be playing opposite the artist in a drama they’ve devised together; or portraits in which we forget the involvement of the artist, for the subject seems to appear as pure self, every mask of convention and conformity dropped, all artifice fallen away?

Amongst the twenty portraits commissioned to mark the twentieth anniversary of the establishment of the National Portrait Gallery, nine photographs fall at both poles, and along the axis between.

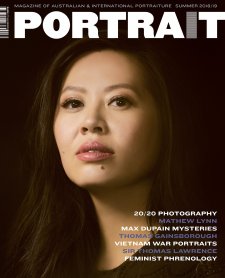

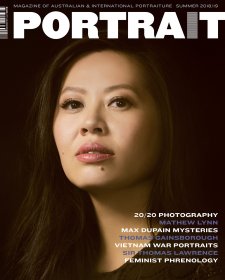

From the actor Jacki Weaver – renowned locally for effervescence before taking on dark roles that won her exceptional success in her sixties – John Tsiavis has coaxed a face from mythology. She’s a fury, a sorceress, a seer; a woman who will be avenged; a mother defending her young. She’s Bellona, Boudica, Medea, Scáthach. Weaver’s nasolabial folds – the lines from nose corners to mouth corners – are pronounced. Commonly they’re called laugh lines, but there’s no hint of humour here. This is a woman who’s had it with being called cute.

But Weaver’s expression is staged. She’s putting it on; we know it, and we’re supposed to know it. The makeup on her face is plain to see: the foundation and concealer around her eyes and on the bridge of her nose; her eyeliner; her false eyelashes; her contour medium; her eyebrow pencil; her powder. She looks defensive as well as fierce; but the garment she draws in close is an ordinary coat, not a cloak. She’s not on a battlefield, at the entrance to the castle keep; she hasn’t swooped in like a Harpy or appeared on the rocks like the angriest of the Valkyries. Her hair’s being blown by a carefully-trained fan. Her look belongs to a woman who’s wild, but her one visible nail is manicured. Weaver appears to possess the unusual talent of being able to lift her right eyebrow (it’s said this is a skill that can be learned, and it’s surely a good thing to know how to do). I’d guess more actors are able to do this than, say, curators, accountants or plasterers.