Nonetheless, Rick Smolan’s photographs remain a greatly cherished visual record of Davidson’s expedition, due to their inherent beauty and timeless charm. Smolan illustrated the intense beauty of the Australian landscape, as well as Davidson’s quiet determination in the face of an almost surreal isolation. They are sensitive, intimate portraits that depict Davidson within the landscape, while poignantly and often humorously capturing the unyielding love and respect she had for her animals.

While these striking photographs taken at the time of the journey are the closest thing to the visual ‘truth’ of Davidson’s experience, they remain a subjective rendering – a projection. A range of variables contribute to the story that Smolan’s photographs tell: he was an American photographer working in an unfamiliar, exotic landscape; he shot with an inherent ‘male gaze’; he was only present for a short few legs of the journey, such that his images only capture fragmented moments of the whole; and, finally, his photographs were commissioned for a publication, so their scope was informed by the expectations of the magazine’s audience.

In her 1980 memoir, Tracks, Davidson alludes to Smolan’s intrinsic perspective, noting, ‘They were gorgeous photos, no complaints there, but who was that Vogue model tripping romantically along roads with a bunch of camels behind her, hair lifted delicately by sylvan breezes and turned into a golden halo by the back-lighting. Who the hell was she? Never let it be said that a camera does not lie. It lies like a pig in mud. It captures the projections of whoever happens to be using it, never the truth.’

What then of the ‘fictional’ representation? Matt Nettheim is a prolific Australian stills photographer who has worked locally and internationally on films including The Babadook (2014), Hot Fuzz (2007) and The Eye of the Storm (2011).

His oeuvre also demonstrates a deep-rooted familiarity and comfort in capturing people within the landscape. This is particularly evident in his work from Rabbit Proof Fence (2002), Oyster Farmer (2004) and The Tracker (2002). His sensitive portraits of Mia Wasikowska in the role of Robyn Davidson in Tracks (2013) play homage to the photographs of Smolan, through their verisimilitude in composition and tone. In an interview with National Portrait Gallery Assistant Curator Penny Grist, Nettheim spoke about his experience on the set of Tracks commenting that he enjoyed working on a film where photography played such a pivotal role in the story. ‘Tracks justified me getting my film camera out again because it’s about a photographer … Every now and then the lead actor Adam Driver would consult me on how to hold the camera or something about photography.’

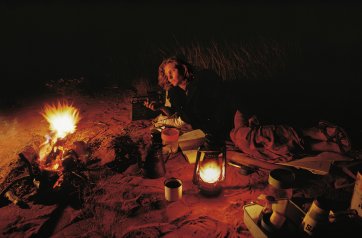

Interesting parallels can be drawn between the role of an on-set stills photographer and that of a photojournalist. On-set photographers like Nettheim work to stealthily pursue all opportunities for a shot, regardless of the time and space available for them to do so. Nettheim notes of his experience in this field, ‘You are standing around for hours, then you have a few seconds to get your shots and you are almost irrelevant; you are in the way and more of an irritation’. In a similar vein, photojournalist Smolan faced the challenge of capturing both the good and bad experiences of Davidson’s Journey. Davidson recalls an emotional moment in which she farewelled her friend Jenny: ‘I felt like pummelled dough and Rick took photos of us. We despised him for it – saw it as a form of parasitism, voyeurism.’ It was through this almost invasive documentation that Smolan was able to capture intensely intimate portraits of Davidson, whether comforting her camels, or relaxing at camp, visible only by the fireside glow illuminating her face.

When creating Tracks in 2013, John Curran (Director), Mandy Walker (Director of Photography), Melinda Doring (Production Designer) and Mariot Kerr (Costume Designer) were grateful for Smolan’s images. His photographs were important reference points for re-creating the character likeness of Robyn Davidson through makeup, costuming and production design. The likeness in costuming is clear when comparing the images of Robyn and Mia at Hamelin Bay, as well as the tousled hair, check shirt and red-brown wrap skirt, which feature both throughout the film and in many of Smolan’s photographs. Images of the landscape and key locations were also vital in creating a cinematic portrait of the Australian outback. John Curran recalls that he wanted to make a film ‘where the landscape itself was a character’. The capacity to refer to the landscape in Smolan’s images was central to achieving this.

While there was a desire on the part of the filmmakers to match the look and feel of the original photographs by Smolan, both Curran and Davidson were acutely aware that the contemporary landscape told a very different story to that of 1977. In 2012, Davidson remarked on the Australian desert and the native animals she had admired during her journey: ‘Many of those animals are rare and gone. Their tracks are replaced by camel pads … and fox prints and rabbit holes’. Davidson has written further on this concern more recently, suggesting, ‘The desert belongs to another “now” and it is foolish to compare them. Just as it is foolish to compare the “truthfulness” of the book Tracks, Rick’s pictures of the journey, and the film. Each had its own artistic integrity; each is in dialogue with the others in the realm of imagination.’ Davidson was supportive of Curran’s approach to the film and was consulted at various stages of production. And the intent behind the film was clear: to tell a new story about Robyn Davidson’s experience, in a new era, through a new medium, and to a new audience.

The photographs taken by Matt Nettheim on the set of Tracks also tell another story. They not only re-imagine Robyn’s story, with actor Mia Wasikowska as the subject; they also document the nature of storytelling and the filmmaking process. The origins of stills photography in cinema stem from the production of publicity images for the marketing of a film. Nettheim’s work pays tribute to Smolan’s images by appropriating familiar visual clues and composition. Despite their apparent similarities, these new photographs are not simply an exercise in mimicry; rather, Nettheim creates new, captivating images for the promotion of the film. This similitude works to engage audiences who are already familiar with Davidson’s story and Smolan’s images, while simultaneously presenting fresh, intriguing pictures which, in isolation, are able to effectively engage the viewer and captivate a new audience for the film.

The photographs of Robyn Davidson and Mia Wasikowska, taken by Rick Smolan and Matt Nettheim respectively, represent their own reality – whether in an attempt to document Davidson’s adventure or her relationship with her animals and the Australian landscape – or whether it was to capture the reality of filmmaking and Curran’s fictional representation of a familiar story. In the same way that these images capture a form of reality, they are also constructed images, produced to serve a purpose and appeal to a particular audience, be it magazine subscribers or filmgoers. Either way, they are intriguing photographs that are of their time and place, and celebrate the experiences of a young woman and her very personal journey.

This article has been written as part of a major collaboration between the National Portrait Gallery and the National Film and Sound Archive, supported by the National Collecting Institutions Touring and Outreach Program.