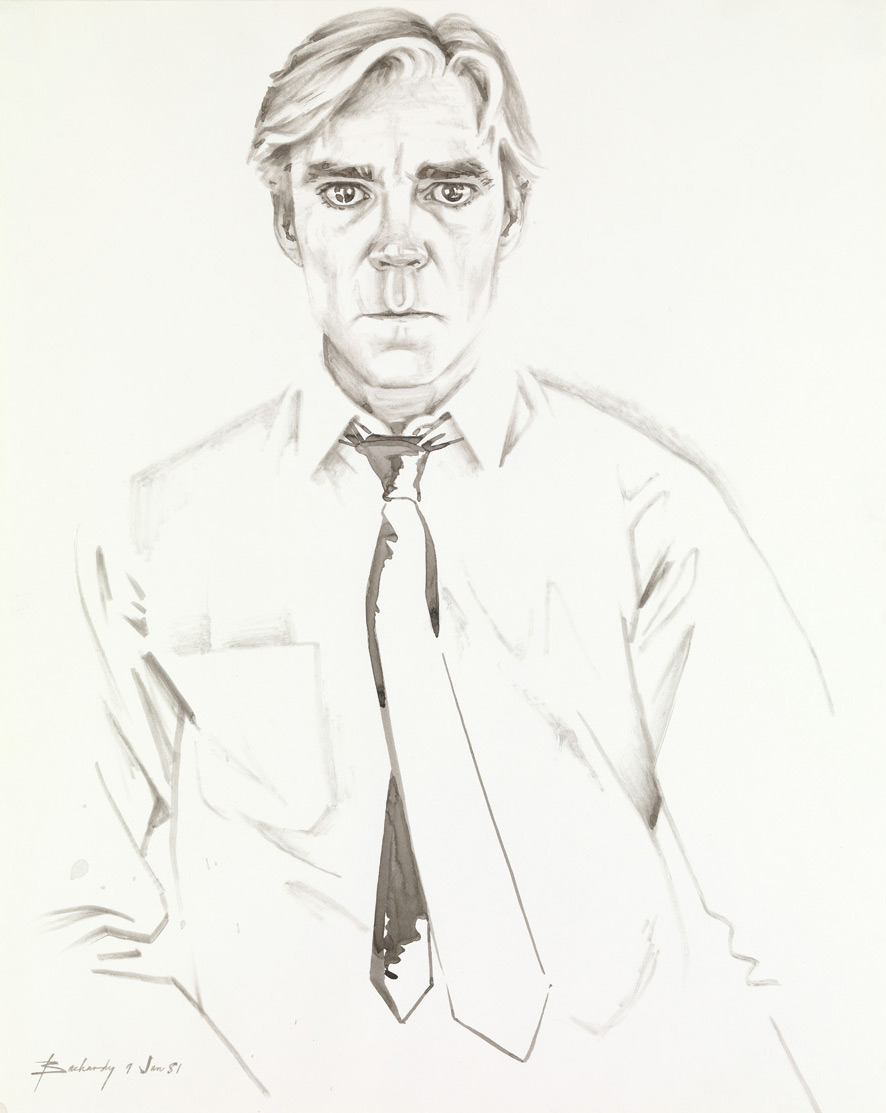

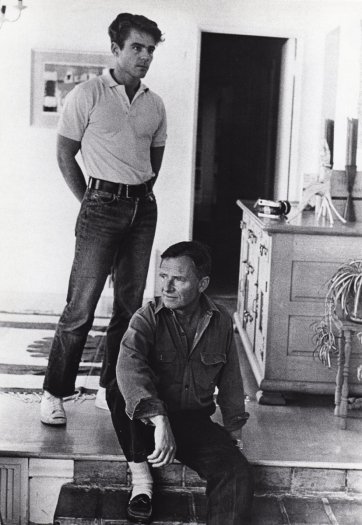

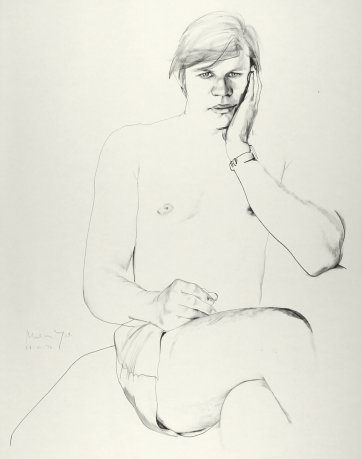

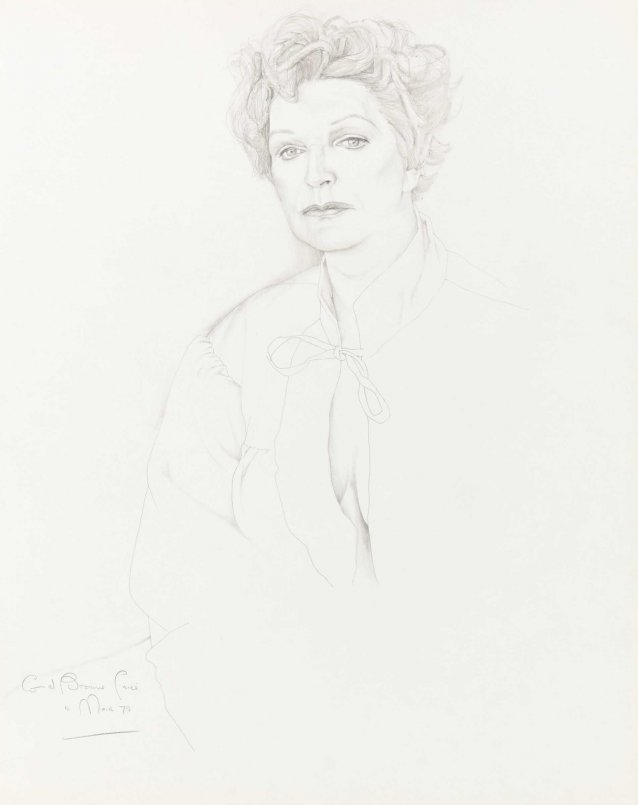

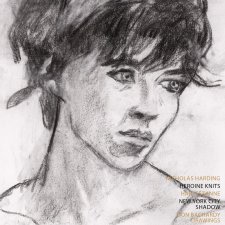

Bachardy’s late 1960s portrait drawing of British-American poet Thom Gunn, held by London’s National Portrait Gallery, shows Gunn aged in his late thirties, all angular features and luxurious hair. Gunn seems to be contemplating his own self; he seems to be thinking, ‘how is it that I am this person now?’ Gunn would eventually use his poetry to reflect on the emotional stakes of physical contact and connection between men, and to echo the elegies for gay men who died from AIDS during the virus’ 1980s peak. His early poems translated his specifically homosexual psychological understanding into universally accessible themes. Moving to America in 1954 to be with his US Air Force officer partner Mike Kitay, Gunn used the word ‘you’ instead of ‘he’ in his love poems. He guarded his homosexuality. Had he come out then, Gunn told interviewer James Campbell, he ‘would never have got to America’, ‘would never have got a teaching job’.

I had almost reached the circumstance where my own coming out took place, when a good friend gave me a worn ex-library copy of Gunn’s slim volume of poems, My Sad Captains, of 1961. ‘They were men who, I thought, lived only to renew the wasteful force they spent with each hot convulsion’, the title poem’s central lines whisper. Jay Parini wrote that the poem was Gunn’s ‘farewell to the past’. It was ‘a tender yet fiercely self-critical piece’, says Parini, ‘a resolution to approach life and art from now on with greater flexibility and humaneness’.

Since adolescence, affection conditioned my connection with close male friends. Allegiance was based on what I would now call ‘intellectual intimacy’ (through which I was invited to share in knowledge of certain record labels, for example). Throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s I yearned to be able to love my ‘best friends’, to hold them close. All the while, I maintained the necessary protections that had been a survival method since childhood. My true self was camouflaged. When he gave me Gunn’s book of poems 30 years after they were first published, did my friend know that Gunn was gay? Why then would our friendship evaporate when I came out to him? Had the closeness of our friendship, its emotional intimacy, suddenly appeared as ulterior or disingenuous? Time and place, the attitudes of family and friends, the real or perceived risks to personal wellbeing always influence coming out. In my twenties, I battled with myself. I, too, distanced myself from gay friends because of my own fear of association. The thrill of coming out was followed by years of sublimated resentment. I blamed society for denying me language to guide the discovery of my real self, an ‘insult’ that, as Didier Eribon puts it, ‘lets me know that I am not like others, not normal’. (Eribon also calls upon philosopher Michel Foucault’s 1976 reflections on his self-discovery as homosexual: ‘for those from earlier generations,’ Foucault says, ‘it was a kind of magic, the day you realised that that is what pleasure was, and at the same time there was the feeling that you were marked, the black sheep’.)

Aged in his seventies, Thom Gunn pointed out to interviewer Christopher Hennessey ‘do I think self-discovery or self-knowledge is an important part of my work? Yes.’ Poetry, Gunn said, invoking the words of his ‘old teacher’ Yvor Winters, ‘is an attempt to understand – not that one can succeed in understanding, but the attempt to understand’. Gunn told Hennessey his poem ‘The Allegory of the Wolf Boy’ (written when Gunn was 26 or 27 and published in 1957) can be understood as representing the first stage of coming out. The poem was inspired by a story he had read at age 14 (by Hector Hugh Munroe, who used the pen name ‘Saki’) about a ‘werewolf who was a boy’. Clive Wilmer, in his notes to Gunn’s Collected Poems, says Gunn ‘confirmed in conversation that the poem was about growing up as a gay youth and feeling compelled to live a double life’. For Gunn, the poem ‘struck me as a marvellous allegory of sexuality – all sexuality – being covered over by clothes,’ he told Hennessey, ‘and desire, the wolf, coming over the person who is very reluctant to acknowledge but can’t help acknowledging it’. The poem’s last stanza reads:

‘White in the beam he stops, faces it square.

And the same instant leaping from the ground

Feels the familiar itch of close dark hair;

Then, clean exception to the natural laws,

Only to instinct and the moon being bound,

Drops on four feet. Yet he has bleeding paws.’

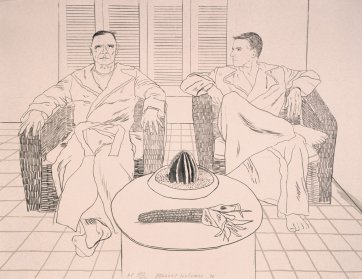

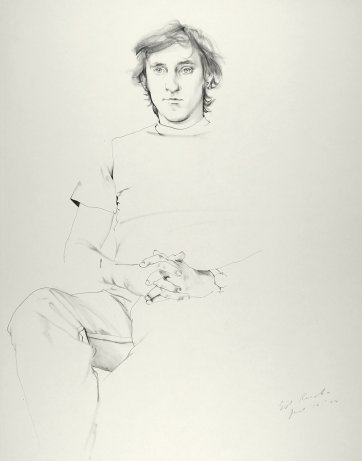

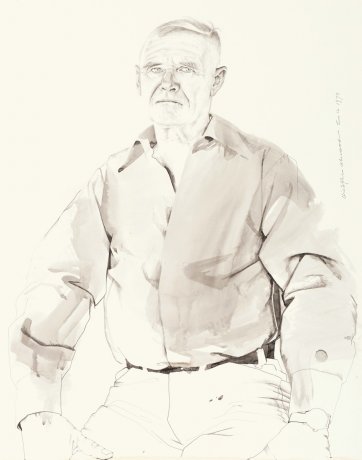

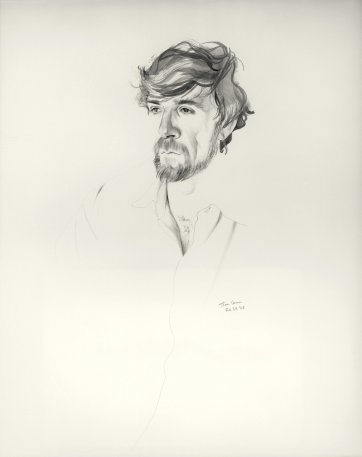

I can imagine that in his portraits of Thom Gunn, Don Bachardy is recognising someone who is like himself. He is looking with a depth of understanding, based on shared emotional and psychological experience. How is this apparent in the drawings themselves?

The deftness, the lightness of style that Bachardy brings to his portrait drawings is how he sees his subjects, how he translates their physicality and psyche for us. A complex multitude of interests, experiences and artistic exploration informs Bachardy’s artistic style. This is what characterises his work, as every artist’s own pursuit of ‘understanding’ characterises their own.