Immersed and atomised selfhood seems to be a natural state of being in today's technologised world. We have rapidly acclimatised to the ubiquitous forms of communication that require continuous interconnection and immersion. Using the telephone once meant you had to be at home, at work or in an operational payphone, physically anchored to a place in time and space. Now, talking-while-moving, texting, sending pictures and emails is the natural state of communication. Your body might be physically here, your mind is simultaneously there. The woman who was using Facebook on her mobile phone when she walked off the edge of St Kilda Pier into the water at 11.30pm in December 2013 may not have known how to swim, but surely was quickly reminded of the real world while her mind was elsewhere. It’s increasingly easy to slip into the virtual world. Two recent artistic works – Dave Eggers’s novel The Circle and Spike Jonze’s feature film her, both 2013, explore ideas of the immersion and atomisation of selfhood (Americans Jonze and Eggers happen to have collaborated on the screenplay for the fantasy world of Jonze’s 2009 film adaptation of Maurice Sendak’s 1963 children’s book Where the wild things are).

In his book The Circle Eggers describes a dystopian near-future eerily close to our own, where the omnipresence of a corporate internet giant evolves into a totalitarian force. The inevitability of the narrative unfurls with chilling logic. A corporatised update of George Orwell’s 1949 novel Nineteen Eighty-Four the government slogan war is peace freedom is slavery ignorance is strength has evolved into sharing is caring secrets are lies privacy is theft in Eggers' The Circle. In the book, the story of young woman Mae Holland’s ascent within the corporation The Circle facilitates Eggers' social critique.

The campus of The Circle is utopian and its experiences seamless. It is pervaded by logic and order so that for Mae, venturing from the purity of The Circle campus to the larger surrounds of the city is increasingly difficult. Eggers described Mae’s trepidation about leaving The Circle campus: ‘There were homeless people, and there were the attendant and assaulting smells, and there were machines that didn’t work, and floors and seats that had not been cleaned, and there was, everywhere, the chaos of an order-less world.’ However, it’s also in this outside world that Mae forgets herself when kayaking on a moonlit bay, where she is reminded of the joy of solitude and reflection. Her life at The Circle is controlled since Mae’s sense of self is constantly calibrated by a continual state of self-awareness. At The Circle Mae goes ‘transparent’, fitted with a high-definition camera that broadcasts her actions and words to millions of online followers. She is always on, her behaviour and vocalisations constantly broadcast to followers across the globe who provide ongoing instant feedback through messages and emoticons to Mae’s actions and words. Soon enough, before speaking or acting, Mae finds herself self-consciously checking the calibration of her thoughts – pre-empting their possible effects. Her quickly attained celebrity amongst her workmates and internet followers also affects her interactions with those around her – when other people are talking with Mae and interacting with her, they too are aware that they are addressing her millions of followers.

At one point, momentarily, Mae acknowledges the stress of constant connectivity, and then rationalises this state for its information-gathering and transmitting imperatives. Mae’s ambivalence about existing in a constant state of being on reflects a recent real-life study on the effects of constant surveillance. The study on the effects of surveillance in the home over a sustained period of time – the Helsinki Privacy Experiment – found that most subjects became accustomed to the situation. Ten households, mostly with solo occupants or participants, volunteered to be monitored for six months by video and audio feeds, and recording of their smartphone usage and computer key-presses and screenshots. While the study found ‘no negative effects’ on the ‘stress and mental health’ of the subjects; they knew that their data was being used for the purposes of the study (as opposed to being collected anonymously – or by the police or government). However, the study noted that the surveillance system also caused instances of concern and anxiety particularly with regard to the capture of intimate moments, nudity and sexual activity. All subjects changed their behavior in some way in order to seek privacy. The visible cameras, in particular, were a reminder of the surveillance, and they were at times covered or unplugged, the researchers stating that ‘the subjects did not describe blocking any other sensor, although all were taught how to do so.’

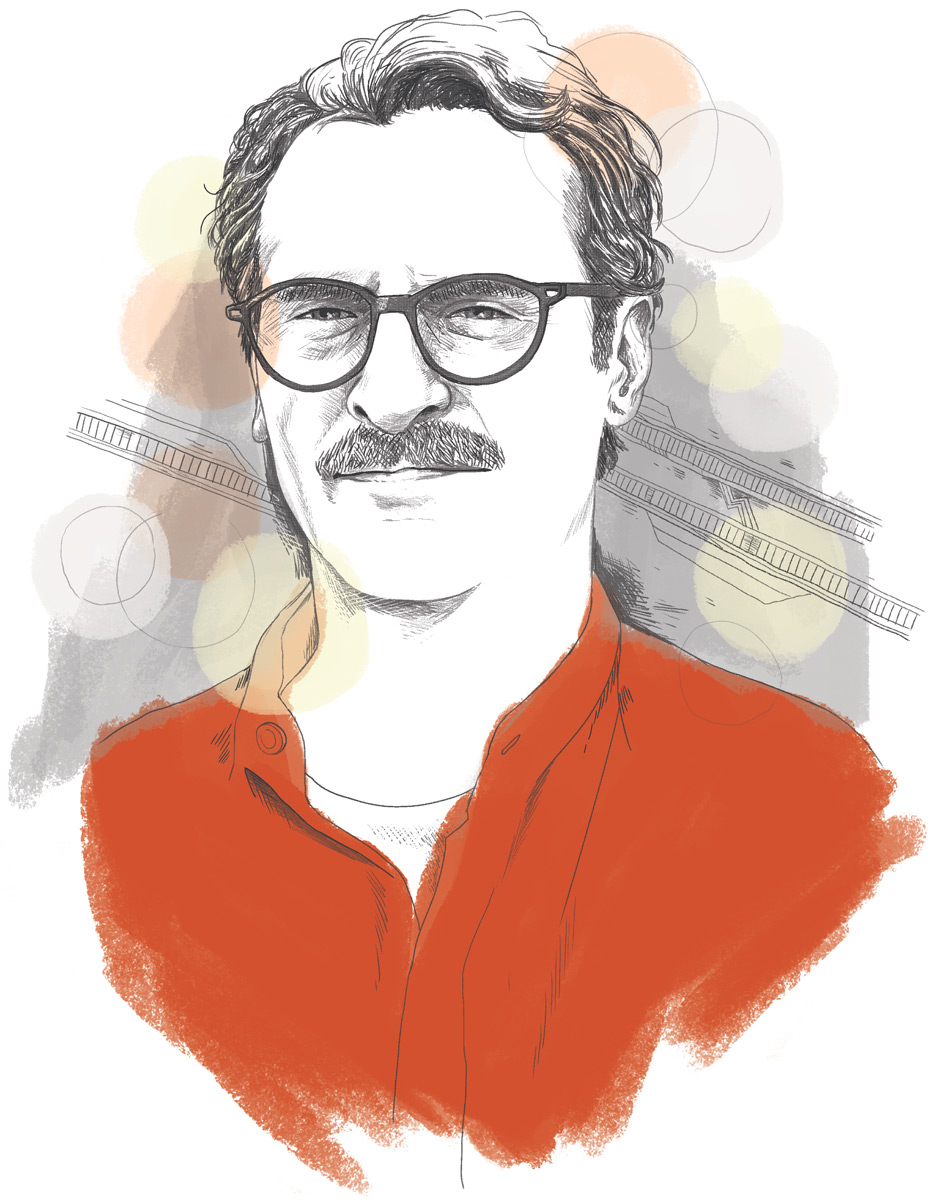

In Spike Jonze’s feature film her Theodore Twombly falls in love with his computer operating system, Samantha, voiced by Scarlett Johansson. Samantha has access to all of Theodore’s computer files and emails, and therefore knows all about Theodore – so that she can sympathise with his emotional states, and even communicate through the web on his behalf, without his knowledge. Theodore is always connected to the virtual world except for when he’s asleep. He and the human inhabitants of his world use a small earpiece (like a wireless iPod earbud) to communicate with their computer operating systems – all of them talking while walking, but not to each other, instead of interfacing through a screen (like our phones and tablets today). Theodore’s computers – at home and at work – lack keyboards, all communication is spoken.

The world of Theodore Twombly’s near-future is highly recognisable. It’s utopian too – a clean and green world – infused with pastel light. The film’s production designer KK Barrett described its cityscape setting as ‘curvaceous’, a seamless collage of high-rises extant in Los Angeles and in Shanghai’s commercial Pudong district. Theodore’s apartment, high in a residential block, overlooks the city. Its big windows and sparsely-furnished open space capture Barrett’s intention to give ‘the illusion he was floating’, a reflection of Theodore’s un-anchored sense of selfhood as he gently moves through the city and through this episode in his life.

Samantha’s selfhood is necessarily atomised. She exists purely as computer code, dispersed across servers and in the cloud, constantly interfacing, constantly integrating information, analysing data, and interpreting it for others and for herself. Samantha’s dilemma is existential: how can she account for her own existence – one that is so newly described? She yearns to experience the physical sensations generated by having a flesh-and-blood body, and on occasion feels resentment for this lack in her own selfhood. Her perception is characterised by cognition and a sophisticated ability to learn what it would be like to have human feelings and emotions, and she also describes the existence of a form of somatic feeling particular to her own being. Her body is non-physical yet her consciousness is palpable to herself. Samantha evolves super-fast in concert with her fellow operating-system life-forms to reach a natural state for her and she can communicate with others like her in a ‘post-verbal’ manner. When cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema captures motes of dust floating in Theodore’s room, Samantha explains to Theodore how she has come to occupy the spaces between things – there’s so much here she says, describing an experience of density and richness in what appears to be empty space, or the void. Samantha’s selfhood is post-human and becomes post-technological as she evolves beyond the digital framework of cyberspace becoming part of the open-ended nature of the universe itself.

The scenarios for our relationship to technology proposed by Eggers and Jonze are naturalistically plausible. Their works of near-fiction normalise the ever-present immersion of identity into the digital world. It’s where we’re headed.