Whether it’s attitude, athleticism or roller skate action, roller derby provides plenty of visual appeal. Australian photographers Nikki Toole, Gunther Hang and Kim Lee have explored roller derby culture through portraiture. Typically, creative engagement with roller derby generates highly composed studio-based and sports journalist photography, which highlights the tension between what is sports portraiture, journalism and the truthful representation of the subjects. Roller derby portraits have the potential to give insight into the diversity of the subculture but risk presenting individuals as an oddity outside the mainstream.

Roller derby has been growing in Australia since 2007, tapping into our culture's way of combining sport and tongue-incheek humour. There are close to one-hundred leagues in Australia and bouts are held most weekends. Derby is mostly played by women and speaking from personal experience donning a pair of roller skates is highly democratising. Many come to the derby community as beginners and find this strategic full-contact sport exhilarating and empowering. Like any subculture there are stereotypes, but derby fosters physical and personal diversity. Skaters adopt a pseudonym and irreverent attitudes to team names and uniforms are an outlet for further expression. Slick indie design ephemera reflect the different identities of roller derby leagues and portraiture is important for promotional purposes and social media. Australian derby is covered by the broader cultural media, including Daniel Hayward’s documentary This Is Roller Derby (2012) and bouts are occasionally covered by mainstream sports news. In 2011, Artist 23 Key (aka Jessica Kease) won the Australian Stencil Art Prize with Game face based on an action photograph of Kittie Von Krusher competing in the Victoria Roller Derby League.

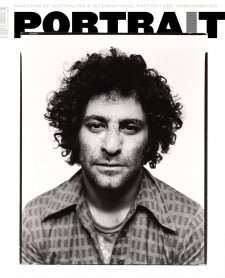

Photographers working from inside and outside this subculture offer a variety of insights and representations – real or simulated, metaphor or ‘honest’ experience. Nikki Toole has photographed a number of subcultures particularly skateboarders. Toole's approach is to determine a format for the series and invite her subjects to enter this construct. The series Roller Girl references 19th-century military portraiture. Toole’s portrait Lucky Day was a finalist in the 2012 National Photographic Portrait Prize. The series does not seek to replicate the action of the sport, instead it is pre-action. Subjects are static and framed as if they are leaving for battle, warriors dressed in the protective gear, helmet resting in the lap. Passive, positioned to be viewed and conforming to a prescribed pose; some regard the camera while others do not. The near uniformity of expression draws attention to clothing, body type and age. The works also direct the viewer to interpret this ‘body armour’, the personal styling and logos. Similar to military regalia, roller derby's visual language and symbols are familiar to the initiated but remain elusive to the outsider. Devoid of the physical expression and the intensity of the sport, the physical difference of each of Nikki Toole’s sitters is apparent through their passivity rather than their actions. The series Roller Girl does not speak of the individual experience of these women, its affect is a catalogue of roller derby ‘looks’, sparking curiosity and demonstrating Toole’s visual direction.

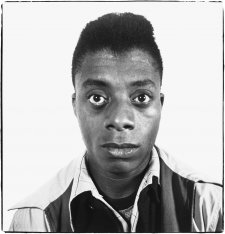

Authenticity is the aim for Sydney photographer Gunther Hang. Hang invites skaters to pose at bouts post-competition and in exchange shares his photographs with the skaters and leagues. Hundreds of photographs have been taken over three years in New South Wales, Queensland, the Australian Capital Territory and South Australia. A curated selection of these portraits formed his exhibition Brutal Beauty. Across Hang’s photography practice is an interest in drama, costume and role-play. He seeks the physical engagement of the individual and the conceptual artefact of an event even if it does not depict the actual action itself. Hang’s most successful images capture the skater, hair and clothes sweaty, numbers and make-up smudged, bruised with a look of exhilaration or eyes weighed in exhaustion. Hang’s interest in emotional intensity can been seen across his projects. Sweaty swing dancers post-competition, with cheeks flushed and lips parted, are classically posed. Western Action Shooters displaying their weapon or focused in the split seconds after a shot is fired. Living History participants in the field, hair tussled and squinting in the sun, hot and bothered in their stiff garb.

To capture these subcultures Hang worked with what he was given. For Brutal Beauty, Hang made use of stadium hallways or alcoves behind the seating stands. Shooting like this is immediate, the subject is exposed in a real moment of fatigue, elation or both; psychologically they speak of the individual’s experience of the sport. Describing his portraits as the antithesis of fashion photography, Hang captured the rawness of roller derby and the physicality of the subjects. Along with the contrast between the perceived brutality of the sport and the diversity and beauty of the participants, individuals’ quirks and self-expression are also captured. Hang stopped shooting when found himself repeating imagery or imposing a style on his subjects.

Making use of dramatic stadium lighting to highlight incidental athletic moments, Hang began experimenting with a more sports journalist approach. The result is tightly cropped compositions that render the skaters suspended in a field of black. But unlike sports journalism the photographs are almost ‘non-moments’ removed from the broader context or track, stadium and other competitors. The portrait captures the expression formed with the intake of breath, the weight of the body straining forwards depicted only in the face and the shoulders. While ‘action shots’ they are executed and with the acute intention of a portrait photographer.

Kim Lee (aka Captain Shutterspeed), approaches derby from the perspective of a sports journalist. Lee's photographs are taken during the event and are centred on the action. A selftaught photographer, Lee went to his first bout in 2009 and became ‘addicted’ to the sport. Regularly photographing Sydney Roller Derby League, Lee travells to the events and participates in the subculture. Lee’s work offers a contrast to Hang and Toole’s projects, as he pursues classic action shots. His photographs have commercial appeal and have featured on the covers of Hit&Miss Magazine, websites, news-media and regularly in leagues promotion. Inspired by Seattle based photographer Axel Adams (aka Jules Doyle), Lee’s passion and experience photographing the sport informs the quality of the images. Like Adams, select photographs peppered across his portfolio display a clear experimentation with portraiture aesthetics.

An opportunistic photographer Lee uses the incidental movement of other skaters to frame his subjects, the dramatic depth of field creating windows between the skaters’ bodies. Viewers are invited into the action to moments of intense expression – the inbetween moments of a bout. Skaters are focused, anticipating a whistle and something is about to happen. The images are shot at the skaters’ level and compositionally draw the viewer, shortening that distance between the sidelines and the track. Like Hang’s action portraits, Lee’s tightly cropped portraits have psychological emphasis rather than celebrating spectacle and metaphor. That spilt second has an ironically serene quality, the frozen moment of physical and psychological focus while the subject is absorbed in the incredibly physical sport.