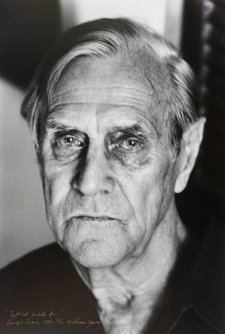

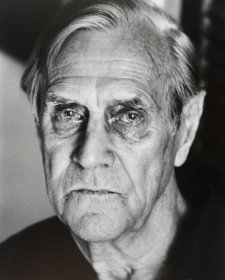

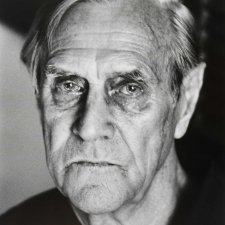

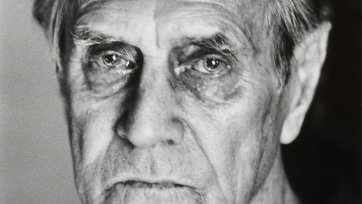

‘Am I a destroyer? This face in the glass which has spent a lifetime searching for what it believes, but can never prove to be, the truth. A face consumed by wondering whether truth can be the worst destroyer of all.’

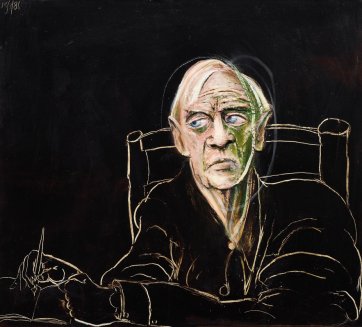

Patrick White wrote these words at about the time Brett Whiteley wrestled with ways to portray the author. Whiteley was on the way to producing a portrait that would end the men’s friendship; in fact, their different ideas and expectations of ‘truth’ were the issue. Yet Patrick White at Centennial Park remains one of the great twentieth-century Australian portraits, the lush trace of the relationship between two of the country’s blazing cultural stars.

A hundred years ago, in 1912, Patrick White was born in London to Australian parents. His wealthy father was a White of the fabled property Belltrees, near Scone, NSW, but when White was a baby his parents settled in Sydney, moving, in due course, to a mansion in Elizabeth Bay. He spent his primary years boarding in Moss Vale and then, at his mother’s insistence, endured four hateful years as a ‘colonial’ at an English school. At seventeen he came home to work for two years as a jackeroo, first on the Monaro, then near Walgett, south-west of Moree. He read literature at King’s College, Cambridge, and remained in London until the outbreak of war, by which time his first novels had been published. For much of his life he was psychologically divided between England, Europe and Australia. As he put it, this country ‘is in my blood – my fate – which is why I have to put up with the hateful place … A Londoner is what I think I am at heart but my blood is Australian and that’s what gets me going.’

During the war, while serving as an intelligence officer in the Middle East and Egypt, White met Manoly Lascaris, a ‘small Greek of immense moral strength’ who was to remain his partner for life. They came to Australia in 1948, bought six acres near Castle Hill, and worked to the point of exhaustion in an effort to live self-sufficiently. White’s asthma was very severe, bringing him close to death more than once, and there were many times when he thought he had lost the capacity to write altogether. However, in about 1951 he began, painfully, The Tree of Man (1955); at Dogwoods, too, he wrote the ripe and difficult novels Voss (1957) and Riders in the Chariot (1961). All of them were published and critically acclaimed in England and the US and soon translated into several languages.

Voss won the first Miles Franklin Literary Award, given for a work of ‘the highest literary merit which must present Australian life in any of its phases.’ Chafing, like many Australian writers, under pressure to write another Great Novel reflecting the country’s new maturity, White wrote to friends in 1958 ‘How sick I am of the bloody word AUSTRALIA. What a pity I am part of it; if I were not, I would get out tomorrow. As it is, they will have me with them till my bitter end, and there are about six more of my un-Australian novels to fling in their faces.’ In 1964, White and Lascaris bought a house in the then-unfashionable Sydney suburb of Centennial Park. Having arrived in the city with only the manuscript of his seventh novel, The Solid Mandala (1966), in Martin Road White brought forth novels inspired by and set partially in Sydney, including The Vivisector (1970), The Eye of the Storm (1973) and The Twyborn Affair (1979). Midway through the Whitlam years, in 1973, he became the only person to have won the Nobel prize for describing Australians.

Brett Whiteley, twenty-seven years White’s junior, grew up in Longueville on Sydney’s lower north shore. A prodigious talent, he left Sydney on an Italian Government scholarship in 1960. The following year, when London’s Tate Gallery bought one of his paintings, he became the youngest artist represented in its collection. Through the 1960s, accompanied by his beautiful wife Wendy and their daughter Arkie, he lived and exhibited in France, London, Tangier and New York. At the end of the decade, after a drug charge in Suva, he returned with his family to live on Sydney harbour at Lavender Bay.

The Whiteleys’ return to Sydney roughly coincided with the beginning of Patrick White’s career as a public radical (at the end of 1969 he signed a petition opposing the Draft). As a ‘Nobelist’(a term he detested) and Australian of the Year, the author became increasingly famous and was in demand as the cranky public face of dissent. Assuring his listeners that ‘small-scale passive resistance can work wonders, as some of you have found out in your private lives’, over time he spoke at rallies against Australian subservience to Britain, the USA and Japan; threats to turn Centennial Park into an Olympic Games venue and build highrises in the Rocks and Woolloomooloo; the monorail; the development of Australia’s nuclear facilities and the Bicentennial celebrations. ‘I still have this photograph of a fat old codger in beret and tweed suit surrounded by youthful supporters, advancing down George Street towards the Town Hall under one of our banners’, he wrote with pride and embarrassment at the end of the 1970s.

White had purchased his house with part of his inheritance, but the period after he won the Nobel prize (the cash component of which he gave away) was the only time in his life that he earned a substantial income from writing. He and Lascaris lived frugally in Martin Road; travel and substantial pieces of art (most now in the Art Gallery of New South Wales) were their only major indulgences. White resisted Whiteley for some time, dismissing him as an imitator of Francis Bacon, whom he had known in London. Yet not even White could hold out against Whiteley’s ravishing shows at the Bonython Gallery in Paddington in 1970 and 1972. Over the decade, as Whiteley turned to series of paintings of waves, interiors, the harbour, and coastal landscapes, White bought significant works by the painter, and they saw each other socially. White told a friend that Whiteley made them touch his hair, ‘which is a mop of tight little corkscrew curls which look silky, but feel as though they have been rubbed with resin’. To Lascaris, it felt like touching a strange animal. In 1972 the artist urged the couple to try mescalin, but they feared looking ridiculous at their age. On the night of the Dismissal, 11 November 1975, the Whiteleys were amongst dinner guests at Martin Road who listened incredulously to the wireless throughout the meal. ‘Brett Whiteley passed out on a divan in the middle of the room, which we keep for that purpose, but which nobody had made use of till then’, White recalled. In 1978, Whiteley became the first artist to win the Archibald Prize for portraiture, the Wynne Prize for landscape and the Sulman Prize for genre painting all in the same miraculous year.

These were Brett Whiteley’s various ideas for his immediate future at the start of April 1979: the first, to introduce into his body only vegetables, fruit, distilled water and maybe a bit of milk; the second, to travel like a gypsy, beginning in China; and the third, to remain as he was, and paint four portraits over the coming two years: of Albert Einstein, Howard Hughes, Patrick White and Sir Kenneth Clark. (Some years earlier, Whiteley had offended half of England by observing that John Christie, the perpetrator of ghastly murders and necrophile acts at 10 Rillington Place and the subject of a hideously evocative series of paintings by the artist, bore an uncanny resemblance to Clark, the country’s august authority on art.) As he outlined his plans, he gave his interviewer a list of his favourite things:

Word: avert

Colour: white

Bird: Japanese white ibis

Food: near-raw steak and milk

Drink: crushed chilled apricot

Country: China

Sound: Bob Dylan singing ‘I Want

You’ at the Sydney Sports Ground in

April 1978

Painter: Turner (at sea)

Dog: those without collars

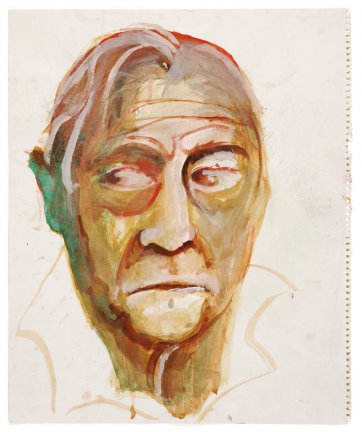

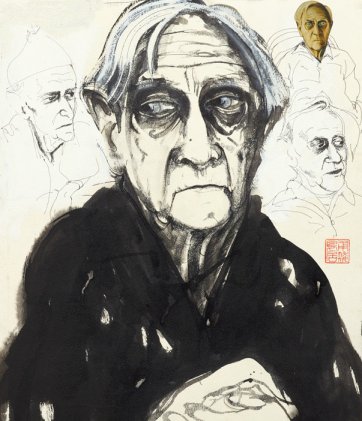

It transpired that within a few months, he was painting White. He explained what he was trying to do: ‘Patrick was an exercise. Could I incorporate a portrait with Australia and his world? Could I make a vision of the feeling of his literature plus how he lived, and the complexity of him as a person, his humour, his bitchiness, his pronouncements? I think he’s really a king of a person, the only one in Australia that really is a judge in many things. I’m not a reader and I’ve only read two of his things, but they’ve had such an enormous effect on me that I’ve felt intimidated by the mind that could weave such a thing. The Solid Mandala is the one I cherish. He would only give up more to the picture as he believed I could make a vision of it. I wanted from him love, hate; I wanted from him the literature that he effected and how it influenced him; things that he loved so enormously; the best of his work, his dogs, his private life. And he is an enormously private person. The closer I could paint it the more he gave. I worked on the head for two months and was enormously dissatisfied. Then I went away for a week with a piece of paper exactly the same size as his head, and just concentrated on a vision of his head, and clinched an image that was an anchor … I’d got it to look like what I saw. I cut it out and put it on the picture and then everything in it became subordinate to that vision. It took about 1 ½ months of structure, a week of precision and then it took a day of – I don’t know the word for that.’

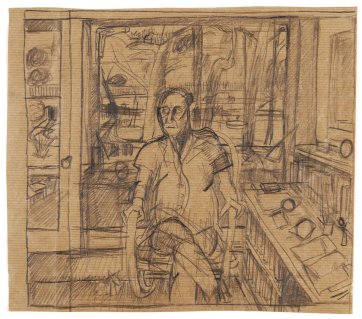

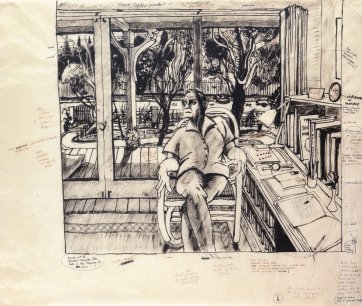

In contrast to his earlier, fragmented and fanciful portraits of Rimbaud, Baudelaire and Van Gogh, Whiteley’s portrait of White shows the writer sitting in a fairly ordinary position in his study, in the centuries-old tradition of portrayals of the guildsman at his work bench, the explorer with his maps or the zoologist with his specimens. These sorts of portraits, and those inscribed with mottoes, tags, names and so on, have been described as ‘augmented’ portraits, because they offer not just a likeness but deliberate clues as to character or biography. They appear to present documentary evidence of the sitter’s environment. So, we assume, for example, that White sat on a Thonetstyle bentwood rocker, put out seed for birds and set the sprinkler on his grass. Yet portraits of this kind are not always faithful to facts, and this one certainly is not. Here, the ‘books’ the spines of which bear the names Stendhal, Mozart, Chekhov, Goya, The Solid Mandala and so on look more like ring binders, on which White has carefully and rather poignantly written labels in differently coloured textas. Unfairly, Lascaris looks like a saucy English comedian in his photograph. The significance of the cone shell is unclear (is it significant?). The panes of glass behind White are far too large for a domestic space.

The gate appears to be a mere step up from the footpath, whereas the block was steeply elevated from the street. The greatest affront to fact is that the view gives east, across Martin Road to Centennial Park; yet the Opera House and Circular Quay (situated to the north, beyond the undulating CBD) are visible in the top left corner. The glimpse of the Opera House is perhaps Whiteley’s effort to ‘incorporate [sic] a portrait with Australia and his world’. White himself described Sydney as ‘my native city’ and ‘what I have in my blood’ (as well as describing Joern Utzon, whom he met on the Royal yacht Britannia, as ‘handsome as they come’). Yet a case could be made for the portrait’s referring strongly to Whiteley himself; a similar stylised Opera House appears in his own Self portrait in the Studio of 1976, and the magnolia – its leaves in exactly the same arrangement – is the eponymous star of a still life he painted in 1977–78.

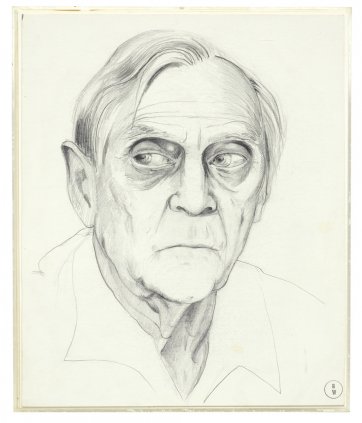

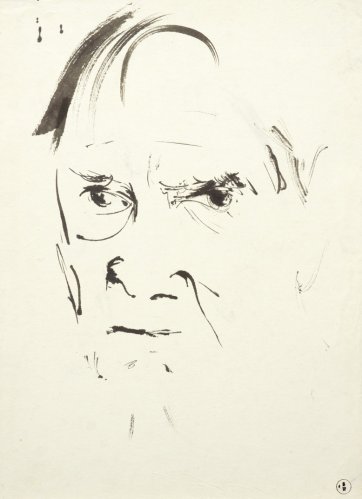

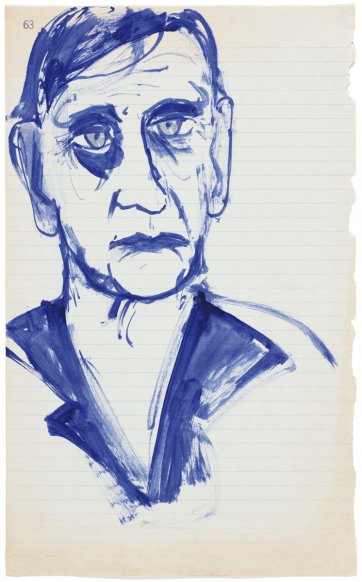

Most of the portraits Whiteley made along the way to the ‘big one’ relate closely, too, to various phases of the artist’s oeuvre. The three portrait heads are not unlike drawings he made in the London Zoo in the 1960s (to say that the drawing of the author looks rather like the Drawing of an ape of 1965 is to insult neither White nor Whiteley – after all, Sartre recalled, in La Nausée, his aunt’s telling him that anyone who looks in a mirror for long enough will see a monkey.) The head in blue ink calls to mind the white ceramic vessels and platters decorated with intense blue nudes, magnolias and stylised foliage that Whiteley made around 1979–80. The exclamation mark in From walks in Centennial Park with Patrick White appears in Alchemy. The arresting ‘straight’ drawing in White, Whiteley is unusually observational. Although White looks paranoid in it, it is by no means a caricature. The detailed pencil sketch is devoid of Whiteley’s seemingly inescapable sinuosity of line; somehow, the sketch skipped the dominant aesthetic gene that reasserts itself in the boneless arms and dangling legs of the author in the finished work.

The big portrait and its related works have not been shown together since they were exhibited at the David Reids’ Gallery in Paddington in the autumn of 1980. (A point of interest for grammar pedants: the Gallery was an exhibition space available for hire from David Reid and his father, also named David Reid; hence the plural possessive apostrophe.) The show comprised a series of largerthan- life-size oil, steel and gold leaf Crucifixions, depicting Whiteley’s friend Joel Elenberg, who was soon to die of cancer; lyrical landscapes from the region around Oberon; a portrait of Elenberg, and the portrait of Patrick White with many studies for the work.

The portrait of White, along with the annotated sketch indicating Whiteley’s developing vision for it, was chosen by Andrew Andersons, Principal Architect of the extended and refurbished New South Wales Parliament House for its new collection. Up till the mid-1970s, the Parliament had borrowed works from the Art Gallery of New South Wales, but with ample exhibition space now available, the time had come for acquisition of works ‘representative of the best contemporary art in Australia with an emphasis given to works by artists resident in New South Wales’. By the time Andersons arrived at the exhibition, all the landscapes had sold, but the portrait of White struck him as a work that would appeal to key figures in the Wran Labor government. White asked for a meeting with Andersons, because he was concerned about where his portrait would be displayed, and who would be likely to see it. Andersons explained that it was destined for a position of eminence at the entrance to the suite of the Premier, where it wouldn’t be exposed to public scrutiny. When Barrie Unsworth became Premier in July 1986, he asked for the portrait to be removed from its position; but when Nick Greiner became Premier in March 1988, he is said to have had it reinstated.

Patrick White knew that ‘where I have gone wrong in life is in believing that total sincerity is compatible with human intercourse’; yet he became disenchanted with Brett Whiteley, as he had with so many others lacking ‘pureness of heart’. In time, White focused his increasing general disappointment with the younger man on his incorporation into the portrait of elements he had furnished at Whiteley’s request as inspirational, preparatory material – to wit, the list of loves and hates. He wrote to him in October 1981, repudiating ‘that vein of dishonesty from which so many of your acts and attitudes stem. When you asked me to write down my likes and dislikes for you alone before you painted the portrait, and then I found them pasted on the thing itself, that really rocked me, but I swallowed my feelings at the time. However, one sees that this kind of dishonesty is behind everything you do … I find this very distressing in one I wanted to accept as a friend.’ Whiteley wrote back to him four days later, ‘You make me feel wicked as though I’ve ripped you off … your fidelity of accuracy is so deeply moving why would you deny another man’s attempt to show some truth … so you think I’m dishonest I’ll just have to reset the computer and press forget’.

Patrick White died in 1990. There was no funeral; his ashes were scattered by Lascaris in Centennial Park. In what amounted, to White’s friends, as his memorial service, David Marr’s superb biography of the author was launched at the Art Gallery of New South Wales beneath the Whiteley portrait. Alone, Whiteley died of an overdose in a motel in Thirroul, New South Wales in the winter of 1992. Lascaris, publicly acknowledged by White as the mainstay of his life and work, died in November 2003 at the nursing home established in Lulworth, the grand Elizabeth Bay house in which White had lived as a child. Wendy Whiteley lives alone in the home she shared with Brett in Lavender Bay. The unsold Crucifixions hang there.