People in Idle hours are not all taking a break from constructive activity; but they are almost all taking a break from self-consciousness, angst and restlessness. Idle hours is an exhibition of images of contentment – images of people disconnected, in some cases, and concentrating, in others, but all of them at ease with who and where they are. Most of them are at home.

In depicting family, friends and strangers doing nothing much, artists enter into an extended pact of quietude with their sitters. Brought together, such works trail the tranquil circumstances of their creation into the gallery space; contemplating the paintings, prints and drawings in the exhibition, the viewer is drawn into the silent stillness of the situations depicted.

Idle hours takes its name not only from the theme, but from the layout of the show – the works of which, regardless of the year in which they were made, are hung according to the time of day or night that they depict. The first room of Idle hours contains pictures of people waking up, breakfasting and enjoying the sun. By the entrance to the second room, the first person has fallen into an after-lunch siesta; others work through a basket of ironing, pick up their sewing, or sit down to afternoon tea. As the afternoon lengthens, people enjoy a beer, ease into a bath and watch television. In the last room, as night falls and deepens, others prepare dinner, put on a record or settle in for some serious talking. Moving through the span of a waking day, Idle hours is an exhibition about the quality of light as well as one that emphasises the commonality of middle-class Western experience.

From the gay blues, pinks and yellows of William Robinson’s Morning and Hilda Rix Nicholas’s Sylvia and friend at Mosman, to the velvety black, gold and suede-beige of Jenny Sages’s Red shoes from Vinnies and Hugh Ramsay’s A student of the Latin Quarter, the visitor to Idle hours moves from the possibilities of the fulgent morning into the soft cover of darkness.

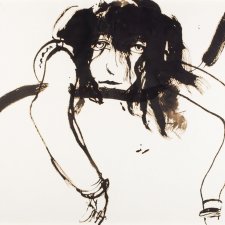

Some of the works in Idle hours are typical of the artist’s practice: of many works by Hilda Rix Nicholas that could have been included, for example, there are two; of many by Agnes Goodsir, there are three. Others seem unusual. Ken Done’s hazy, wistful self portrait Trying to paint on a Monday is unlike his brash and hard-edged commercial designs. Rick Amor’s painting of his baby daughter, Zoe, is not readily recognised by people accustomed to his disconcerting, lonely views of Melbourne streets and empty museums. And viewers accustomed to Brett Whiteley’s agonised self portraits may be surprised by the absence of stylisation in his beautiful drawing of his wife, Wendy sleeping, or the love that bleeds from his Wendy drunk 11pm.

Almost without exception, Idle hours comprises pictures of serene and equable- looking individuals. Many of the works in it are small. Paradoxically, however, one of the exhibition’s most engaging portraits is distinguished not only by its giant size, but by the irascible expression of its subject – Dr John Shera, father-in law of the Queensland painter, novelist and filmmaker Davida Allen. Allen won the Archibald Prize for 1986 with this portrait of her husband’s elderly father pouring water on his young trees, the sun hot on his back, the hose a cold vein against his leg. In the course of the painting’s creation, she lashed the wet paint with branches taken from Dr Shera’s garden. Though more arresting than gentle, better viewed from a distance than contemplated closely, it is an ideal work for Idle hours because watering, a constructive pursuit that requires minimal effort, is an activity that cannot be hurried. Ideally undertaken in old and scant clothes, it affords great opportunities for rumination.

Often, the people with whom we feel most at ease are partners and family members – even in-laws – and it is no coincidence that more than half of the works in Idle hours depict the artist’s partner, children, parent or sibling. It is a privilege of a lover or family member to observe a sleeper, and a long wall of Idle hours is devoted to slumbering figures, most of them well-loved by the artists who depicted them. Kevin Lincoln evokes the utter obliviousness of his grandson in a spare drawing of him flat on his stomach, head turned to one side. Rod Ewins depicts his new bride, Bev, drowsing in their English flat, her clean hair falling across her face and her robe lying open over her pale breast. And alone in their seaside house, Ivor and June Hele repeatedly enact an erotic tableau, the artist scrutinising every crease of his prone, compliant model; sometimes she is naked, her hair loose around her, but more often she wears bits and pieces of garments and outfits – a frilled petticoat, silky pants, seamed stockings, high shoes or a soft slip. When we contemplate images such as these in Idle hours, we do not just look at the insensible subject, but picture the quiet minutes in which the artist rendered the recumbent figure; the minutes that passed while the humdrum turned into art.

Grace Cossington Smith travelled to England and Germany before the First World War, taking a motoring holiday with her father and sister Mabel. On her return she moved into the new family home in the undulating suburb of Turramurra north of Sydney, where her father had built her ‘a dear little studio down at the bottom of the garden, a perfect studio’. She was to live at Cossington for the next sixty years, drawing and painting domestic scenes, objects and flowers. As a young woman she often sketched her siblings, Madge, Diddy and Gordon as they read and snoozed in the house and garden.

Several of these drawings are featured in Idle hours, including a lovely charcoal of Madge, rendered with a tender kind of objectivity as she dozes through a warm Turramurra afternoon. It was in her first few years at Turramurra, too, that Grace began to experiment with coloured paints, rendering her surrounds at different times of the day and night; but there are comparatively few paintings in which the Smith siblings appear as themselves. For The sock knitter 1915, its strong forms and bright blocks of colour revolutionary in Australian art, she used her sister Madge as a model, setting her looking upright and intent on making a sock to send to a soldier. There are other paintings in which her sisters are pressed into service in this way; but it is simply Diddy who stitches in the bright light and fresh morning air of the Open window.

Some of the loveliest drawings of a sleeper in the show are by an artist at the peak of his career to date, Nicholas Harding, whose retrospective exhibition at Sydney’s SH Ervin Gallery coincides with Idle hours. Harding has built his reputation on mighty drawings of railway tracks and scungy streets of inner Sydney, rendered in ink scored deeply into thick paper, and lush, scintillatingly atmospheric paintings of the holiday coast a few hours to the north. He is also an accomplished portraitist; his portrait of John Bell won the Archibald Prize in 2001, and Bob’s daily swim, included in Idle hours, was a highly-commended key image in the Archibald of 2005. His paintings are typically thick impasto (never thicker than in his portrait of art dealer Rex Irwin, included in Idle hours, which requires several art handlers to lift it). The exhibition also features six captivating drawings Harding made of his son at various times, ranging from quick sketches to beautifully refined work. Reflecting on the gift of spending time with loved ones, Harding writes that ‘to gaze upon those whose company holds profound meaning stirs many, sometimes conflicting, emotions.

The joy of presence and promise tempered with anxiety for possible jeopardy. Drawing slows down the fleeting moment, attempting to grasp the impermanent and is an empirical affirmation of this intimate bond. To look to the point of fascination is a purpose of drawing and to draw our son is an act of devotion.’

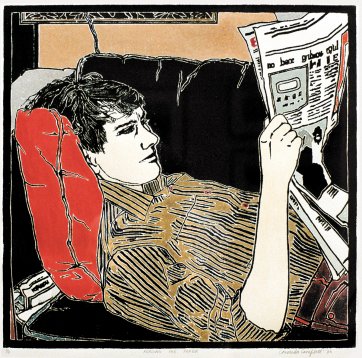

In Sam reading, one of the quick drawings on perforated paper that was to hand, Sam lies with his head propped up rather awkwardly, chin buried in his chest; his eyes burn unswervingly on his book, his large shorts are drawn up high. His foot flops sideways, rolling his whole leg over. In this drawing, seemingly utterly unposed, Harding really does seem to have succeeded in his attempt to stop time.

Like several subjects of works in the exhibition, Sam appears transfixed by his book. Yet relaxation is not always expressed through inertia. Children, especially, are often most at ease when upside-down or sideways, under the table or behind the sofa. Brian Dunlop and Fred Williams made paintings and prints of their daughters this way. Dunlop, an artist well-known for paintings of solitary figures in empty interiors, often drew his children Sophie and Claudia when they came to stay in his Fitzroy house in the 1980s. In Dunlop’s sunny living room, Claudia weaves her fingers in the wicker, idly enjoying the room viewed from an angle.

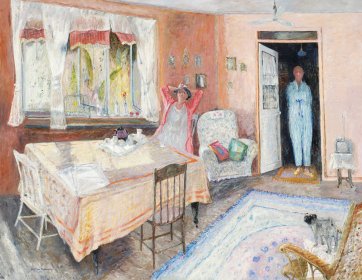

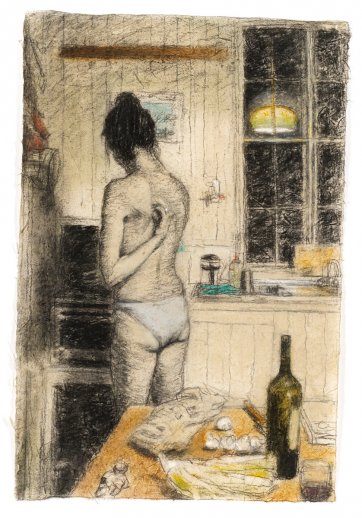

Looking at Girl resting in a wicker sofa we can feel the hard canes her fingers grip, and remember how when viewed from floor level, the ceiling of the room looks much more spacious than the floor; a place of great possibilities. Jenny Sages is well-known as a portraitist; her paintings of Emily Kngwarrey and Helen Garner are amongst the most popular works in the National Portrait Gallery. In 2002, Sages made a remarkably intimate series of drawings of her adult daughter, titled Red shoes from Vinnies. Sages’s daughter was in her early thirties and living on a property outside Toowoomba, Queensland, with her family when she contracted Ross River fever. Her mother went to help her, but her lasting gift was this visual narrative, showing the young woman moving from her bedroom to the kitchen and preparing a meal over the course of one afternoon and evening.

As her mother observed, ‘her time clock as a mother told her that the children needed feeding, she attended to that as always with care, after they were fed she wiped down the old kitchen table and with despair gave into her illness again.’ Sages recalls ‘she had bought the red shoes from Vinnies for five dollars several weeks before, they seemed to be the only bright spot in her life at that time.’ The works glow with the yellow light of the hot weatherboard kitchen against the blackness of the windows, punched with stars. The last drawing in this otherwise observational series shows the subject’s all-but-naked body braced in the red heels, knees locked back. The kitchen stools are now unoccupied, two little spotted glasses sit starkly on the table; but the young woman’s face is blurred: a blank. In effacing her, Sages poignantly expresses both her daughter’s exhaustion, and her own powerlessness to make her well. Both of them must simply wait.

Moving as it does across the span of a day and night, its subjects ranging from babies to the elderly, Idle hours is a microcosm of life’s brevity, the necessity for everybody to come to terms with his or her essential solitude as well as the love and learning that make living worthwhile. Cressida Campbell is a Sydney artist who works in a studio in the back garden of her home in Bronte, listening to the wireless and talking on the telephone while she builds up the delicate details in her prints of plants, vessels and interiors. ‘It’s a slow process,’ she has said. ‘You can’t do it faster than it needs to be done.’ A few years after they met in the early 1980s she made a portrait of her husband, writer, critic and editor Peter Crayford, rustling his paper in repose. Cressida Campbell’s and Peter Crayford’s is a moving love story, documented in Crayford’s November 2008 Spectator article describing his recurrent illness and his determination to produce a book that would do justice to his wife’s beautiful work. Although they have been together more than twenty years, ‘I think both of us fascinate each other’, Crayford has said. There were tough times ahead for the graceful couple; but rendered here in finely-modelled, youthful profile, Crayford gives off a lovely air of equanimity.

Almost nobody is smiling in Idle hours. Some of the men and women depicted are so self-contained that we might question whether they feature in portraits or still-life compositions. But the human presence in the works means that many of them seem to invite us to listen as well as look; if we do so, what we will hear is a limpid stillness. Idle hours is balm for increasing numbers of us who wonder why we work longer hours than our parents and grandparents; why we seldom finish reading the books piled by our beds; why we spend so much time in the office and shopping mall. It invites us to ask when we began to accelerate; to become little more than a tangle of traits, habits and needs that we don’t admire in others. It is a show about self-possession, constructive routines and close attention to loved ones – about contentment, and complaisance. On reflection, in fact, it is a show of happy portraits.