One of the attractive aspects of the collection of the National Portrait Gallery is that it is often possible to pluck out two or more portraits that are totally different in character, and trace quite significant links between the sitters.

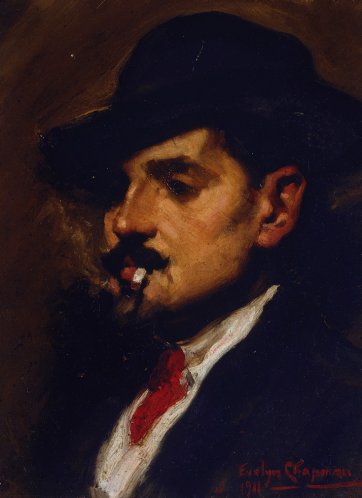

As portraits, Arthur Murch’s greenish bust of Antonio Dattilo- Rubbo and Evelyn Chapman’s dark, dashing self-representation have little in common. Yet as individuals, for a short, heady time, Rubbo and Chapman were closely linked.

When the English-born artist Julian Ashton set up an art school in Sydney in the mid-1890s, aspiring artists raced to it like parched kangaroos to a waterhole. In 1897, a rival instructor in the form of a charismatic Italian, Antonio Dattilo- Rubbo, arrived in Sydney having gained his art teaching qualifications in Rome and Naples. Amidst a number of romantic explanations for why he chose to – or had to – leave Italy, there is one common factor: he boarded the boat without a clear idea of where it was going. Soon after arriving in Sydney, speaking next to no English, Rubbo set up his atelier in Rowe Street, not far from the Bulletin headquarters. Rowe Street – now totally redeveloped – was then home to tiny shops above which were studios and poky flats reached by narrow, dark wooden stairs. Students and models, including the old men that Rubbo particularly liked to paint, would clamber up to the artist’s premises to be met, one pupil recalled, ‘by the blended aroma of turps and omelette that constantly floated through the doorway.’

In his twenty-eight years as instructor for the Royal Art Society, Antonio Dattilo-Rubbo was a pugnacious champion of the work of the artists now recognised as Australia’s first modern painters. In 1916 he challenged one of the members of the Society to a duel – offering him the choice of pistols, swords or fists – after Roland Wakelin’s Down the Hills to Berry’s Bay was rejected for the RAS annual exhibition. (Though the challenge was shirked, and the painting exhibited, Rubbo’s grandson Mike recalls that late in life his ‘Nonno’ carried a wizened human ear in his pocket, purportedly nabbed in another stoush that went ahead.) Like Wakelin, Roy de Maistre fell under the spell of Dattilo-Rubbo’s enthusiasm for the colour and light of French postimpressionism; the Signor spoke at the opening of the two artists’ joint ‘Colour in Art’ exhibition in 1919. ‘Get rid of the brown!’ Grace Cossington Smith recalled him saying; she did so, and he nicknamed her Mrs Van Gogh. She described him as a ‘marvellous teacher … very keen about colour and the modern masters. He was the only one in Sydney at that time who knew anything about Cezanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh. We had very interesting lunch hours, because [Signor Rubbo] always read something interesting to us about the contemporary painters at the time. I remember so well Margaret Preston coming in, and she gave us a very interesting talk on her methods.’ In 1919 Rubbo was thrilled by an exhibition of the comparatively brutal work of Hilda Rix Nicholas; art historian John Pigot quotes a letter of Grace Cossington Smith’s, in which she tells a friend that since seeing the exhibition, ‘Signor Rubbo has not been sane!’

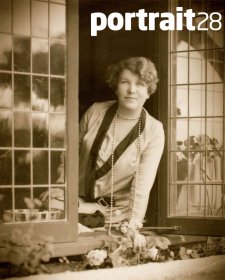

Hilda Rix Nicholas had washed up in Sydney after returning from Europe, where, by early 1918, life had become too hard. In the prewar years, artists moved constantly back and forth between Australia and Europe. Thea Proctor, for instance, left Sydney in 1903, returned for a while in 1912, and was on the boat heading back to London when war was declared in 1914. Norah Simpson, a student of Rubbo’s, visited London and Paris intermittently between 1911 and 1915 and come back brimming with modernist ideas that she shared in his classes. Working alongside her in the early days was Sydney-born Evelyn Chapman, who trained with Dattilo- Rubbo for about four years in her early twenties. Chapman herself travelled to Europe with her parents in 1911, the year she painted both her own self portrait and the portrait of Rubbo that was later to be acquired by the Art Gallery of New South Wales. In Paris, she continued her studies at the Académie Julien. She returned to Australia briefly in 1914 and sold a painting to the Art Gallery of New South Wales before resuming her training at the Bushey School of Art in Hertfordshire. Although by 1911 Dattilo-Rubbo was married, with a baby son, he evidently missed Evelyn, whom he called by the pet name Trio. He sent her a little painting of gum trees, inscribed ‘To my dearest TRIO Chapman. With my heart beating and my brushes blending, sending this to you. Antony.’

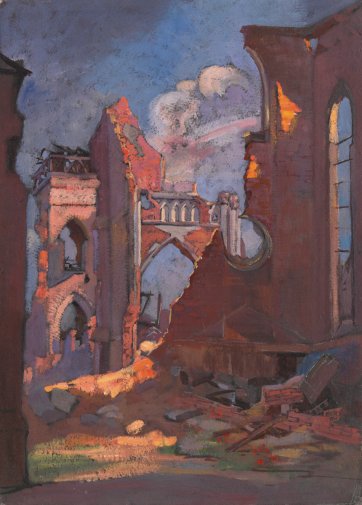

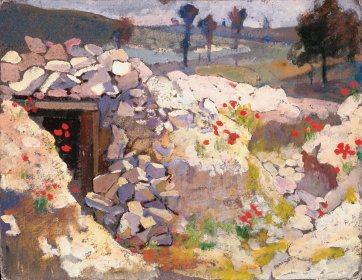

Having lived abroad for many years, a few weeks after the end of World War I Evelyn Chapman took the opportunity to visit France with her father, who, though an organist by profession, was attached to the New Zealand War Graves Commission and went to France to oversee the burial of New Zealand’s war dead. Consequently, Evelyn Chapman became the first Australian female artist to depict the blasted battlefields, towns and churches of the western front. Painting in tempera on felt paper, she rendered scenes of devastation and regeneration in high colour – orange against olive and brown, bright blue and poppy red – the accents of her old teacher, perhaps, susurrant in her head as she worked. Having painted in a studio in Dieppe for a time, she visited Australia in 1920 fresh from success at the Paris Salon. Five years later, she married a brilliant young pianist, George Thalben-Ball, who became famous during his long career as the organist and choir director at London’s historic Temple Church. Once Evelyn married, she stopped painting. For the rest of her life, she lived in England, only returning to Australia for a visit in 1960, the year before she died.

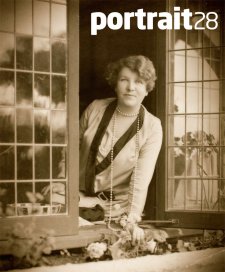

Her early departure from Australia and her truncated career are two reasons why Evelyn Chapman is scantily represented in Australian galleries. Another, according to art historian Catherine Speck, is that although she did not know it, her father bought most of the works she exhibited. It is possible that Dattilo-Rubbo, a member of the War Memorial Advisory Board from 1919, influenced the acquisition of a number of Chapman’s works for the Australian War Memorial in 1920. Of the eight works by Chapman now in the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, all but the portrait of Rubbo were donated by the artist’s daughter, Pamela Thalben-Ball, in 1976. It was Pamela Thalben-Ball, too, who gave Chapman’s bold self portrait to the National Portrait Gallery in 2007. This painting is thought to have been purchased by Bulletin founder Jules François Archibald, long before he endowed the eponymous portrait prize. However, before Archibald took delivery of it, Chapman’s father photographed it, and in this way, though she had never been able to locate the painting, Chapman’s daughter was familiar with it. Last year, it came up for auction and was spotted by her friend, Doug Moran, who bid for it on Thalben-Ball’s behalf. Happily, upon the Gallery’s acquisition of Chapman’s self portrait, Chapman and Thalben-Ball became the first mother and daughter artists to be represented in the collection (Thalben- Ball’s portrait of Kay Cottee, pictured on the back cover of the last issue of PORTRAIT, was an early acquisition of the National Portrait Gallery).

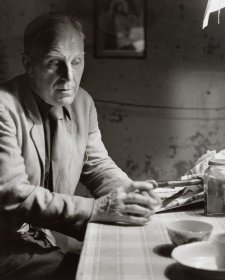

Rubbo’s handsome countenance and flamboyant costume ensured his popularity with portraitists of all kinds. Miriam Moxham, another of Rubbo’s students, painted a portrait of him wearing his trademark red bow and flourishing his perpetual cigarette. His compatriot Girolamo Nerli also painted him wreathed in smoke, his moustachios twirling. Arthur Murch, a student of Rubbo’s between 1921 and 1925, won the Society of Artists’ Medal in 1935, the year he sculpted Rubbo. Later, he won the Archibald Prize. Rubbo, a prolific portraitist himself, entered the Prize eighteen times. Struggling to find tales of Rubbo that were suitable for recounting in the Art Gallery of New South Wales magazine, Erik Langker chose to relate the story of a portrait that he painted on commission for a ‘society lady’. When she saw it she refused to pay for it, saying that none of her friends thought it resembled her in the least. Saddled with the work, the artist altered it, covering the woman’s head with a spotted handkerchief, furnishing her with gypsy accessories and adding cards and a crystal ball to a table in the foreground. When the painting was exhibited as The Gypsy Fortune Teller, the sitter expostulated that she and her friends were embarrassed by the work. Rubbo feigned puzzlement on the basis that it was her friends who had said it was nothing like her in the first place; the furious woman agreed to pay for the painting providing it was taken off display.

Though his own paintings are virtually forgotten, Antonio Dattilo-Rubbo was central to the Sydney art scene throughout the early decades of the century, a time when for a passionate small group, art was as vital as breathing. By the time Evelyn Chapman gave up painting, uneasiness over the nature and future of art had intensified all over the world, even in Sydney, where Thea Proctor fancied she was fired from Julian Ashton’s school in 1923 ‘for giving the students dangerous thoughts’. In the ensuing years the city’s art ‘community’ split into several sniping factions. In 1926, with a weary George Lambert, Proctor formed the Contemporary Art Society, inviting de Maistre, Wakelin and Cossington Smith to join along with Margaret Preston – although soon the two women fell out permanently, partly because Preston favoured the imposition of tariffs on imported art. In 1932 Rubbo was created a Knight of the Order of the Crown of Italy; now styled Il Cavaliere Antonio Dattilo-Rubbo, he quit the Royal Art Society and aligned himself with its open rival, the Society of Artists, in 1934. By the mid-1930s, however, modern art had outstripped his capacity to accept it. One of his sons died in 1933, and his wife died in her kitchen a decade later. In the interim, Rubbo was briefly interned under suspicion of disloyalty to his adopted country. Increasingly debilitated, attended by his former student Frances Ellis, who took over his school, he ended his days painting in the silence of the suburbs.

The story of Rubbo has an idiosyncratic coda. Many years after he died, in the 1980s, Arthur Murch and Rubbo’s grandson Mike went to Rubbo’s former home, Vesuvio in Prince Albert Street, Mosman, with a specific purpose: to allow the artist a last look at his final studio before it was demolished. They took the bust that Murch had made, photographing it in the studio and in the garden before they came away. Later, after Murch had died, his widow gave the bust to the National Portrait Gallery – where, fortuitously, Rubbo and Chapman, teacher and student, were reunited ninety-six years after they made their first farewells.