Although the tough, weathered, hard-drinking bushmen of the kind mythologised by writers like Banjo Paterson and Henry Lawson are popularly associated with the character of late nineteenth century Australia, it was also a time when alternative ideas about identity began to come into play. Like earlier ideals of masculinity, these ideas are traceable through the changes in facial hair fashions adopted by Australian men. The period between the 1850s and the 1880s may have been the era of beards as badges of the wise, protective, resourceful or vigorous. But the decades that followed might be considered those when dignified restraint and greater attention to grooming took precedence and when, in Australia, the rugged, anti-authoritarian bushman began to be replaced by the urbane, responsible and educated chap.

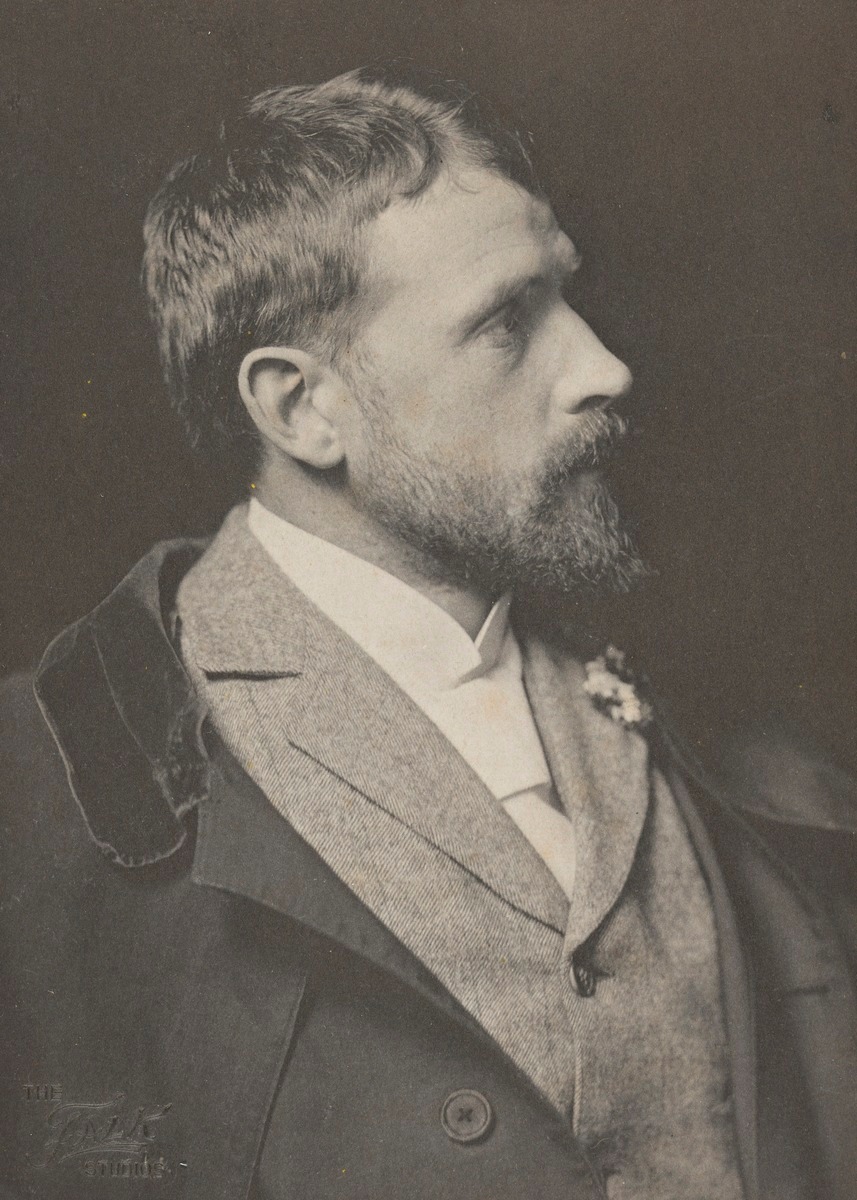

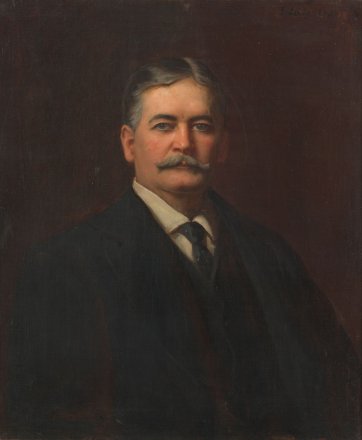

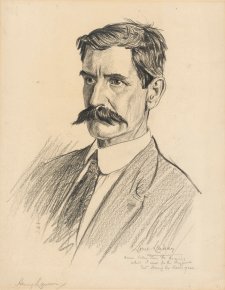

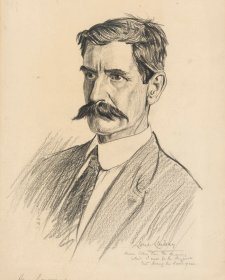

An increasing emphasis on tidiness and tailoring was characteristic of men’s fashions in Britain and America in this era. Beards retained some popularity, but were more commonly seen in trimmer, more manicured or sober styles. Older men in particular might have maintained hirsute appearances. Sir Henry Parkes, for example, was famous for his long, white beard – a style befitting the age and wisdom of the ‘father of Federation’. But it became more typical for younger men to wear their hair short and to cultivate moustaches in bushy, drooping or pointed styles. In Australia, the trend for mos, smaller beards and clean-shaven faces could be argued to demonstrate the mood of youthful nationhood that began to take hold in the time leading up to Federation in 1901. Australians, by this reasoning, began during this period to assert, consciously or otherwise, a sense of themselves as responsible, healthy and hopeful – a sunny, outdoors breed known for sportsmanship and egalitarianism and not just as hardened frontiersmen. The boys’-own-annual type of chap – fit; charming and easy-going; comradely; reliable if adventurous; capable of heroism; and a dab hand with the bat – was one of a number of models that resonated with Australian men at the turn of the century. These qualities were also seen as typical of Australian soldiers in the First World War. By this time – assuming newspaper advertisements and barbering manuals are sound evidence – men were beginning to take personal grooming more seriously, using a variety of products and remedies to smooth, sculpt, dye, wax or lighten their hair. Advances in scientific understanding demonstrated that diseases were caused by microbes and not miasmas, discrediting the old argument that facial hair had health benefits.

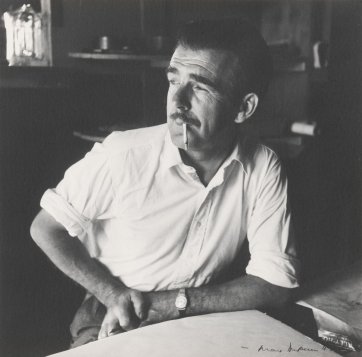

Wartime strengthened the preference for more serious and dignified men’s hairstyles, partly because of the increased numbers of men in uniform and who were thus bound by regulations regarding the degree and style of facial hair growth. The moustaches sported by the likes of Lord Kitchener (he of the massive mo featured in the ‘Your country needs you’ enlistment poster) and the Australian general Sir John Monash might therefore be considered symbols of bravery, heroism and patriotism. By the 1920s and 30s, the fresh-faced, clean-cut look was very fashionable and it was typical for men to wear their hair cut very short at the sides, parted, and doused with brilliantine. The effete, pointed beard known as the ‘Van Dyke’ was also a typical look of the period, along with moustaches in various styles, often influenced by the suave Hollywood looks of actors such as Errol Flynn and Clark Gable; and by the fashions imported by artists and other expatriates returning to Australia after extended sojourns abroad.