- About us

- Support the Gallery

- Venue hire

- Publications

- Research library

- Organisation chart

- Employment

- Contact us

- Make a booking

- Onsite programs

- Online programs

- School visit information

- Learning resources

- Little Darlings

- Professional learning

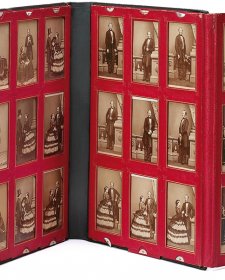

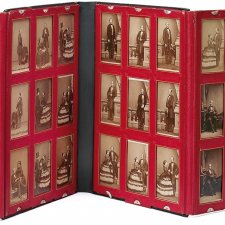

Victoria (1819-1901) was queen of Great Britain and Ireland from 1837 to 1901, from the age of eighteen until her death nearly 64 years later. Born Princess Alexandrina, she was the granddaughter of George III – for whom James Cook claimed the east coast of New South Wales – and became Queen Victoria after the death of his son William IV, her uncle. Victoria’s then-record reign was notable for British industrial expansion, economic progress and the increase of the British Empire. In the early years she took much counsel from her first prime minister, Lord Melbourne. Three years after taking the throne she married Albert, a gentle, well-educated German prince who became her de-facto private secretary, advising her in all matters, especially to do with foreign and humanitarian affairs, progress and arts and culture, as well as fathering her nine children, most of whom married into European royal houses. When Albert died in 1861, Victoria fell into a decline, rarely appearing in public for years, during which the popularity of the monarchy, already threatened by Chartism, slumped further. Gradually, she resumed public life, and by 1877, when she was styled Empress of India, imperial fervour had gripped Great Britain. Between 1867 and 1884 the British electorate was broadened and benefited by Reform Acts, the introduction of the secret ballot, the Royal Commission on Housing and the Representation of the Peoples Act. During her years as queen photography became mainstream, and her subjects were able to collect affordable, fresh and frequently updated images of her and her family in the form of cartes de visite. A dedicated diarist and correspondent, Victoria was an avid collector of photographs herself, and she and Albert often entertained themselves looking through their albums. Both were photographed on their deathbeds. The railway boom of the 1840s also conduced to the monarch’s public profile, as she travelled very frequently on a number of sumptuously appointed trains–including in death, when her body was conveyed from the Isle of Wight to Windsor. At the time she died (to be succeeded by Edward VII) she had 37 surviving great-grandchildren. Owing to the almost inconceivable extent of the British Empire during her reign, more places around the world have been named in honour of Victoria than almost any other historical personage. In Australia these include not only the state of Victoria, the Great Victoria Desert, Lake Alexandrina, the Queen Victoria Building, the Queen Victoria Market, Mount Victoria New South Wales and the Queen Victoria Hospital, but the state of Queensland.

Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant (1845–1902), born Jean-Joseph Constant, was a French painter and etcher. He was born in Paris and studied at the École des Beaux Arts in Toulouse. A trip to Morocco in 1872 strongly influenced his early artistic development, leading to his interests in romantic subjects and orientalism. In the 1880s he made his name as a portrait painter in England, where many aristocratic figures commissioned portraits from him. In 1899 he painted a gigantic portrait of Queen Victoria, depicting her sitting on the Pugin throne in the Lords' Chamber in the Palace of Westminster. It now hangs in the State Dining Room of Windsor Castle. The Royal Collection Trust gives the following account of the work's creation:

This portrait was commissioned by the proprietor of the Illustrated London News. According to a contemporary, Sir Frederick Ponsonby, the Queen only agreed to give a sitting (which was not to last more than 20 minutes) under pressure from the Prince of Wales. To her surprise, the artist ‘never painted at all, but sat with his face between his hands gazing at her during the whole sitting in a most embarrassing way. Of course Benjamin-Constant realized that twenty minutes was ridiculously inadequate for the purpose: he had therefore tried to stamp an impression of her on his brain.’ The portrait was purchased from Sir William Ingram in 1901 and exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1902, after Queen Victoria’s death. King Edward VII did not like the colour of the Garter ribbon in the portrait and sent the artist ‘a whole Garter riband’ so that he could amend it. Constant misunderstood and thought the Order had been conferred on him. When he realized his mistake he ‘absolutely refused to alter the picture’.

Following Victoria's death, reproductions of the portrait were made by various methods. This example is a photogravure - a print made from a photograph of a painting.

Collection: National Portrait Gallery

Purchased 2018

On one level The Companion talks about the most famous and frontline Australians, but on another it tells us about ourselves.

Joanna Gilmour discusses the role of the carte de visite in portraiture’s democratisation, and its harnessing by Victoria, the world’s first media monarch.

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!