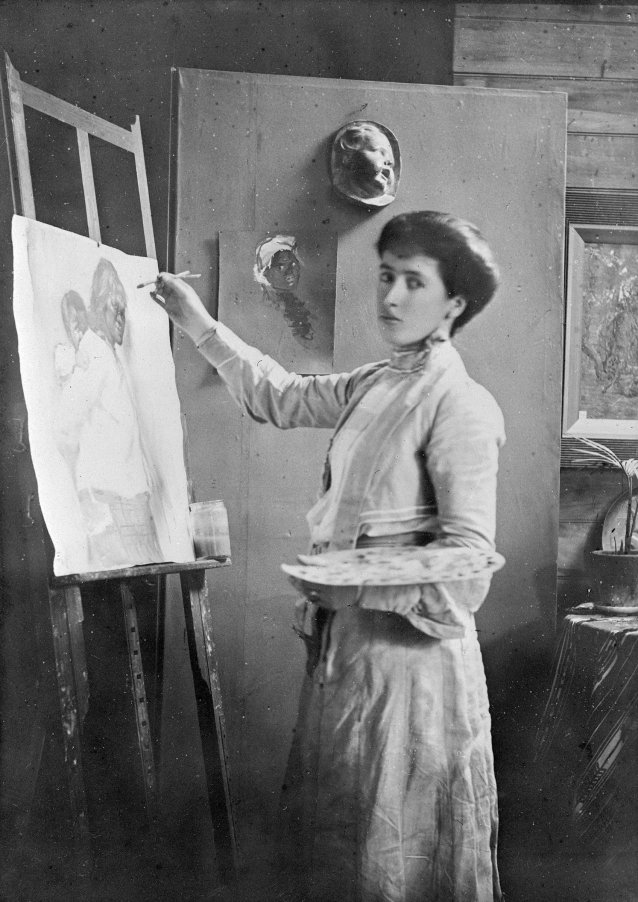

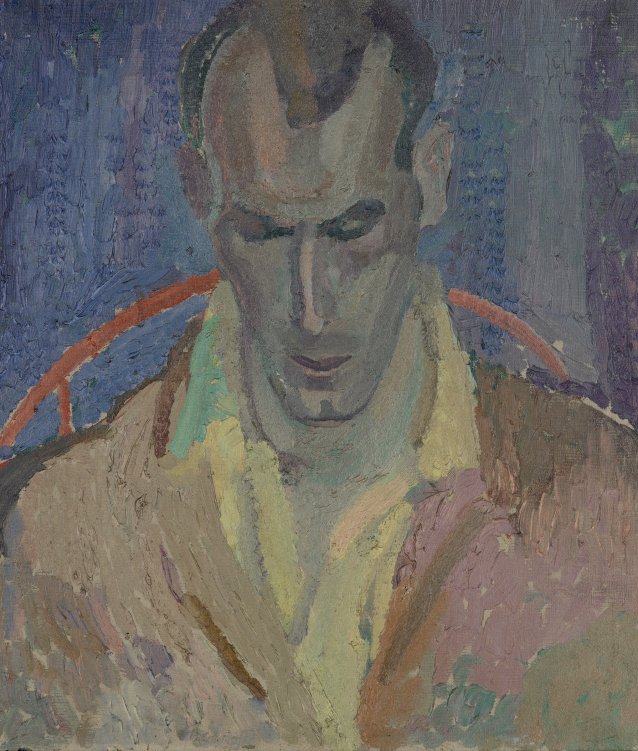

In February this year I had the pleasure of seeing the exhibition, Frances Hodgkins: People, at the New Zealand Portrait Gallery Te Pūkenga Whakaata, in Wellington. Hodgkins is one of New Zealand’s most celebrated painters, with her late still life and landscape paintings underpinning her eminent status in the art history of that country, as well as in Britain. Curated by Pamela Gerrish Nunn, an independent art historian specialising in the work of women artists, the exhibition posited that portraiture is critical to understanding Hodgkins’ life and work. It was a bold and elegant argument; to single out portraiture from an artist’s oeuvre asserts both the existence of an untold story and the authority to tell it. The complexity of Hodgkins’ artistic practice and personality left a deep impression on me, as the intense nature of her personal history materialised from Gerrish Nunn’s deceptively simple chronological arrangement of the exhibition’s 52 portraits.

Loans for the exhibition came primarily from public and private collections in New Zealand’s North Island, and Gerrish Nunn bucked expectations by eschewing some of the works most familiar to New Zealanders. For the curator, the NZPG’s readiness to embrace pieces that would traditionally be classed as figurative painting or character studies signals the young institution’s maturity. ‘I don’t think a portrait gallery can remain content with just that straightforward, literal, classic notion of portraiture’, she told me. ‘It has to reach out and keep testing boundaries.’

For her part, NZPG Director Jaenine Parkinson was forthright about the significance of the exhibition for the institution: ‘Hodgkins is one of New Zealand’s most prominent historic artists, and we believe her work being shown here indicates that the NZPG is on equal standing with the best cultural institutions of this country’s national and public life.’ According to Parkinson, local visitors engaged warmly with the unfamiliar story of a familiar, national artist-hero, and international visitors were pleased to see in the works ‘a vivid face of New Zealand’. From my perspective, the face on show was that of a surprising, complicated and determined artist made visible through the people she painted.