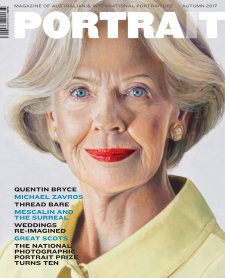

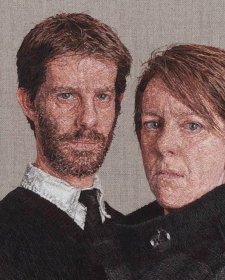

In many respects, wedding photography can be considered a form of portraiture. Weddings are about people, after all — the couple, their family and friends — and creating portraits of those people is an intrinsic part of documenting the event.

O’Day agrees: ‘Many of my [wedding] images, when they’re considered on their own, are portraits that I’ve put a lot of effort into.’ Often that effort aims to push the boundaries; to show people something they haven’t seen before.

‘A picture that, if you saw it on a wall by itself — and if they weren’t dressed in wedding clothes — it could be something you might see in a portrait prize … just a really interesting, contemporary image.’

The recent, seismic shift in style and standard of wedding photography, typified by the likes of O’Day and Tunney, has been astounding; it has radically changed our ideas and perceptions of what is possible, and indeed expected, of modern wedding photographers.

‘There’s been so much progression’, O’Day muses. ‘The benchmark is so high now; it’s amazing. You can’t afford to relax or be complacent … but I like that because it forces you to make sure you’re always pushing forward, to be as good as you possibly can.’

Looking to the future, both photographers have noticed a resurgence of interest in cinematography and film, and predict the momentum will continue to build in coming years. ‘People are doing some amazing stuff with video’, says Tunney. O’Day agrees: ‘It was off the grid for so long … Nowadays though, there’s often someone doing film at the weddings I’m shooting – and they’re doing it really well, too.’

O’Day doesn’t hold any fears for the future of stills photography, though. ‘Moving forward, I think there’s going to be an even-greater emphasis on photojournalism and reportage styles of shooting. I don’t think good documentary’s ever going to go out of fashion – I think that’s always going to be the one consistent aspect of wedding photography. If people can do that well, they’ll be able to stay in business.’

‘Good documentary’ is instructive, if understated. In the case of O’Day and Tunney, it means an innovative, left-of-centre approach to a familiar scene that consistently sets them apart from other photographers. They also have an enviable ability to create pictures that not only appeal to their clients, but also resonate with complete strangers who have no emotional attachment whatsoever to the images. And that’s almost always the calling card of exceptional photography, regardless

of the genre.

![Untitled [library], 2013 © Kelly Tunney Untitled [library], 2013 © Kelly Tunney](/files/4/c/f/c/i9948-wd.jpg)

![Untitled [church], 2014 © Dan O’Day Untitled [church], 2014 © Dan O’Day](/files/4/4/2/f/i9945-wd.jpg)

![Untitled [proof sheet], 2014 © Dan O’Day Untitled [proof sheet], 2014 © Dan O’Day](/files/7/3/9/5/i9947-wd.jpg)

![Untitled [party], 2015 © Dan O’Day Untitled [party], 2015 © Dan O’Day](/files/b/5/4/d/i9946-wd.jpg)

![Untitled [alley cats], 2011 © Kelly Tunney Untitled [alley cats], 2011 © Kelly Tunney](/files/f/9/f/5/i9949-wd.jpg)

![Untitled [Post-it notes], 2013 Untitled [Post-it notes], 2013](/files/9/8/d/6/i9951-wd.jpg)

![Untitled [Skyspace NGA], 2015 © Dan O’Day Untitled [Skyspace NGA], 2015 © Dan O’Day](/files/f/2/d/0/i9943-wd.jpg)

![Untitled [xray], 2015 © Dan O’Day Untitled [xray], 2015 © Dan O’Day](/files/6/6/5/4/i9944-wd.jpg)