The New Zealand Portrait Gallery has just seen another very popular Adam Portraiture Award come to its successful conclusion. This biennial event has become a fixture on Wellington’s visual culture calendar, attracting huge visitor numbers and enthusiastic audience participation. Established in 2002 and named for its patrons, Denis and Verna Adam, the award is a successor to the first ever national portrait award, which was administered in 2000 by the New Zealand Portrait Gallery.

The Gallery itself began only towards the end of 1991, a result of agitation for such a national institution begun in 1988 by Bill Williams, Judy Williams and Sir John Marshall; it was established in its present home on Wellington’s waterfront only in 2010. From the outset, the institution favoured the idea of demonstrating and promoting the Gallery’s raison d’etre with a national competition, history having shown the merit of this concept across the Tasman in the form of Australia’s Archibald Prize, and across the globe in the London National Portrait Gallery’s BP Portrait Award. The influence of the latter prize on the Adam Award was reflected in the choice of then director of the British National Portrait Gallery, Charles Saumarez Smith, as the prize’s inaugural judge.

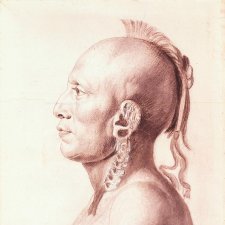

Of course, there have been and continue to be other important art awards in New Zealand, from the pioneering National Bank Art Award instituted in 1958, which has grown to include an invitation to portraitists, to all-round art awards such as the Walters Prize, and more than one annual competition specifically recognising drawing (the Cranleigh Barton Award; the Parkin Prize). Although Auckland hosted the Nola Holmwood Portrait Award from 1973 to 2002, the 1990s provided few significant opportunities for portraitists throughout the country to participate in a collective endeavour to personify ‘New Zealandness’. As a consequence, there remained a clear desire for portraiture that showcased the country’s heritage and character, bore witness to its heterogeneity (as well as its specificity), and spoke to New Zealanders’ famed embrace of egalitarianism.

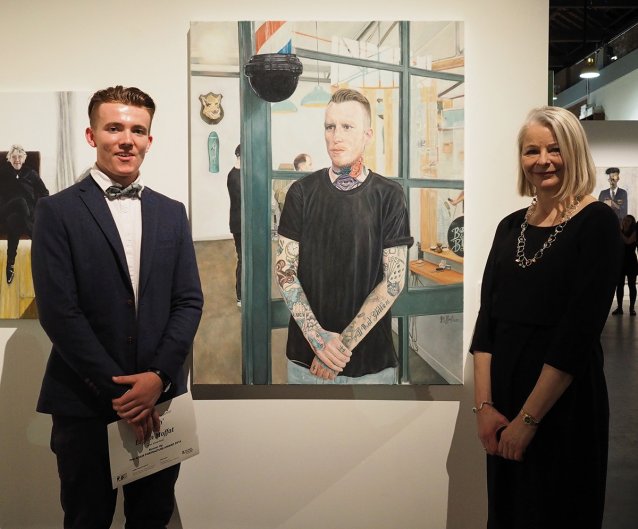

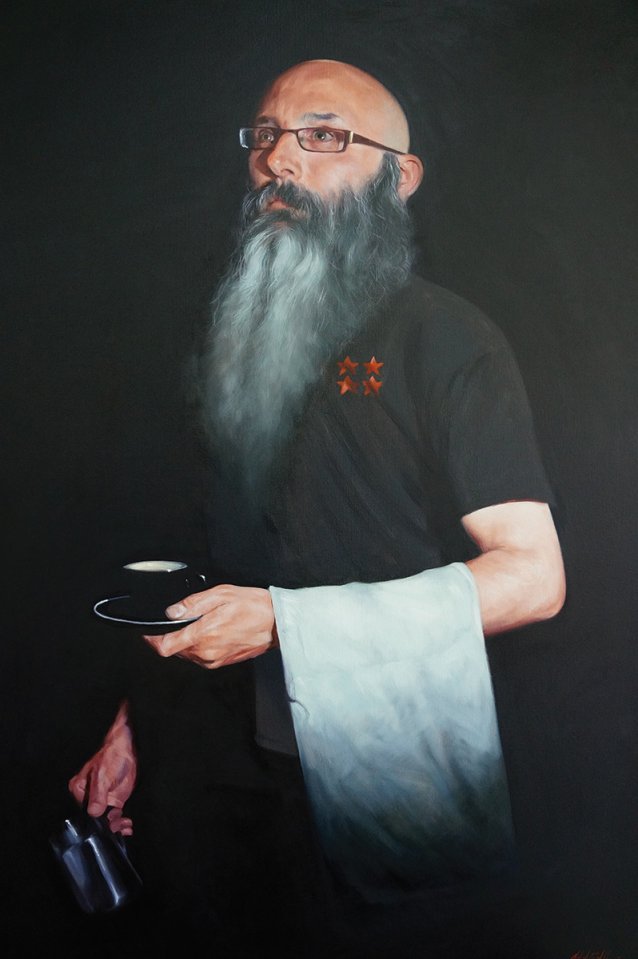

The result of this pursuit – the Adam Award – celebrates portraits that represent NZPG’s own kaupapa (purpose, objective). While the winner looks forward to a $20,000 purse, the award is about much more than just prize money. And although it includes the ‘rich and famous’, it by no means favours the elite; in fact, the Adam provides a platform for portraits that represent a cross-section of New Zealand society. The award recognises portraiture as a pictorial record for future generations, and thus a historical and social taonga (treasure) as much as an aesthetic one.