Try it for yourself: an exegesis of the contrast in intention, technique and impact between Alexia Sinclair’s meticulously constructed self portrait as Napoléon, and Jon Van-Den-Broeke’s startlingly detailed snap of his elderly mother and aunt, Nell and Dode.

Multiply, exponentially, the disparities between these works, and you will have some idea of the challenge of selecting photographs for exhibition in the National Photographic Portrait Prize – to say nothing of expounding on the selection. The Prize is a mixed bag, all right; a show notable, if for nothing else, for its catholicity.

It has never been easier to take, or concoct, an arresting photograph. The corollaries are that people have never been warier of the use of their images, on one hand, or keener for them to be seen – whatever they’re doing in them – on the other. One image was of a young couple at an early, but not very early, level of lovemaking. ‘It was as if I wasn’t even there’, the photographer averred. Looking at this picture with some private amusement, I reflected that a photographer can manipulate the way a photograph looks, and its subjects might have some say in how and where it’s displayed, but once a photograph is exhibited, no one can control what any individual thinks about as he or she looks at it. The awakening of associations and the stimulus of memories are inherent functions of photographs. But multiply proliferating recollections and responses by well over a thousand, and you have an idea of the task confronting the judges of the 2011 National Photographic Portrait Prize competition. As different as we four are, we judges are human, with our own histories and involuntary reactions. We can’t select the best five percent of a huge number of photographs by applying a set of independent measures. We can’t even guarantee that the ones we pick are the best. One or two photographs, frankly, were picked because the sitters were so beautiful; at least one got through simply because it made all the judges laugh. Portraiture is personal.

Rarely have I derived as much enjoyment from doing something terribly difficult as I did as a member of the judging panel. One of the first questions I was asked on the opening day was whether the winning portrait – Jacqueline Mitelman’s Miss Alesandra, with her air of hauteur and wounded, wary eyes – was a unanimous choice. Surprised at being unprepared for this question, I stammered that it was unanimous in so far as there was strong agreement amongst the judges that it was a worthy winner – but that consensus had been reached after some hours of discussion, after a great deal of pacing and peering around the locked, unpopulated gallery space, and after each judge had noted his or her ‘top five’ on a series of voting cards produced especially for the purpose.

Greg Weight devised an intriguing backdrop – two-thirds lushly-painted canvas, one-third stretchers and roller door – before he embarked on many photographs of his friends, Jiawei, Lan and Xini and their dog Billy. In just one of the shots he accumulated, he arrived at a superb family tableau. Jiawei, standing before his own self portrait as the patient court painter of old, wears the smug expression of a proud paterfamilias. Wan Lan exudes patience and resilience. Their daughter Xini, a modern Sydney girl, looks something like a jade princess with her eyes diffidently downcast. While the painted Billy dozes, the gaze of the photographed Billy, his feathery fur fanned on the floorboards, locks the elements of the picture together.

The photograph of Jiawei Shen’s family is a masterpiece of colour and composition, realised by a practitioner of long experience who had photographed his subjects before. By contrast, Dean McCartney had only a second in which to capture his newborn son, James, roaring into life. A photograph of superb drama, for me it conjured up the doom of Macbeth, killed by Macduff, who was ‘from his mother’s womb untimely ripp’d’.

Similarly expressive of eternal truths is Gibson Nolte’s Harbour road, a photograph of Hayley McElhinney and her newborn daughter Betty, her toe sunk into the softness of her mother’s arm. The grainy black and white photograph evokes the reportage shots David Moore took in Redfern and Surry Hills in the late 1940s. So resolved is the photograph as a work of art, so primal the expression of its subject, that I found it hard to believe that she exists in any alternative, real form. I found it difficult to credit Nolte’s statement that most of the shots he took that afternoon were ‘light and playful’. I was even more surprised to learn independently that the monumental mother portrayed in Harbour Road is an actor, soon to appear on the international stage alongside Cate Blanchett, Hugo Weaving and John Bell in Uncle Vanya.

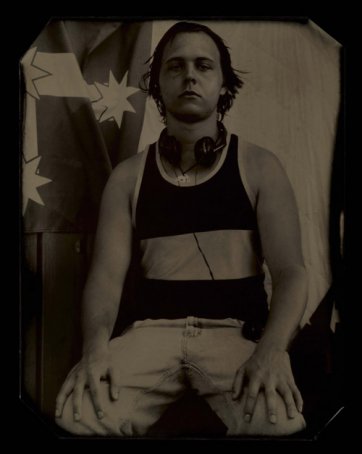

Nolte’s photograph of Hayley and Betty was not set up to evoke the mood that it does. By contrast, CJ Taylor played very deliberately with signifiers of time, class and place as he constructed his tiny tintype Robert. I was fascinated by the impressions of the sitter that succeeded each other, rapidly, as this photograph scrolled as a digital image – and the alternative perspectives that pinballed around my brain as I viewed the finished work. Robert looks like a nineteenth-century miner – an impression reinforced, or created, by the Eureka flag beside him. He could be a bushranger or convict – a suggestion supported by his greasy hair and the tintype medium. He looks like a fighter, with the remnants of a black eye; he sits in the attitude of a footballer in a team photograph. The flag may be the appropriated standard of a bikie gang or nationalist collective. Yet the headphones, emphasising the deliberate anachronism of the portrait object, provide a way in to the contradiction confirmed in the artist’s statement - which reveals that Robert is a postdoctorate student on a scholarship. Robert, like several others in the exhibition, reminds us that the story displayed alongside a portrait can radically, and irrevocably, alter the way in which it is read. It reminds us, in other words, that we all bring preconceptions, fears and prejudices to the study of faces.

In a human life, what is photographed contributes significantly to the shape of what is remembered. In a time when huge numbers of people are never without a camera, more people than ever are taking photographs to remember a situation, to capture an extraordinary moment, commemorate a characteristic one, or provide tangible expression of a fantasy. In fact, in the rush to capture a moment, it may be that we forget to consummate it: an eminent Australian told me recently that when she moves through a group, catches an eye and moves forward in greeting, she’s frequently met with a brandished camera, instead of than the handshake she’s initiated. The more we stumble around in the excess of real life the more infatuated we become with the order attainable in the photograph. The greater the din around us, the more attracted we are to the quietude of the photograph. The more we age, and events betray us, the more reassured we are by the unchanging nature of the photograph.

Most people in the National Photographic Portrait Prize are pictured expressionless or with a faintly wry look. Looking into the strong face of John Withers we may experience a feeling of personal humility, grounding and grave. By contrast, in the gallery context, to turn to Van-Den-Broeke’s jubilant old sisters, their powdery faces tilted together, is to experience a surge of joyfulness that’s almost shocking.

There is no reason to expect that the photographs entered in the National Photographic Portrait Prize will get better with every passing year. Perhaps we’ll see the day when every shot is in perfect focus; but at the expense, perhaps, of the amateur snaps that seem to tell us something important about the human condition. Maybe there’ll come a time when every image is digitally manipulated, showing us what we would all look like with bigger eyes, pointed ears, a symmetrical face or flawless skin; but what would be the point of such an array of pictures? Someone might curate an exhibition every shot of which is occluded in some way, the face glimpsed through lace or foliage, made out through a foggy window, peering from shadow, bounced endlessly between a series of mirrors; but who’d have the patience to search out what is, ultimately, no more and no less than another person in every frame? The human face can be enhanced to the point of unrecognisability, and can be hidden to the point of unrecognisability – but between these extremes there falls no more and no less than the human face.