When Socrates said that the unconsidered life is not worth living, he was making a statement that continues to have direct relevance to the work of national portrait galleries. Portrait galleries cause us to reflect on our own lives and to consider the lives of others.

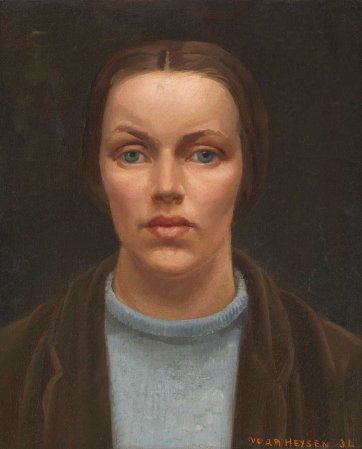

Socrates is sometimes translated as having said the unexamined life is not worth living. In the world of portraiture, self portraits provide the most conspicuous examples and obvious visual equivalents of this process of self-examination. Of course, scrutinising a face is not the same thing as examining a life. Many self portraits (particularly those of student artist) have been merely exercises in seeing and skill-raising. Yet there are self portraits in which the artist’s intention goes well beyond the physiognomic recording.

Salvator Rosa’s self portrait of 1645 is explicitly philosophical. The artist depicts himself holding a placard that reads (in translation) ‘Do not speak unless your words be better than silence’. It is a warning I often take to heart. The National Portrait Gallery is full of self portrait revelations. George Lambert’s Self portrait with gladioli now seems rather stagy and forced, but the artist’s intention was indeed to examine his own life. Painted in 1922 shortly after his return from two decades in London, Lambert was both celebrating his public place as Australia’s most lauded artist whilst, at the same time, letting us know that living up to his reputation was, well, all a bit of a tiresome pose.

Nora Heysen, whose 1934 self portrait hangs opposite in the National Portrait Gallery is much less affected. When this portrait entered the collection, Nora Heysen told me that it was the first painting she embarked on after she arrived in London to study. Her first response to a new setting was always to start with what she knew best – herself. The urge to examine one’s place in the world is not an unusual motivation for the painting of a self portrait. As well as examples of selfreflection national portrait galleries invite us to consider the lives of others.

The admiration of lives has always been a motivation for portrait galleries. Or, perhaps, it would be more correct to say the admiration of achievements, because, deep down we don’t really know much about the lives of other people – their inner thoughts, desires, anxieties, elations, insecurities. In the realm of considered lives, public and private are different places.

Jessie Street, whose 1929 portrait was given recently to the National Portrait Gallery, was a person for whom it is impossible not to feel a great sense of admiration. In the National Portrait Gallery context, the moment in time when this portrait was painted is a pointer to her role in public life – 1929 was the year she formed the United Associations of Women, an organisation with an explicitly feminist agenda. A committed Australian nationalist, a campaigner of huge energy, a supportive wife and a role-model mother – the life of such a person inevitably calls on us to examine our own contribution to the world and our own commitment to public life. Her avowed motivation was to leave the world a better place for her grandchildren.

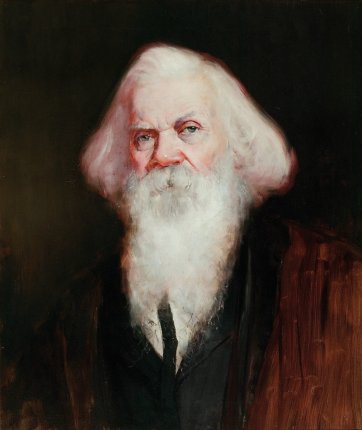

In public life, triumph over adversity is everywhere to be seen in the National Portrait Gallery. Henry Parkes, probably the most significant Australian statesman of the nineteenth century, bounced back from not one but multiple bankruptcies.

Parkes had a distinctive face. It was a face that was painted numerous times, never better than in Tom Roberts’s 1892 portrayal. A face is a face, and even if it comes to stand for a person in the context of a National Portrait Gallery to what extent can a portrait represent a life? ‘Who I am is constantly shifting’. You might recognise that as a line from the actor’s voiceover in David Rosetzky’s video portrait of Cate Blanchett in the National Portrait Gallery collection.

‘A person can be completely contradictory’ – another line from the same piece. A portrait indeed can represent contradiction. Sometimes different aspects of a personality seem to be co-existing with each other across the visage. We can see that for example in Robert Hannaford’s portraits of Lowitja O’Donohue and Robert Dessaix.

In terms of portraying a life, there are two things that a portrait is unable to do. Firstly, a portrait can only represent a moment in a life, not a totality. Secondly, a portrait can only represent an outward appearance – it can tell us nothing about intentions or about good and evil.

To look at the first of these – a portrait confirms the presence of a person in the world. That fact alone is visual evidence of a life. Yet we have to infer continuity. Portraits are momentary. They are often at their best when they capture the immediacy of a moment – or the weaving together a short sequence of moments. Even a portrait that is painted over a series of separated sittings really only represents a short passage in the totality of the life of a person. On the other hand, portraits can attempt a summation.

Roberts’s portrait of Parkes was originally conceived as one part of a portrait triptych entitled Law, State and Church. So in the painter’s eyes the life of Parkes – he was to die four years later – was seen as synonymous with his dominant role in Australian political life; he has grown up with and been a part of relatively new political formations. Or to put it another way Parkes is here the personification of an institution. Roberts painted Parkes in 1892, the same year that Parkes’s Fifty Years in the Making of Australian History, was published. That book was a much more complete examination of a life than a portraitist could possibly achieve. In his apologia Parkes says: ‘Whatever my work may amount to, it cannot be made more by words from me or from too tolerant friends, and it cannot be made less by the comments of adversaries. It must stand or be swept away according to the nature of its substance’. Further, tackling the subject of who is best able to judge a life, Parkes has this to say: ‘I hold the opinion that any man of a fair average degree of commonsense, can judge more accurately of his own work in life, where it stands untainted by sinister bias, than any observer can judge of it’. When we think of the ideal of the considered life our ethics are front and centre. In a portrait, ethical dimensions have to be inferred or described in an accompanying text. These things cannot be represented.

Although we have striven at the National Portrait Gallery to create a modern institution, there are some ideas that link us to our nineteenth century predecessors. In the Victorian age a National Portrait Gallery was a place where example was important. We no longer consider the Gallery to be solely a place devoted to figures who we should ‘look up to’. Nonetheless we seek some human connection to the people represented on the walls here. Sometimes that connection is admiration, pride; sometimes it is empathy, compassion, projection, sometimes we simply look upon people as exemplifying historical circumstance.

There are many ways to consider the lives of others. Ideally, though, visitors to the Gallery will not only consider the lives of other people - across history and in our own time - but be led to reflect on their own lives. That is really the core of the unique experience offered by the National Portrait Gallery.