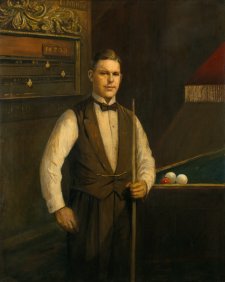

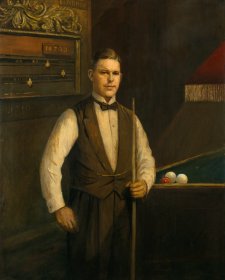

Robert Hannaford has completed around 400 portraits over the span of his career. Many of his portraits are commissions; he has painted Australia's leading politicians, surgeons, sporting heroes, academics, judges and performers.

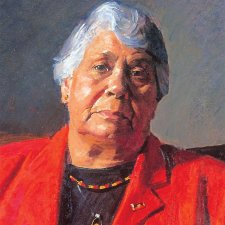

The National Portrait Gallery has two of these in the permanent collection, a portrait of opera diva Dame Joan Sutherland OM AC DBE (c.1977) and the Gallery's own recent commission, a painting of Indigenous rights campaigner, Lowitja O'Donoghue AC OBE (2006). Hannaford also paints friends, family and people he finds interesting and in the National Portrait Gallery's collection is one such fine example, a painting of author Robert Dessaix (1995). At the beginning of his career, Robert Hannaford (b. 1944) worked for three years as a political cartoonist for the South Australian newspaper, The Advertiser. The experience helped develop his approach to portraiture, teaching him, as he stated 'to form a basic likeness in just a few lines'. Hannaford paints from life, never from photographs and a subject is required to attend multiple sittings. One of the clear advantages of painting from life, Hannaford has elaborated, is 'to get the person in a position, light and angle where they most look like themselves'. Although Hannaford's style is frequently described as Realist, it is obvious his intention with portrait painting extends beyond the mimetic function of the genre. As he continued, 'I try to capture as much about a person's character as I can'. The experience of painting from life and the interaction between artist and subject is reflected in Hannaford's portraits. There is a consciousness of passing time and shifting light. This is strongly felt through the immediacy of the effect of the brush on canvas, creating energised and organic painted surfaces. There is also a sense of occasion to Hannaford's portraits. Regularly a subject is depicted in a formal pose, often seated with upright posture and hands placed neatly in front. The sitter stares out of the picture, directly at the viewer. Hannaford creates a presence for the subject that is rather respectful and dignified, as the portrait of Dame Joan Sutherland demonstrates. This work is a faithful rendition of the original commission from the Elizabeth Theatre Trust. The sittings occurred over a two week period at Potts Point, Sydney, while Dame Joan was performing at the Sydney Opera House. Hannaford was struck by her dedication to her work, a professionalism for which Dame Joan is renowned. The artist recalled she would not sit on the days of performances, while during portrait sittings, her husband the conductor Richard Bonynge, would provide tapes for her to listen to, enabling her to practise vocal exercises. Hannaford remembers finding Dame Joan had a beautiful neck and this observation has translated in to the portrait, in which her neck is a feature, her creamy skin emphasised by her black dress with a deep V neck line and fiery red hair. Intentionally, or not, Hannaford's work does continue in the Australian tradition of formal portrait painting. He is frequently likened to Australia's other eminent portrait artists, Sir William Dargie and Sir Ivor Hele. Hele, a fellow South Australian, was a strong influence on Hannaford, who was impressed by his 'vast knowledge of light, form and anatomy'. As a young, untrained artist, Hannaford recalled he would 'visit him one or a twice a year. His help was invaluable for me'. Hele would look at his paintings and drawings point out weaknesses and really, Hannaford believes, teach 'the representational skill using eyes to see and then represent this on paper'. This attention to detail has had an enduring impact and Hannaford's paintings are meticulously worked over, with no part of the surface of the canvas appearing untouched, or unfinished. The artists also had a shared interest in anatomy. Hannaford has studied both human and animal anatomy, stating 'I love anatomy in its own right, especially comparative anatomy'. He is particularly interested in the way bones and muscles have developed in accordance to environmental conditions. His figurative paintings demonstrate a solid understanding of bone structure, musculature and skin tension. Hannaford's works are clearly structured and his bodies are neat, contained shapes. This approach is softened and balanced by building up the work tonally, with layer upon layer of evenly weighted painted brush strokes. He has a strong sense of the subtleties of light and shade. He draws the viewers' attention to the contours of the human face, the soft skin of an earlobe and the glint of light on a fingernail. The portrait of Lowitja O'Donoghue is a fine example of these aspects of his practice. Hannaford told the abc News last year: When she came to the studio I took her into the studio with a south light, and I knew within minutes it was going to be wonderful - the way she happened to be wearing a red suit with a black jumper and she just looked fantastic in that light I've got in that studio, so I was excited from the start. O'Donoghue is a Yankunjatjara woman, who from the age of two was raised in a mission home at Quorn in South Australia's Flinders Ranges. As a young adult she joined the Aboriginal Advancement League and fought for the right to train as a nurse at the Royal Adelaide Hospital. After a period of nursing in India, O'Donoghue returned to Australia to engage in a life long commitment to improving Indigenous health, welfare and human rights. O'Donoghue has stated she is driven by a desire that all Australians 'accept that Aboriginal people have rights and to appreciate that in fact we have a living culture and one that they can be part of in terms of making'. She has chaired the National Aboriginal Conference (1977), the Aboriginal Development Commission (1989-1990) and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Commission (1990-1996). In acknowledgement of her work, O'Donoghue has received multiple accolades, including five honorary doctorates and being named Australian of the Year in 1984. In Hannaford's portrait, there is a strength and warmth to O'Donoghue. She sits confidently in her red suit, wearing jewelry that bears the Aboriginal flag. The artist also observed 'a vast understanding and sympathy in her face, a sadness'. The painting process, held over six to eight sittings, was as Hannaford remembers 'a fascinating experience' and the two have become good friends. The commission took place while Hannaford was undergoing chemotherapy for throat cancer. The cancer was caused most likely from Hannaford's habit of placing his brushes, covered in toxic paint, in his mouth. The experience resulted in the arresting and mortality conscious Self portrait with feeding tube, entered in this year's Archibald Prize. The self portrait had been re-worked over a period of about ten years. The process has been captured in Ian Lloyd's photograph of Hannaford, to be included in the National Portrait Gallery's forthcoming exhibition Studio: Australian painters photographed by R. Ian Lloyd.