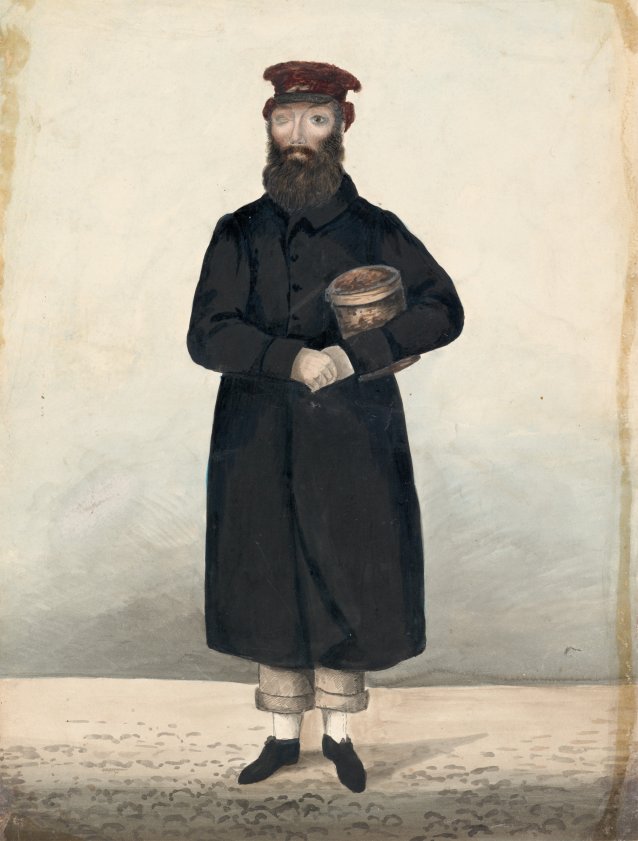

For 40 years James Guidney was a familiar figure in the streets of Birmingham. Dressed in a peaked cap, a red military jacket and with a long beard, turning white with age, he sold medicated toffees with the cry: ‘Good for cough or cold, cough or cold’. His celebrity was such that his real name was eventually almost forgotten, and he became simply ‘Jemmy the Rock Man’. His portrait was taken on more than one occasion: the Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery holds a watercolour and three oil paintings, as well as a silver-plated relief profile figurine. The Birmingham folk life collections also preserve the japanned tin canister from which he sold his sweets. Jemmy’s story survives not only through these images and objects, but through his own words, or those of a ghost writer: Some particulars of the life and adventures of James Guidney … went through at least four editions.

Born in Norwich in 1782, Guidney had a dual education: working with 500 other boys at a ‘spinning school’, and on alternate days attending a charity school, for lessons in reading and arithmetic. After five years at the charity school he graduated with a modicum of literacy and numeracy, and the parting gift of sixpence and a Bible. He then spent a year in casual work — running errands, selling milk and apples — before enlisting as a drummer boy with the 48th Northamptonshire Regiment in 1797.

Much of his autobiography consists of an account of the activities of his regiment, as it moved between England and the Mediterranean in the course of the Napoleonic Wars. However, in between the recitation of troop movements and travelogue descriptions, Guidney’s book also contains flashes of more personal and colourful incidents. On Malta he lost an eye from ophthalmia but survived an earthquake. At Gibraltar, he saw a curious fish, ‘no doubt one of those animals that have been called Mermaids, several of whom have unquestionably been found,’ and when stationed on Paragil, off Morocco, had a narrow escape when armed Africans captured 10 of his comrades.

Most curious of all was the vision while on Malta.

... one morning in May, 1802 ... a lamb suddenly appeared before him on the high road ... After walking beside him for some distance ... it turned round and stood in his way, and, assuming the form of a man, addressed him by name, commanding him for the future to wear a beard! He then put his hand on his head and face, to satisfy himself that he was not deceived, and distinctly feeling the flesh of a man, a cold perspiration came over him. It afterwards re-assumed the shape of a lamb.

At the end of the wars, with an army pension of one shilling per day, Guidney returned to his native Norwich, where he took a position as footman and butler. ‘The quiet life of service (was) not congenial to his roving habits,’ however, and he took up the trade of a travelling hawker, selling rhubarb, little books and fancy articles ‘through most of the Counties of England.’ During a visit to London in 1824, he was charged under the new Vagrancy Act for singing in the street, and was committed to Cold Bath Fields Prison for three months. Here his beard was shaved, for the only time since his adventure with the lamb.

On his release, Guidney originally returned to hawking, but his regrown beard now proved an asset; he was employed by Col. Durant of Tong Castle, Shropshire, as a Picturesque living garden ornament, ‘the Hermit of Tong’, before making his way to Birmingham. Here he finally settled down, marrying Elizabeth Pitt, daughter of a locksmith and bell-hanger, in 1828. For the next four decades he walked the city selling his ‘composition’, lead pencils and, later, copies of his biography, ‘from nine o’clock in the morning ‘til eight or nine at night.’ He also offered his musical services: Some particulars… concludes: ‘Having had very considerable experience as a drummer, James Guidney will be happy to attend any public parties of pleasure, and may be found at his residence 18 Communications Row, Birmingham.’ It was in this house that Jemmy the Rock Man died in 1866, at the age of 84.

Collection: Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, presented by C. Docker, 1956