During this early period Sundaram’s practice revolved around historical figurative painting, later experimenting with diverse and semiotically charged mediums. Inevitably this led into more dimensional works, which incorporated objects carefully chosen and arranged to engage the viewer with specific concepts. Recent work has incorporated large-scale photographs, installations and videos of constructions created from masses of rubbish. This TRASH series confronts the audience with the waste it generates and urges discourse to resolve the social and environmental impacts of our consumption. Sundaram now lives in New Delhi, and has exhibited widely in India, Europe and the United States.

Family romance:

The Devil's dilemma and the Re-take of Amrita

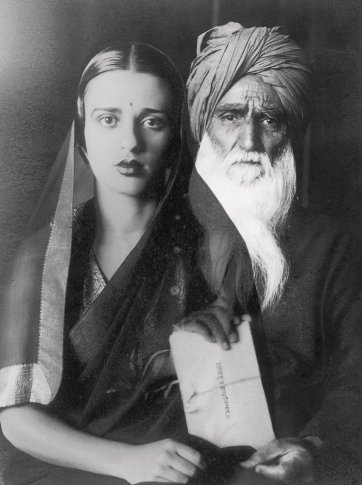

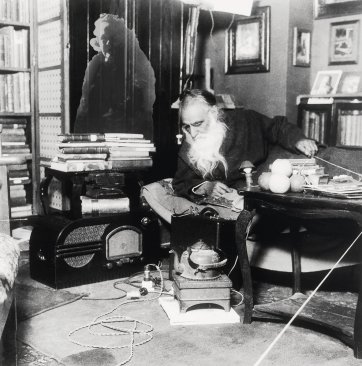

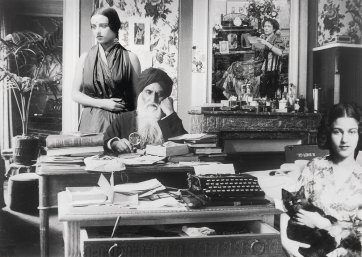

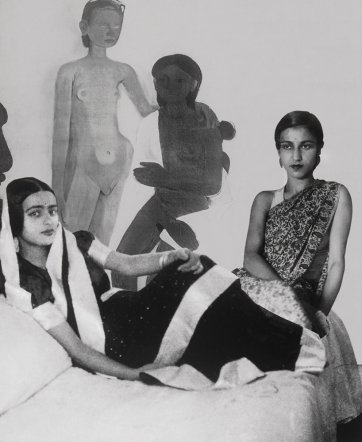

‘Every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way’ Leo Tolstoy famously wrote in Anna Karenina (1877), his faithful observance of beauty, brilliance and tragedy in upper-class St Petersburg, which psychologically foregrounds the modern family. Such themes linger through the silent black and white photographs from Re-take of Amrita 2001–02 by the artist Vivan Sundaram, far from Russia, and removed by centuries, mixing fiction, fact and fantasy to reconstruct the ‘history’ of a glittering and elite Sikh family against the backdrop of colonial and postcolonial India. Umrao Singh Sher-Gil (1870–1954) – family patriarch, amateur photographer and follower of visionaries, Tolstoy and Gandhi – appears in the photographs, aged in some, virile in others, while his wife, Marie Antoinette, and two daughters, Amrita and Indira, are vibrant and beautiful in the family photographs, many of which were taken by him. The images interweave complex portraits within portraits of the genealogy of a cosmopolitan family. Vivan Sundaram’s appearance as a small child in one of the photographs, seated on his grandfather’s lap with a Voigtländer camera and surrounded by members of his family at different ages, tells another story. The image belies an adult Sundaram’s intent, on the one hand, to come to terms with the burden of legacy and a world of which he is unaware except through memory, photographs and paintings, and on the other, a design in retelling that truth through his own eyes. The game becomes as tragic and timely as any epic.

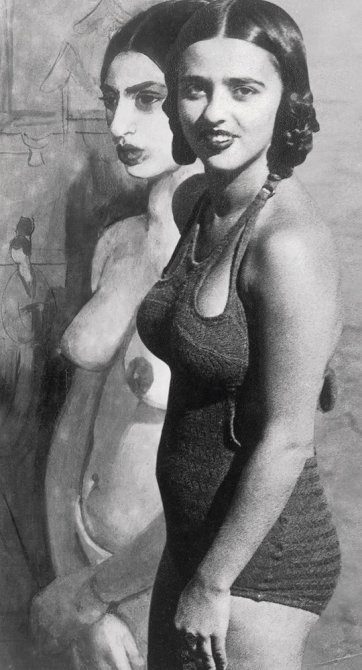

At the centre of the series, or what Sundaram calls a ‘photo-dream-love-play’, is Amrita Sher-Gil, India’s most celebrated modern artist, daughter of Umrao Singh Sher-Gil and his wife, Marie Antoinette, an opera singer who later committed suicide due in part to her daughter’s untimely death.1 Amrita Sher-Gil, who died in 1941, at age twenty-eight, has become part of a legend of a bright star gone too soon, wilful and independent artist dead before India’s Independence. Her legacy and her paintings, many of which hang as a bequest in the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi, are as much about the story of Indian painting and modern art as about specific family history. Less well known is Amrita’s sister, Indira, who shaped much of the family history for her son, Vivan. Umrao’s photographs and Amrita’s oil paintings become the foundation on which Sundaram blends fact and fiction through a careful reconstruction of narratives. Like a precise surgeon, the thin tissues of manipulation are rendered invisible with the aid of digital technology until the viewer is left to search for the lines, the sutures, the truth that underlies the story in a family not their own, and which, through archetypes, their own may possibly be seen.

The ‘re-take’ in the title of the series is not just in reference to photography and film (a film on Amrita by Kumar Shahani in 1985 was in production but never realised), but a possession both in terms of owning a legacy as much as a possession by a spirit. The suggestions of a haunting are apparent: the ghostly presence of Marie Antoinette looms in one image behind the chaise of Umrao Sher-Gil as he silently lays lost in thought. At the same time, photographic portraits of Amrita and Indira are juxtaposed against actual paintings by Amrita creating a distinction between portrait, self portrait, photograph and the elusive real subject. As such Sundaram captures the twin desire and fear of early photography: the memento mori as the remembrance of death and the loss of soul that superstitious people believed of the photograph. The suggestion of shadow selves, or the double, seen throughout this series, is what psychoanalyst Otto Rank equated with death. He writes of the double, ‘… at the beginning was the soul of a living man and that which little by little became the soul of death … the Double had evolved from a guardian angel to an angel of Death’.2

This drive to resurrect history and question fact and fiction, mortality and immortality, memory and reconstruction underlies Re-take of Amrita as does the importance of the photographic medium. The latter may undercut any of the upper-class and bohemian advantages the family represents through the face; as Christopher Pinney points out, the focus on the face was the privilege of the modern Indian state as photography enabled ‘every citizen’ a face, which before had been the right of only gods and kings.3 As such the status of the Sher-Gil family is marked not only by the impossible luxury of decor and dress (or the equally impossible photographs of nudity), but also ordinariness. Sundaram also nods to the radical experiments of the Surrealists, who were prominent during the time of Amrita’s stay in Paris (and whom she ignored), but shows signs of fulfilment in the use of unconscious desire to reshape everyday life which Sundaram achieves through manipulation of a conventional and intimate family album in the form of photomontage. The process of representation itself is at stake, from the history of photography and his grandfather’s pioneering use of autochromes and experiments with the stereoscopic camera under colonialism to Sundaram’s use of computers and Photoshop in a democratic and post-liberalized India ready to reflect on its past and recreate family legacy through new technology, or a fictional version of truth staged and sold at the millennium.

Rakhee Balaram

Visiting Professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi

1 Vivan Sundaram, ‘Illumination and Death’, 2001, reprinted in Re-take of Amrita, (exhibition catalogue), New York: Sepia International and The Alkazi Collection, 2006, p. 9.

2 Otto Rank, Don Juan et le double (1914–1922), Paris: Editions Payot, 1973, pp. 111–12.

3 Christopher Pinney, The coming of photography to India, London: The British Library, 2008, p. 137.