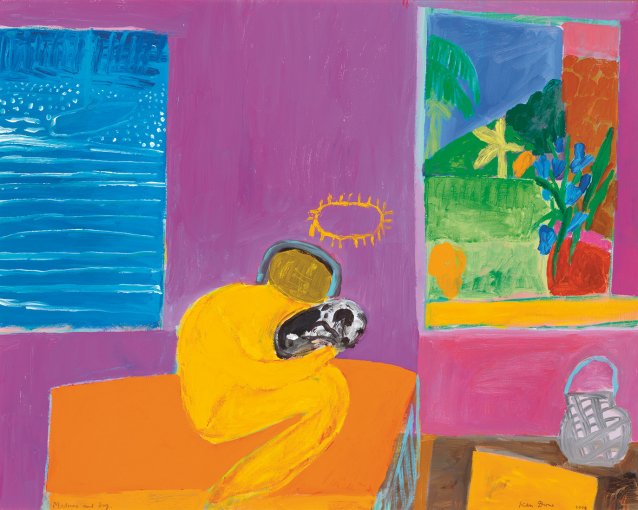

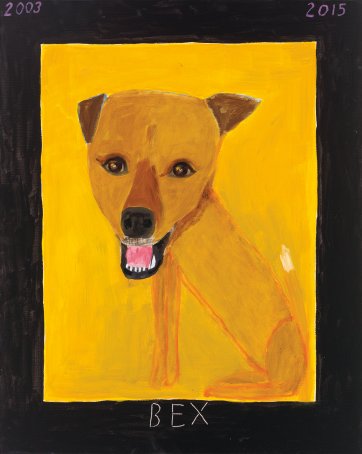

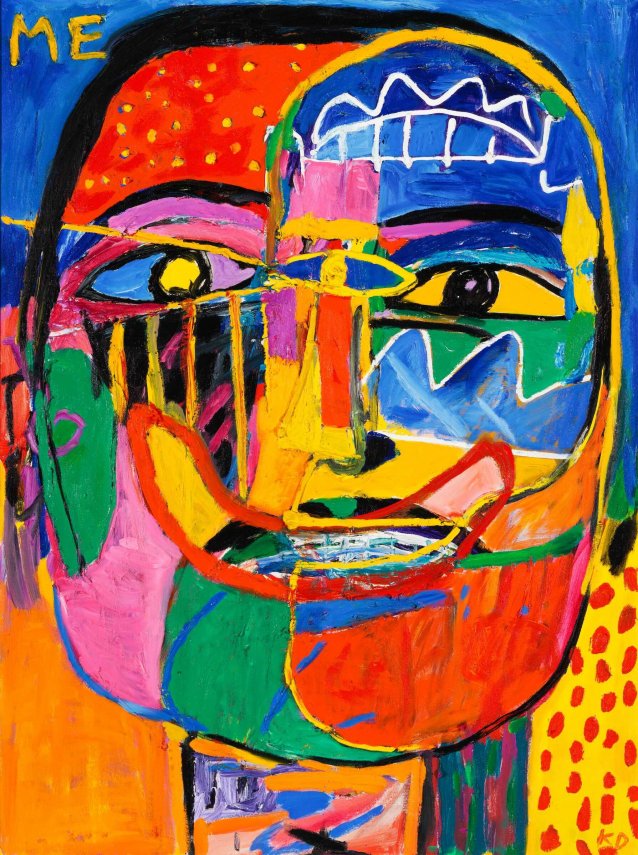

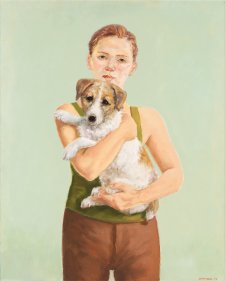

So it is that in a way, one work by the most genial and best-known of living Australian artists, Ken Done, is amongst the most blasphemous paintings in Australian art. Few if any historical paintings of the Madonna, a favourite character of Christianity and Western art alike, depict her with a dog. But in Madonna and dog, the Madonna, modelled by Ken’s wife since 1965, Judy – upon whom he’s bestowed a radiant halo – holds their dog, Spot, his curled, snoozing form proffered slightly, like an offering. Like many of Done’s works, it’s brash, cheerful and decorative; it’s also characteristic of Done’s works in that consideration of its elements, one by one, brings rewards. The body Ken’s given Judy looks to have evolved from his long study of the paintings of Henri Matisse; the colours look that way, too. As usual, Done hasn’t fussed very much over the details of Spot, but he’s captured the peaceful presence and blameless soul of the animal. In a doting, proud and protective pose, Judy tilts her head so her chin points to the yacht in the Done painting on the wall, and her left temple grazes Spot’s shoulder. A few scratches delineate her elegant brown face; her dark hair curves around her cheek to disappear down her back. It all looks so effortless and spontaneous that some might resent any scholarly considerations. Others, though, might be pleased by the suggestion that Judy’s head could have been born out of Done’s familiarity with a sculpture, made by Constantin Brâncuşi in 1910, called – non-coincidentally – Sleeping muse.

As a former advertising man, Done’s a whiz with punchlines and taglines; but its provocative title notwithstanding, Madonna and dog is only partly a joke. Done’s home on Sydney Harbour is the only church to which he belongs. As he looks at the water, the vegetation and the creatures of the harbour, he gives thanks for the life he lives. He’s a devoted parent; his family is the bedrock of his existence; his pets are family. The paintings of the great artists are his hallowed documents and relics, his hundreds of art books the texts over which he pores. It was at an exhibition of paintings by Matisse that he experienced his epiphany; a young man, then, he knew he’d seen his future. So, the painting of his wife and dog against a wall of supercharged pink and violet is a serious reflection on the profound influence of home, family and art on his imagination. It’s a deep tribute to Judy as muse and object of household worship; to the innocence of Spot; and to the glorious art of Matisse. It is funny, though.