When we say of certain people or faces that they are radiant, I suspect these days we usually mean they are radiantly beautiful. Yet this is merely one of a number of senses of radiance that ultimately descend to us from a handful of ancient mystical traditions.

The idea of a holy king wearing what the Indian art journal Marg once called a “strange smile of benign comprehension” runs parallel with the widespread currency of holy smiling among buddhas and bodhisattvas. In such smiles the observer may perceive various radiant qualities from great intelligence to “indescribable bliss.” I suppose you are less likely to interpret a “strange smile of benign comprehension” in this way, if it projects from your bank manager or the auto insurer.

Yet it was not always so. Primitive Buddhism tended to deprecate any sensations that would logically give rise to the smile, and nothing short of complete sensual evacuation was the highest pinnacle of enlightenment. Early Gandhara imagery, for example — that is, the early Buddhist art of the region stretching from Afghanistan in the west to Pakistan and northwest India in the east — is largely solemn, not unlike Classical Greek sculpture which exerted such a strong influence over it. However later traditions gradually admitted the possibility that the smile of the Buddha might not only relate to his great intelligence, shining like a beacon, but might also indicate his infinite compassion and endurance.

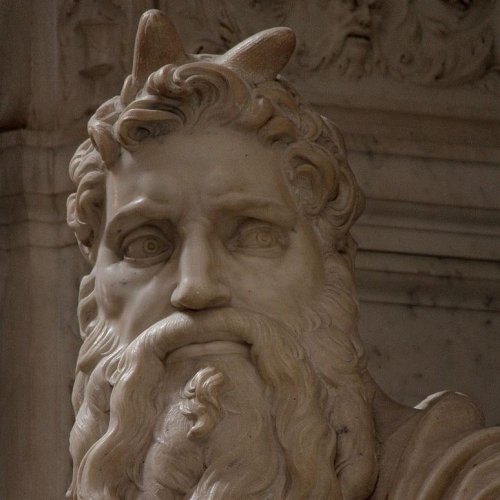

Nor is the idea that a face might radiate wisdom or “shine” confined to the Buddhist tradition. According to the Hebrew text of Exodus (34: 29-30), after Moses received the Ten Commandments at the summit of Mt. Sinai and brought down to the people the stone tablets of the law, the Prophet’s face “shone” or, literally, “sent forth beams.” The compilers of the fourth-century A.D. Vulgate Latin text of the Bible, traditionally ascribed to St Jerome, famously mistranslated from the Egyptian Greek Septuagint the Hebrew phrase “sent forth beams” as “sent forth horns.” This error eventually found literal expression in Medieval and Renaissance art, of which the most famous example is Michelangelo’s powerful, horned Moses carved for the tomb of Pope Julius II in the Church of S. Pietro in Vincoli in Rome. By the nineteenth century, when the source of confusion was well understood, the tradition of a “horned” Moses was so immovably strong that even representations of the infant Moses, lifted by Pharaoh’s daughter from among the bulrushes, still showed little clusters of beams of light protruding from his forehead in a decidedly horn-like manner.

Out of a stormy and crepuscular late January and into what one fervently hopes will be a sunnier February, we might consider whether a face can actually radiate anything at all. Is this merely cultural shorthand, set in train above all by the emotions of love and desire? Whose face or faces do you think of as radiant? Are painters, sculptors, photographers somehow complicit in reinforcing this tremendously beguiling idea?