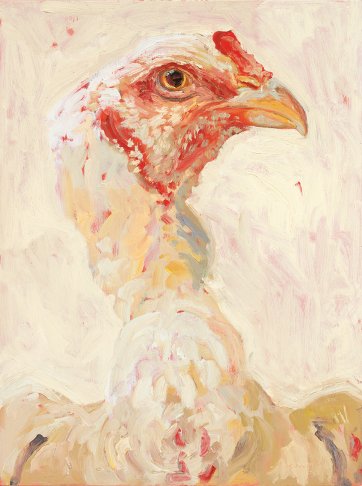

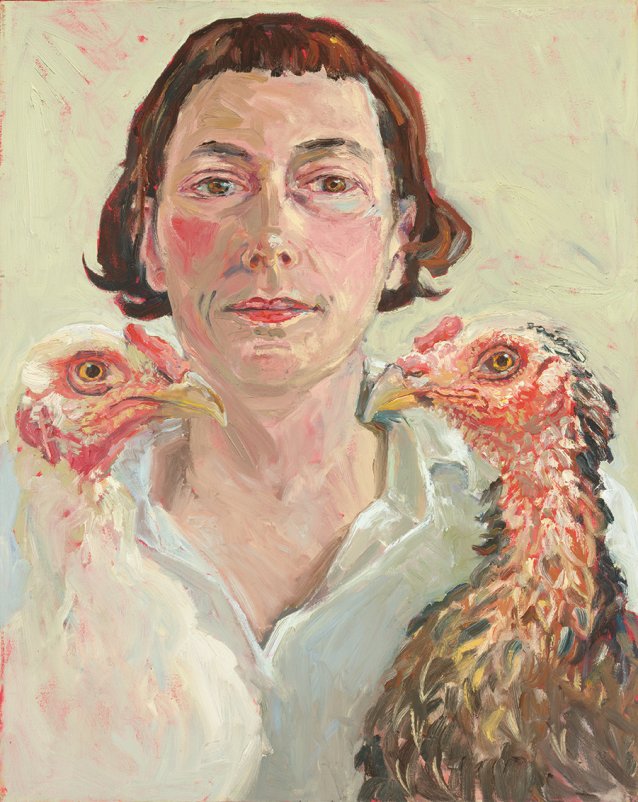

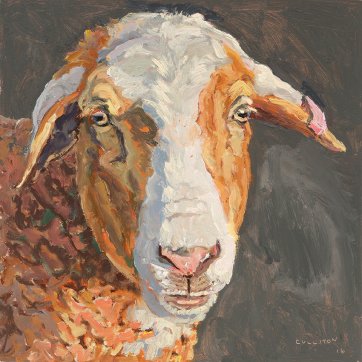

A surprising number of artists of very high reputation have painted chickens and other fowls; not just in flocks, as elements of a farmyard scene, but individually, in close-up. In turning her focus on chickens, Lucy Culliton’s not unusual; one critic’s even gone so far as to say that in looking at her pictures of the creatures, ‘one inevitably thinks of Soutine’. However, most well-regarded pictures of chickens, including the twentieth-century Russian-French artist Chaim Soutine’s, show them dead. A reliable way to tell if a chicken in a painting is dead is to check if it’s hanging upside down, because unlike, say, cockatoos, chickens don’t practise inversion for enjoyment in life.

- About us

- Support the Gallery

- Venue hire

- Publications

- Research library

- Organisation chart

- Employment

- Contact us

- Make a booking

- Onsite programs

- Online programs

- School visit information

- Learning resources

- Little Darlings

- Professional learning