Trukanini

Trukanini was born around 1812 on Bruny Island, off the east coast of Tasmania. She was the daughter of tribal leader, Mangerner, and grew up on her traditional lands in the D’Entrecasteaux Channel area.

In the 1820s, the traditional culture of Trukanini’s family was severely disrupted by violent clashes with sealers and white settlers. By the age of seventeen, she had witnessed the brutal abduction and murder of her mother, stepmother, uncle, sisters and future husband, Paraweena.

On the mainland of Tasmania, relations between Aboriginal groups and European settlers were also fast deteriorating. Part of Governor Arthur Phillip’s solution was to appoint ex-builder, George Robinson, as ‘conciliator’ in 1828.

Robinson’s first task was to gain the trust and friendship of Aboriginal people as a way of protecting the safety of the settlers and controlling the movements of Aboriginal people. He moved to Bruny Island, where he attempted to establish an Aboriginal mission, but his settlement proved a failure, with large numbers of people dying from European diseases in the first year.

Trukanini first met George Robinson at the Bruny Island mission. At eighteen, she immediately impressed Robinson with her intelligence and strong command of the English language. For Trukanini, Robinson was the first white man she had met who treated her with any kindness.

There are many different spellings of Trukanini's name including Truganini, Truganina, Trugernanna, Trugernanner, Trucanini, Trucaninni, and Trucaninny. This resource adopts the spelling used by Tasmania’s Palawa people, Trukanini.

With a new plan to go bush in order to make contact with other Aboriginal people, Robinson persuaded Trukanini to accompany him as a mediator and translator. Trukanini was convinced this was the only way to protect her people, later recalling,

It was the best thing to do. I hoped we would save all of my people who were left. Mr Robinson was a good man and could speak our language and I said I would go with him and help him.

Setting off on a journey across Tasmania, Robinson’s real aim was to encourage Aboriginal groups to relocate to a ‘friendly mission’ on Flinders Island. People were guaranteed tea, flour, sugar, clothing and protection from being shot, along with a promise that they would be returned to their homes as soon as the danger was clear.

Robinson established the settlement Wybalenna on Flinders Island. The Aboriginal people who resettled here were not permitted to speak in language or perform traditional ceremonies.

But Robinson’s plan unravelled immediately. En route to Flinders Island, two thirds of the 300 people who had agreed to resettle died in jails and transit camps. The tragedy continued when they arrived on the Island, with another 29 people dying in the first twelve months.

Robinson was saddened by the deaths, but defended his actions saying,

The sad mortality that has happened among them is a cause for regret, but after all, it is the will of providence and better they died here where they were kindly treated.

While the ‘friendly mission’ had failed the Aboriginal people dismally, the officials in the new state of Victoria clearly thought otherwise and offered Robinson the lucrative position of Chief Protector of Aborigines. Robinson accepted the role with a request that the 75 remaining inhabitants of Flinders Island be relocated to Victoria.

The new Victorian government eventually agreed to Robinson bringing 15 people, including Trukanini. However, Trukanini, having no knowledge of the language or country, was eventually set free when Robinson realised she had no influence in his negotiations with local Aboriginal groups.

In 1841, Trukanini and four others, were arrested and charged with the murder of two sealers. Robinson visited Trukanini in jail and testified on her behalf, saying ‘I am indebted to that woman for the preservation of my life on one occasion at Arthur’s River. She swam and took me across.’

Trukanini was found innocent, but her two male companions were not so lucky. Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner were hanged in the first public executions in Victoria’s history.

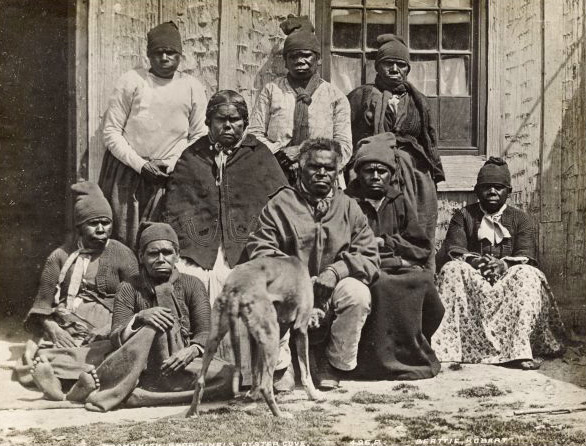

Trukanini returned to Flinders Island where she found only 46 survivors at the settlement. When the community petitioned the governor to remove the cruel new manager, the response was to relocate them to an old jail at Oyster Cove, south of Hobart. In photographs taken of the settlement, many including Trukanini, it is not hard to see the broken spirits of people betrayed by Robinson and his promise of returning them home.

By 1869, Trukanini was wrongly considered the ‘last of the Tasmanian Aborigines’. Aware of the growing international trade in Aboriginal human remains, Trukanini had every reason to fear what could happen to her after her death and pleaded with a friend, ‘Promise. Don’t let them cut me. But bury me behind the mountains.’

The trade in Aboriginal human remains was largely based on Charles Darwin’s new science of evolution that suggested Tasmanian Aborigines could be the most ‘primitive people’ on earth.

Trukanini spent her last years in Hobart, where she was given the bogus title of ‘Queen of the Aborigines’. Although she was publicly mourned when she died in 1876, her worst fears were made real when her remains were displayed in the Tasmanian Museum. It took another one hundred years to correct this injustice and, in 1976, Trukanini’s ashes were finally scattered with due ceremony on the waters of the D’Entrecasteaux Channel.