Australians in Hollywood celebrates the achievements of Australian artists in the high turn over, high competition American film industry. From our pioneers of the silent era (Louise Lovely and Annette Kellerman) to the Oscar-winning stars of the so-called “Australian invasion” today, this exhibition showcases over 80 Australian actors and technicians who’ve cut it in Hollywood.

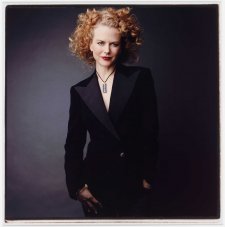

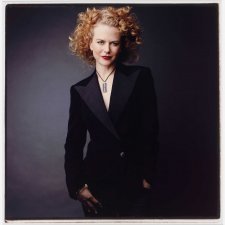

When Nicole Kidman accepted her Oscar earlier this year, she joined Russell Crowe, Geoffrey Rush and Mel Gibson among fellow Australian Oscar winners. She also became the latest in a long line that stretches back to cameraman Damien Parer collecting Australia’s first Oscar in 1942 for his wartime documentary Kokoda Front Line. In the years since, Australians have won Academy Awards for acting, direction, costume design, music, animation, special effects and other important technical achievements.

Australians in Hollywood features the current crop of stars including Russell Crowe, Nicole Kidman, Heath Ledger, Cate Blanchett, Hugh Jackman, Eric Bana, Rachel Griffiths and Geoffrey Rush, as well as those behind-the-camera: Bruce Beresford, Gillian Armstrong, George Miller and Peter Weir, telling the often fascinating stories behind their success on the international stage.

The exhibition also reaches back into cinema’s classic past looking at the swashbuckling Tasmanian, the Australian James Bond, the notorious swimmer and the glamorous faux Australian.

Australians in Hollywood is curated by the National Portrait Gallery and is proudly sponsored by ActewAGL.

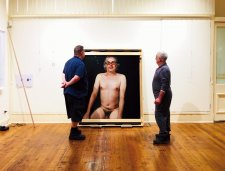

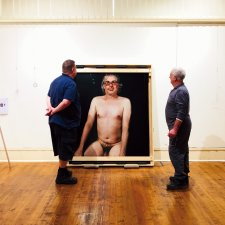

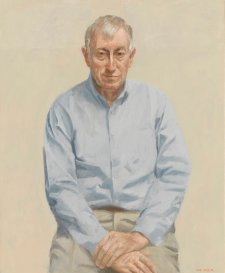

Geoffrey Rush opens Australians in Hollywood , Commonwealth Place, 13 November 2003

I've written something special for the occasion…with apologies to Tim Winton and Cloudstreet:

Will you look at us on Sunset Boulevard! The whole restless mob of us in designer clobber in the dreamy Californian sunshine skylarking and chiacking about for one day, one clear, clean sweet day in a good world in the midst of our living. There's Nicole and Cate and Russ and Heath; Toni and Naomi and Rachel and Guy; and Baz and Mel and Sam and Eric….and Hugh and I!

The franchised billboards loom announcing their names, LA is a twitching backdrop, it's a Melrose red-carpet world-class sausage sizzle. A punch-up flares. A real Koala blue.

They're a breath of fresh air, there's a different twist to their talent.

Is it fearlessness? A hard-wired Hibernian love of a good yarn? Something in the vegemite?

They're rugged and unpredictable, sexy and dangerous and sweet.

There are Logies spilling from their knapsacks and Fendi bags, mutating into golden men of the Academy. Arm in arm they drop their notoriously chameleon international vowel movements and yak in the charming strains of their native tongue.

G'day, youse yanks, they all say, sprawling and drinking.

The speech is silenced by a melodious belch which gets big applause.

One of them breastfeeds a baby, another blurts on its belly and a song strikes up. It segues into old forgotten Antipodean TV themes and climaxes with a hearty chorus of Louie the Fly. Unless you knew, you'd think they were a whole group, an earthly vision.

I'm trying to find Hollywood . Is this it? For those who barrack and preen and report and have never grown out of the school house colours and loyalties of sports day, maybe so.

Or is it a twilit Sunset Boulevard of Broken Dreams? The blacklisted Hollywood 10 that split the creative community during the baiting of communists? Is it Kenneth Anger's Babylon ….perhaps Singin' In The Rain

or The Day of the Locust . Godzilla stomping all over New York or a frizzed blonde chorus girl backstage in black and white answering a phone, chewing gum and saying ‘go ahead, it's your dime'?

Well, I am an Australian and apparently I've been to Hollywood . But I don't know where or what it is. Geographically I do. Strangely enough I did shoot a scene with Goldie Hawn for The Banger Sisters at the rear of the Hotel Roosevelt which is the heart of Old Hollywood. We were pretending it was a hotel in Phoenix , Arizona . “We are actually filming in Hollywood ” I whooped….innocently. She said, “ I know, honey, I've never done that before either...tee-hee!”

I hardly ever see any Australians there. We don't all get together at the Outback Pub. I waved to Cate once on a red carpet, I saw Judy a couple of times at the airport. I did have one quintessential Oz experience. I was a guest at the Australian-Los Angeles Chamber Of Commerce Australia Day Dinner packed with expats who I could tell hadn't actually lived in Australia since well before Hawke was elected. One old codger sidled up to me and confided with a twinkle “I've seen all your movies, Geoff. GOOD EFFORT!” I felt like I was home, but in primary school.

That elusive cinematic arcadia referred to for its legends and glamour, and just as easily disparaged for its tackiness and scandal, it's all individually floating about inside our heads. A daydream.

In reality it's a business-driven conglomerate of about seven corporations who produce and distribute the majority of international product.

I suppose in the bottom of my heart I'd love it to be the perception not the reality. I do love the myths, the iconic dreams, the artificiality of it all.

In my head, and perhaps in yours, I am chauffeur-driven in a tinted windows stretch limo as the classical archway of Paramount Studios glides over my head – when in fact I'm driven in a town car through the Disney boom gate while they search the car for bombs, check my photo ID around my neck and say thanks, “Go on through Mr Bush”. True story.

My first proper day in Hollywood was in Prague . Before Shine had even been released in America , Bille August, the Danish auteur, had cast me

despite all of my doubts and protestations, as a cop, a nineteenth century cop in Les Miserables . He primed me to bamboozle the system as well as myself. I thought if I'm going to do something international, there's not a lot to lose so why not dive from the highest tower into that square inch blue pool below and drop screaming, and not care if my swimming shorts ballooned as I pedaled through the air. Daring should be part of the game. As is being scared. Most actors I know work from a highly disciplined sense of terror. Certainly on the first few days.

I'm standing in a beautifully realized fake French village, wearing an impossibly stupid large black hat, repeating my mantra “you've just won an Oscar, you've just won an Oscar.” I felt like my great-great-grandfather. Earlier that same year I'd shot a film in Glen Innes which is where he settled in the 1850's. Nineteen miles outside of that Celtic haunt. Via a local historian I found his wife's unmarked bush grave. After six months on a boat, having left Ireland forever, he must have felt like he was starting life again on Mars. As did I. But I took a deep breath, said my lines, learnt a lot from the Italian designers, the Scandinavian camera department, the Czech crew and the Irish, English and American actors. The film bombed. But I know that I grew.

Most of my American films I've shot elsewhere. All over England. Or Mexico. Or with Ned Kelly an hour out of Melbourne.

Somehow I seem to have played a lot of historical figures – wayward heroes like the Marquis de Sade and Trotsky and Peter Sellers. It feels like an expansion of my life here in the theatre. I like good dialogue, strong scenes, stories with some meat on the bone. Or at least with a bone. I work consciously on a diverse repertoire. But you still get that occasional Australian journalist who can only ask “So how big's your trailer?”

I said, “Are you phoning from your office? She said “yes”. I asked how big is that. She told me. I said my trailer is smaller. The point I'm making I continued is that there's this facile size of ego size of trailer size of part penis-envy mythology that's got to stop!! It's not about that. This is my green room, MY office, dressing shed, holding stall, kids creche…whatever you wanna call it. It's practical.

But then when I shot Mystery Men at Universal, on an adjacent lot I saw Kevin Costner's Winnebago. It was the size of a boutique hotel. It had several stories. There were interior staircases. Even the pushouts had pushouts!

I over-react to what I perceive is trivia but really I know it's puff gossipy journalism. But I'm compelled to remind people that what we do is a job, a creative one, a craft. The word actor has been hijacked. Because of the blow-out in puff journalism, we're now all roped in with footy commentators, models, lifestyle hosts…the metaphoric catwalk. I hate using the C word in public…but we've been turned into a pack of …celebrities.

The obsessive focus on that aspect I believe creates a kind of cultural amnesia. There's 90 per cent of the iceberg that goes unexamined – only the faddish ‘Now'. Nothing from the past. Very little about the grass roots teams that constitute the bulk of the industry here.

I love the history here tonight. The thrilling scope of it all. I love the thought that some of our very early pioneers probably went to the set on a dray. A stretch dray…there's a thought. Under the pressure of 10 decades, it reflects as is inevitable in the history of a creative industry, enormous upheavals, cycles of fashion, financial and artistic spurts, national pride.

This cavalcade of snaps is not a finite collection. In the decades to come there'll be more – the current fashionables will yellow into age, reach a use-by date and drift off into memory, perhaps obscurity.

The outward story IS one of triumph and a unique and fertile contribution to global cinema.

The hidden story is more poignant and tougher. It tells you that as a practitioner and as a country you rise and you fall, you come and you go, that there is a strange haphazardness to it all. Do you know the biggest year ever in Australian production – our greatest output was 1911. There followed exhibition and distribution wars, as happened again in the thirties, and indeed still do.

We can enjoy the extraordinary diversity of what we know are undoubtedly capable of, but it always to me is tempered by a fragility – a sense of impermanence.

I remember seeing Peter Finch in The Shiralee when I was seven. But at that time I never really saw my life or the life around me on a cinema screen. We had lost the vitality of our prodigious and highly original silent film and early talkies industry for four decades. It could easily happen again.

Hollywood dominated our screens and claimed Peter Finch, Leo McKern, Judith Anderson, Errol Flynn, Cecil Kellaway. They went over there because it had dried up here.

I'm always asked particularly in North America “so what's with this Aussie invasion, why is this boom happening?” It's a long answer. I normally try and sound bite it up by saying we have a secret laboratory in the Outback where we clone the actors to leash them zombie-like on an unsuspecting sleepy Hollywood village.

But the real answer? We witness tonight, let's call them the cherries. I always prefer to talk about the cake.

My professional career started in 1971 because an Act of Parliament founded the Queensland Theatre Company. Whatever success I'm perceived to have in Tinseltown springs from that reality. I have always been the fortuitous product of Government subsidy. Completely. It trained me for twenty five year for my overnight success in Shine .

NIDA was founded in 1959, the VCA in the mid-seventies. Active legislation from the Gorton government ensured the backbone of our industry in the creation of the first Film and Television school which flourished through the cultural upheaval of the Whitlam years. A whole generation has experienced an unquestioned presence of Australian life expressed in film. I witnessed a hard-won, magnificent re-birth.

Thirty years after my debut I was back in Brisbane shooting Swimming Upstream and I was awe-inspired by the confident unquestioning attitude of people in their early 20s working with highly sophisticated skills and experience around the camera, in design, art department, props. Unheard of, unthinkable when I was their age.

Younger actors now maybe don't get to spend three years in a theatre company, but a young thesp might spend a season or two with a throughline role in The Secret Life Of Us or Stingers seeking self-definition as an actor, testing their waters. This only happens because a government controlled quota system creates that opportunity.

If we lose any of that legislative framework and control, we leach the soil that nourishes and eventually produces this celebrated flowering.

To hang the next lot of portraits here, we must understand these things intelligently and astutely, treasure and protect them for a feasible and desired future. So as artists we are able to retain our special brand of us, and quite simply be able to ply our trade.

I'm proud to be a sentence in this big story. I like climbing the branches of the family tree. It inspires me and defines me, mysteriously, as an actor to possibly be a twig on the sturdy limbs of say a Frank Thring, a Robert Helpmann or a latter day Coral Brown. Errol Flynn's Fletcher Christian is waving I think to Russell's Master and Commander .

You know, we could easily fall prey to exporting a national character and its simple stereotypes but what surrounds us in there is so much broader than that – it's huge and vast and wonderful.

I'm thrilled to be able to launch it. We're all in some way reflected in these portraits.