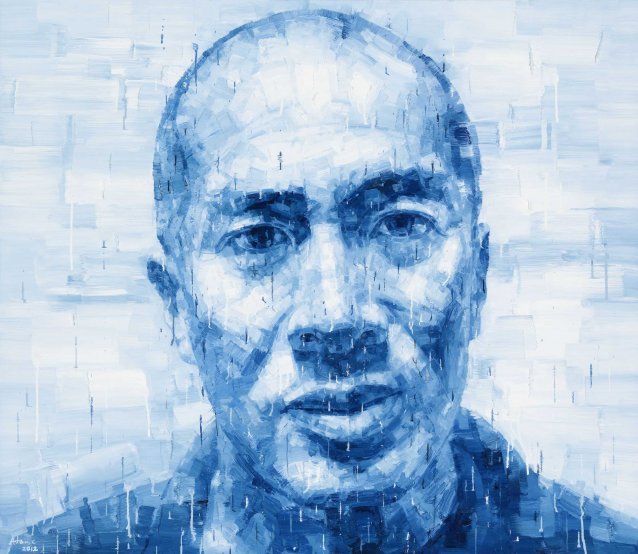

Professor Charles ‘Charlie’ Teo is passionate about brains and the people they belong to. It might seem an obvious statement to apply to Australia’s most well-known neurosurgeon – and one who’s transcended pure clinician status to become a celebrity of sorts – yet so many people, high-profile or otherwise, pursue careers as a function of beige-infused motives such as remuneration, status or blunt familial pressure. The earnest, endearing zeal that Teo projects as he speaks banishes any such possibility in his case. I’m here at his rooms at Prince of Wales Hospital in Randwick with colleagues from the National Portrait Gallery to film a Portrait Stories interview. The Gallery acquired an arresting painting of the neurosurgeon by multiple Archibald finalist Adam Chang in 2013, and, as the conversation flows, it becomes an intriguing experience reconciling the pensive, almost vulnerable countenance of the sitter in Chang’s layered-blue work with the live version before us.

We start by asking about Teo’s early days, where we discover we might have lost the neurosurgeon to the lure of another field requiring ample skill and dexterity: ‘My mum tells me that when I was a child I use to look out the window when the garbage men would come by. They're very athletic, wearing singlets with big muscles, jumping up on the back of the truck and looking incredibly active and fit. I used to aspire to become a garbage man when I was a young fellow!’ The simple pleasures of physical exertion were to lead to a black belt in karate later on, and Teo pursues a dedicated regime to this day, incorporating kayaking and swimming. He explains that the fitness is crucial to ensure he is at his best for surgery; to emphasise the point, the lean fifty-eight year-old is clear and concise despite speaking to us after only a few hours sleep, having performed a six-hour operation the previous night. ‘It's six hours of staring down the microscope, perfectly still, arms up like this the whole time and not resting, and concentrating on someone’s life in your hands.’ It strikes me as a gruelling stint, but in fact his longest ever operation was over four times as long, clocking in at a brutal twenty-six hours.

Teo credits the influence of his mother – a ‘tiger mum’ and ‘his biggest inspiration’ – as providing the first push towards medicine, but it was his initial love of the field in challenging circumstances that drew him onwards and upwards into the lauded career to follow. He notes ‘the first time I was exposed [to neurosurgery], I was doing paediatric neurosurgery ... As a registrar, you are basically the man on the ground at the call phase. You see all the emergencies; you see the kids that come in with bad head injuries that you've got to try and salvage in the emergency room, and often you’re operating on your own. Yeah, I was thrust in the deep end, but I loved it.’

The evolution of Teo’s career now sees him operating and teaching pro bono in developing countries for several months a year, as well as promoting the Cure Brain Cancer Foundation, which he founded. His caseload is made up predominantly of patients afflicted with brain tumours that are deemed (by other surgeons) ‘inoperable’. For many people, Teo is the ‘last chance saloon’, a desperate detour from grim euphemisms such as ‘putting your affairs in order’. It’s his willingness to operate in these cases that has drawn enormous acrimony from many of his peers, with labels such as ‘maverick’, ‘cowboy’ and ‘narcissist’ bounced around, as well as accusations of ‘offering false hope’. The patient stance is rather different; there is a long list of testimonials from sufferers and families lavishing praise upon him in instances where Teo has extended and indeed saved lives. The duality of perspective is genuinely stark.

Teo’s simple answer to the ‘maverick’ charge is that it’s not something he ever aspired to be, and that neurosurgery is hard enough without having the knives of your peers pointed firmly at your back, waiting for you to fail. He points out ‘I don’t need that pressure … I would love to be considered by my colleagues as just another neurosurgeon’. Fortunately he has a fantastic support network, starting with his wife and four daughters, to mitigate the stressful elements. ‘When I go home, I have this incredibly fulfilling family life; I have fulfilling pastimes.’ He notes it’s his family and friends that give him ‘the broad shoulders to put up with all the pressure’.

While Teo is resigned to the ill will from colleagues, he doesn’t resile from the importance of pushing boundaries, and challenging dogma and the status quo in medicine. He refers passionately to Australian pioneers such as Nobel laureate Barry Marshall, who consumed the bacteria Helicobacter pylori to confirm its role in stomach ulcers, and gastroenterologist Tom Borody, whose faecal transplant therapy (yes, it’s what you think it means!) has seen remarkable results in chronic conditions such as Crohn’s disease. They too copped criticism from their medical peers.

So what is behind the medical establishment’s antipathy towards Teo? How do we reconcile it with broader acknowledgements, such as his Member of the Order of Australia honours in 2011? Teo points to medicine’s entrenched conservatism and the challenge he represents to its established norms. The concepts of ‘inoperable’ and ‘false hope’ are instructive here. Teo explains that surgeons are trained to evaluate ‘quality of life parameters’ and that ‘inoperable’ is usually a mischaracterisation – in fact, it means a surgeon has determined that risk/reward considerations mean it is not worth operating. Thus, offering to operate is offering ‘false hope’.

The omission in this equation is, of course, the patient’s perspective. So – the surgeon is projecting his own concept of ‘risk-reward’ for a given scenario (IE – ‘I wouldn’t take that risk if it was me’) – but not considering where the patient stands (IE – but it’s not you!). This is where Teo veers off-piste, adopting an approach based on patient autonomy. In his model, Teo takes the time to present all the details and risks of surgery as clearly and dispassionately as possible. This might include presenting a percentage figure for the likelihood of paralysis or speech loss, or how much more time might be bought in the event of successful surgery on an incurable malignant tumour. With the detail provided – and the time taken to discuss the person’s life and support networks – the patient can then determine if they want Teo to operate. He explains, ‘I say to my patient, “You’ve got to determine what is quality of life for you.”’ Of course, not all operations go to plan; along with the fairytale results in his career, Teo readily accepts he has made mistakes, and people have suffered and died as a result of them. He notes, ‘It’s the unsuccessful cases that really teach you the greatest lessons’.

Teo describes a case presented in his 2015 TED talk which was a revelatory moment is his career. A patient, Fiona, presented with a benign brainstem glioma (brainstem growths are the most dangerous and difficult to operate on; the orthodox view is they are almost always inoperable). She had accepted advice from a neurosurgeon seven years earlier that the growth was inoperable. The tumour had since rendered Fiona a quadriplegic and was now becoming life-threatening; she was told she had weeks or months to live. Teo advised he was willing to remove the tumour, but it wouldn’t change her quadriplegia, so did she really think it worthwhile? Fiona took Teo to task, telling him that quality of life for her was being alive to offer continuing advice and guidance to her teenage daughters. He was shocked, realising he had been projecting his own values of ‘quality of life’ (where physical aptitude, for example, was so important) rather than considering the patient’s ... and perhaps it was something he had been unconsciously doing for years. It was a defining experience for him and strengthened the convictions underpinning his practice model. The operation was a success, and, at the TED talk, Teo showed a picture of Fiona, still doing well ten years after the operation.

Charlie Teo’s mix of self-belief, skill and patient advocacy are an asterisk of hope for people whose lives are looking like being indiscriminately cut short by brain tumours. He is a problem for medical orthodoxy because he represents a devolution of authority: instead of clinicians being the sole arbiters of patient destiny, he seeks informed patient input to qualify/ instruct that decision-making process. He has argued that, if at all possible, clinicians should ‘respect and nurture hope, not shatter it’. Of course – we should absolutely respect the need for medicine to be guided by principles of scientific rigour and evidence, but it’s difficult to accept this concept must be mutually exclusive with a practice model that is, essentially, a ‘second opinion’ – something we hope a robust medicine would always embrace.