According to 2015 figures released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics earlier this year, over 28% of Australia’s population was born overseas. In excess of a quarter of the national population, then, has gone through, or is going through, the experience of adjusting to a new culture. For some, this might be a relatively easy transition from an English-speaking, Anglo-Celtic culture to one strongly influenced by an Anglo-Celtic colonial history. For others, it might entail exposure to a different language, religion and system of governance, as well as smaller changes such as alterations in diet or variations in social customs.

Queensland artist Jacques van der Merwe left South Africa in 2008 with his wife, Madeleen, and two children, to find a place where he could raise his family without the constant fear of crime and potential for violence he experienced in Pretoria. While happy to find a peaceful haven in Australia, Jacques and Madeleen left family and friends and moved to a place where they knew nobody. At the time, Jacques was just beginning to establish a reputation as an artist in South Africa, and by moving to Australia he had to start all over again. For the first few years, the family was unsure if they would be allowed to remain in the country, as they tackled the bureaucratic quagmire of applying for permanent residency. Jacques found himself surprised by how hard it was to adjust to this new land; this was the genesis of the New Arrivals project, which he started after finding himself comparing stories with other new migrants.

Upon moving to Mount Tamborine, in the Queensland Gold Coast hinterland, Jacques found a community of artists and writers, many of whom were also born outside Australia. He began the New Arrivals series in 2012 with portraits of some of these new friends, accompanying each painting with a taped interview with the sitter, describing their story. Some had been in Australia for decades, like the ‘ten pound pom’ neighbour, Terence Kitching, who came here as a young man in the early sixties, seeking adventure and taking advantage of the White Australia Policy. Others, such as German-born artist Brigitte Doering and American artist Mike Taylor, came here as tourists and fell in love with Australia and an Australian partner, enabling them to stay. Like Jacques and his family, all speak of their feeling of gratitude for being able to live in this country, but, with a reticence that almost borders on guilt, they speak of the difficulties they experienced adjusting to a new environment.

The next group of New Arrivals that Jacques sought out to paint and interview were refugees, finding themselves here in Australia after fleeing their country of birth. Iranian-born Vahid Eshraghi was a student studying in the Philippines in 1979, when the Iranian Revolution saw the overthrow of the US-backed Pahlavi dynasty, and the establishment of the Islamic Republic under Ayatollah Khomeini. At the time, his mother in Tehran told him not to return to Iran, and he found himself homeless, and, when his passport expired, stateless. Eventually he met an Australian Immigration Attaché in Western Samoa who encouraged and helped him apply to come to Australia as a refugee. Hamed Zwafa, a more recent refugee from Iran, tells an even more dramatic story, fleeing prison, torture and likely execution in Tehran as a student activist; he is currently seeking a permanent visa in Australia.

Two more recent refugees, Senait Asmelash and Bebe Selenani, were both painted and interviewed the year they arrived in Australia in 2012. Senait Asmelash was born a Christian in Eritrea, and, fearing a lack of religious and political freedom, she fled to a refugee camp in Sudan, a country where Islamic Sharia Law applies. Bebe Selenani was escaping the continuing civil war in her country of birth, the Democratic Republic of Congo. She fled to Tanzania with her four small children and, from there, applied to come to Australia as a refugee. The two tell us stories of past hardship and devastating loss, and yet their experience of this new country is expressed primarily with relief and gratitude.

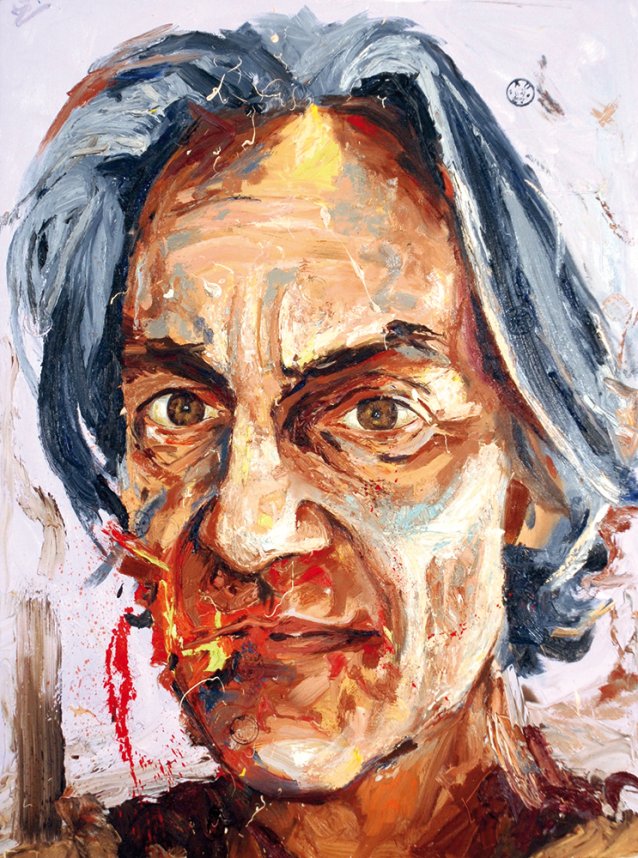

The initial group of portraits, painted in 2012, was first exhibited at The Centre Beaudesert in 2013. For a second exhibition at Logan Art Gallery in 2015, Jacques added new portraits of both migrants and refugees living or working in Logan. As a migrant myself, Jacques asked if I would agree to be interviewed and photographed for one of these new portraits, and, with some trepidation, I consented. Born in Ireland, I came to Australia forty years ago, working on a horse transport plane, not really knowing what I wanted to do or where I wanted to be. I was escaping family pressure to join the army in England, and I had a vague idea that I wanted to work in an art gallery. Like Jacques’ first sitters coming from Britain, Germany and America, my personal difficulties adjusting to the new culture of Australia were insignificant compared to those of the refugees.

Just as some found it easier than others to adjust to life in a new country, some also found it easier than others to share their stories with the world. One young woman, who migrated from South Africa in 2009 at the age of seventeen, initially agreed to be interviewed and painted by Jacques in 2013. However, when hearing her own words posted on the artist’s website, she found it too confronting, the experience dredging up too many unpleasant memories; she asked the artist to remove it. The painting still appears on the website as it was exhibited at Logan, covered in a semi-transparent gauze so that the subject appears to be emerging from the mist, or perhaps fading away. Other sitters, such as the young refugee from Rwanda who Jacques interviewed and painted in 2012, have allowed their portrait and interview to remain, but requested that they be listed as anonymous.

The New Arrivals portraits are all 122 x 91 cm; they are the same dimensions so that all are equal, like enlarged passport photographs. Each work is intended to be viewed with the accompanying interview, accessible via a QR code on the label when exhibited, or directly through the artist’s website. They are painted quickly with bold expressionist brush strokes, the composition loosely dictated by snapshot photographs taken while interviewing the sitter. By painting fast, Jacques allowed details derived from the sitters’ stories to appear almost without his conscious control. When painting Bebe Selenani, four babies, representing her four children, appear to float around her neck, emerging as both a beautiful garland and a restricting yoke. In the portrait of the anonymous refugee from Rwanda, one of her white bead earrings has transformed into a skull. In my portrait, a disconcerting bloodlike splash appears by my mouth.

New Arrivals is a visual and oral portrait of ordinary people representing over a quarter of the Australian population. We have all come from different parts of the world, carrying some degree of loss from what we have left behind, and each one of us has sought a better life in this country. In seeking to come to terms with his own immigrant experience, Jacques van der Merwe has given voice to a seldom heard minority and reminded us all to treasure our relative freedom and prosperity.