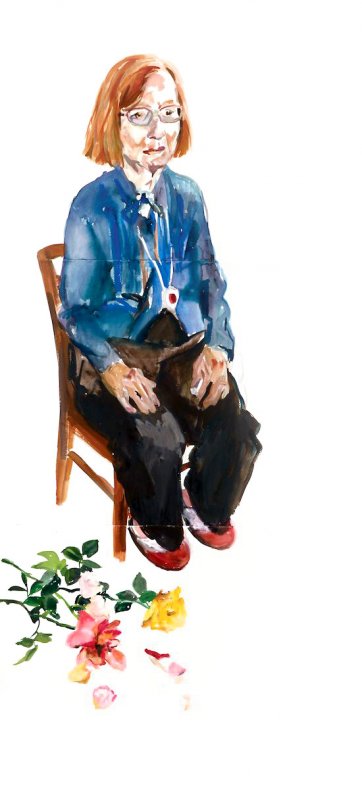

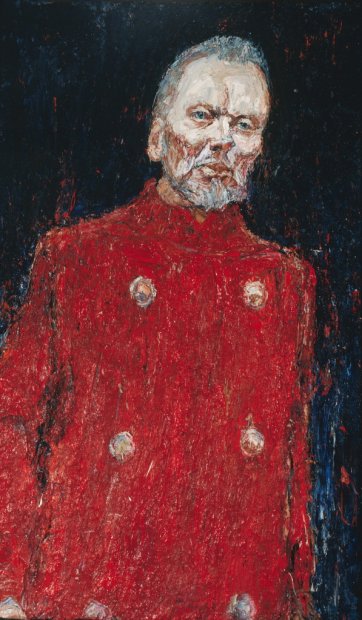

The portrait of Weiss borrows from the palette of Harding’s glorious oil paintings of peonies. There’s something about it that evokes a historical portrait of a European nobleman; the red wrap is the colour of the cape of Raphael’s Pope Julius ii from 1511, and the colour and folds of the cloth recall the ‘turban’ in Van Eyck’s Portrait of a Man from 1433. Compositionally, it’s strong, with a sturdy cross brace formed by the rosy scarf hanging straight, and the crimson tossed horizontally. With his sceptical expression mixed with both a tinge of hope and the threat of starting up with a roar, the painted Weiss has the visage of an old king, tired of contenders and conspirators. Indeed, perhaps we can put his air of vulnerability down to Harding’s attentiveness to minimal gestures and momentary glances that round out a character – Lear, for example – on stage.

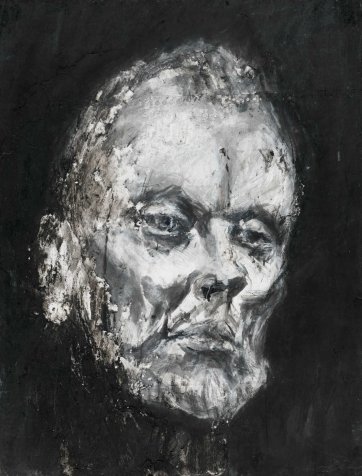

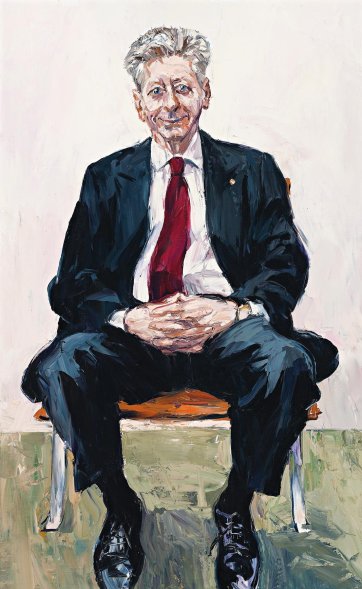

Harding’s mostly painted portraits for his own edification, and his subjects have been his friends and their friends, people from the Sydney art, theatre and music scenes. The picture of William Cowan, however, was commissioned by Trinity College at the University of Melbourne, on the board of which Cowan served from 1987 to 2013.

Oddly enough, this painting of an engineer who became a career company director and now advises senior executives is one of Harding’s most arresting and convincing portraits.

By Harding’s standards, the portrait of Cowan isn’t a colourful picture, but the artist enjoyed the challenge of painting only the second suit of his entire career. The neutral backdrop is tinted with the red of Cowan’s tie; similarly, there’s a suspicion of red in Cowan’s white shirt. This helps a great deal in pulling the work together. As an artist who paints a lot of bare feet, feet in sensible sandals and Sydney-style loafers, Harding’s particularly pleased with the job he did on Cowan’s shiny business shoes. Although shoes in a pair are the same, they can’t be painted the same, because of the way the light hits them: the highlights on the shoe on our left are light grey, those on the shoe on the right, violet. In contrast to Weiss’ feet, which moved off the canvas because of the way the figure evolved, Cowan’s feet were never intended to appear entire. The missing toe sections draw the eye out to the space beyond in a tactic contributing to the portrait’s dynamism. Cowan looks benign and zesty; we feel he’s about to jump up and pursue a positive initiative.

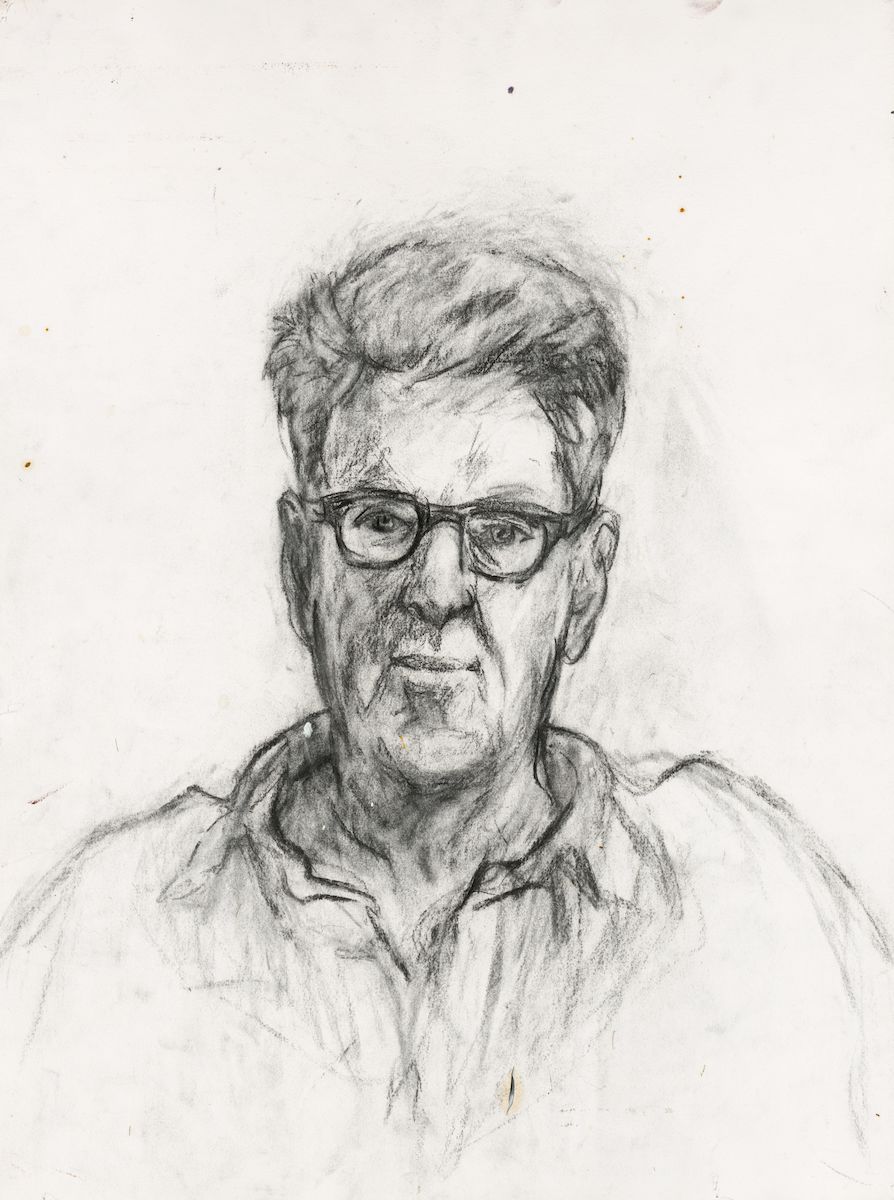

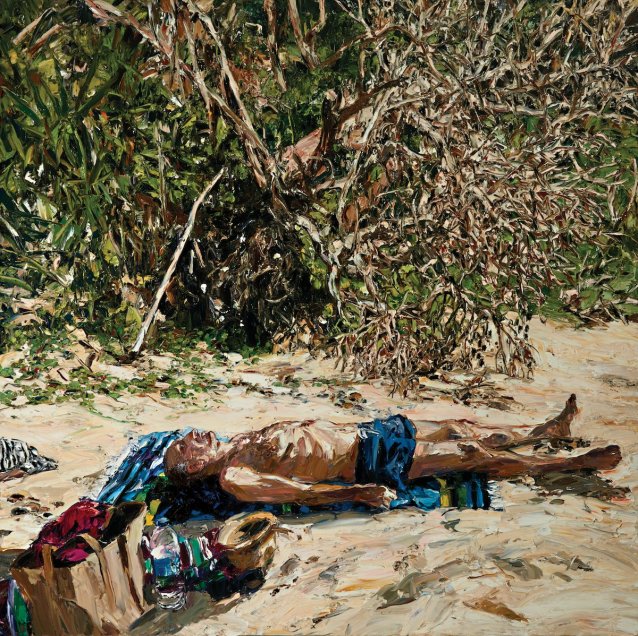

Robert Drewe doesn’t look so effective in Harding’s great portrait from 2006, and it’s not just because he’s bared to the elements. His expression is wounded and wary.

Robert Drewe, author of The Bodysurfers, The Rip, The Drowner and The Shark Net, was just the man to open a group exhibition called The Sea for Harding’s long-term art dealer, Rex Irwin, in 2005. Soon after, Harding contacted him about the possibility of a portrait. That summer, Harding began a series of drawings of Drewe on the beach around Byron Bay. The author found it discomfiting to be studied at his leisure. The painter was alternately pleased and depressed by his own efforts. Several attempts were scrubbed out. The holiday season ended. After a break, the sessions resumed. During this time, Harding looked up from his work to see that Drewe had lost focus, for a second, on the portrait process. Just as he did for the portrait of Bell, and, years later, for that of Weiss, Harding seized on a ‘look’ of which his sitter was unaware – one that ran counter to his jovial public demeanour.

Only having conceived of Drewe’s face did Harding decide on his figure. That came to him as he was bobbing in the sea, lazily attending to the different tempos of wavelets and ripples against his chest, squinting at the blending blues of water and sky. He went back to Sydney and painted Drewe’s body convincingly submerged, achieving that difficult effect by painting the water itself in smooth, curving strokes of green, white and pinkish light brown. It’s a cheering fact that the actual Robert Drewe’s much happier now than he was, unbeknownst to Harding, 11 years ago; but the man in Harding’s perceptive and intelligent portrait won’t ever have any confidence in his capacity to recover from the situation he was in when he was painted. We meet his eyes, and a wave of humaneness drags at us.

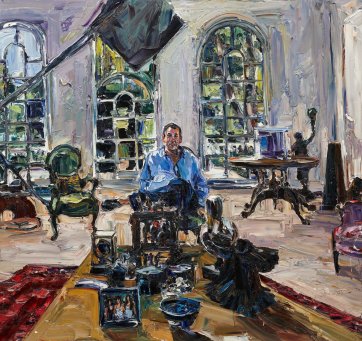

The differences between the portraits of Robert Drewe and John Feitelson exemplify the contrasts that occur throughout Harding’s work. One man’s represented outside in the glare, the other inside in shadowy, wobbly light. Drewe’s unclothed and Feitelson wears jeans and boat shoes. Drewe has nothing and Feitelson’s surrounded by his chattels. Drewe’s head occupies fully one quarter of the canvas, and looking into the extraordinary painted mess of his eyes we come close to swallowing the notion that a painted portrait can reveal something of its subject’s psyche or ‘soul’. Feitelson’s face is occluded and occupies about one two-hundredth of the picture. His soul is not on view.

John Feitelson, a property investor and art collector, bought a couple of big drawings by Harding in the early 1990s and proceeded to commission a portrait from Harding through his dealer, Rex Irwin. At the time, Feitelson and his family were living in a pocket mansion created by the architect F Glynn Gilling in the first half of the twentieth century. By the time Harding came to the house to start work on the portrait, Feitelson’s wife Roslyn had been diagnosed with cancer. Harding set down some drawings and went away to complete the portrait in the studio. She did not live to see it. The empty green chair is symbolic of her; but in addition, Feitelson asked the artist to add a photograph of Roslyn and their twin daughters to the objects on the low table. When he sold the Gilling house, the portrait went into storage. Looking at it after some years, Feitelson was struck by the eloquence with which it evoked that time and place.

Feitelson appears very much alone in his magnificent reception room. In ranks before him, his art pieces seem like a defensive bulwark, and the sheer accumulation of paint in the picture contributes to the inaccessibility of his small figure. Feitelson particularly likes the way Harding captured the old glass in the French windows of his home, which, he remembers, had a refractive, slightly distorting character. To achieve the effect of light coming through the uneven panes, Harding went all-out with colour. By way of the greens in the window arches and the violet on the walls he created an atmosphere like that of a submarine cave, with wavering, muted light seeping in. We look ‘through’ the right hand window at a tree trunk and a piece of white concrete balustrade, a feature right at home in one of Gilling’s distinctively eclectic, Hollywood-Spanish-style architectural follies.